Annika Sippel, The Sāmoan Manumea – how can museums help to protect this national treasure?, Te Papa Blog, 15 July 2024

The Manumea, or tooth-billed pigeon (Didunculus strigirostris), is an endemic bird of Sāmoa, currently on the brink of extinction. How can museums help to protect this national treasure? In this blog, Research Assistant Annika Sung examines how Te Papa’s collections can teach us about the Manumea and its entwined relationship to various aspects of Sāmoan life and culture.

The Manumea: Sāmoa’s national bird

The critically endangered Manumea can only be found on the islands of Sāmoa, though it is estimated that less than 200 birds remain in the wild today. Its population has been significantly decreased through habitat loss (caused by climate change as well as human activity), the introduction of pests and accidental killing during pigeon hunting. Yet while it may be difficult to find a Manumea in the forests, it can easily be found in the history, language and culture of Sāmoa.

For example, ufiufi manu gase (“to cover up dead birds”) is a muāgagana, or Sāmoan proverb, which likens the nature of pigeons, like the Manumea, to cover the body of their fallen mate with their wings to someone protecting a friend or family member. The Manumea’s face is also represented on the local currency and can be seen on large-scale murals across Sāmoa, such as the one painted by Charles and Janine Williams as part of the ‘Save the Manumea’ campaign launched in 2019.

For museums too, the Manumea is more than a bird; it bridges the nature/culture divide imposed on museum collections by Western, scientific mindsets that utilise classifications such as ‘natural specimen’ or ‘cultural object’. In fact, we can find the presence of the Manumea in many different areas of Te Papa’s collections; here are some examples

Egg (Birds collection)

This Manumea egg measures 45.0 mm x 29.0 mm, meaning it is smaller than a chicken’s egg. It was collected in Apia on 14 July 1919 and officially registered into the collection of the National Museum in 1979. That is all we know about it; except that it is also a particularly rare specimen.

It is the only known Manumea egg in a museum collection, making it essential for researchers trying to ensure the Manumea’s survival by learning more about it. Manumea supposedly lay an egg only once a year, most likely low to the ground, making them extremely vulnerable to predators like cats and rats, which means finding an egg in the wild is near impossible.

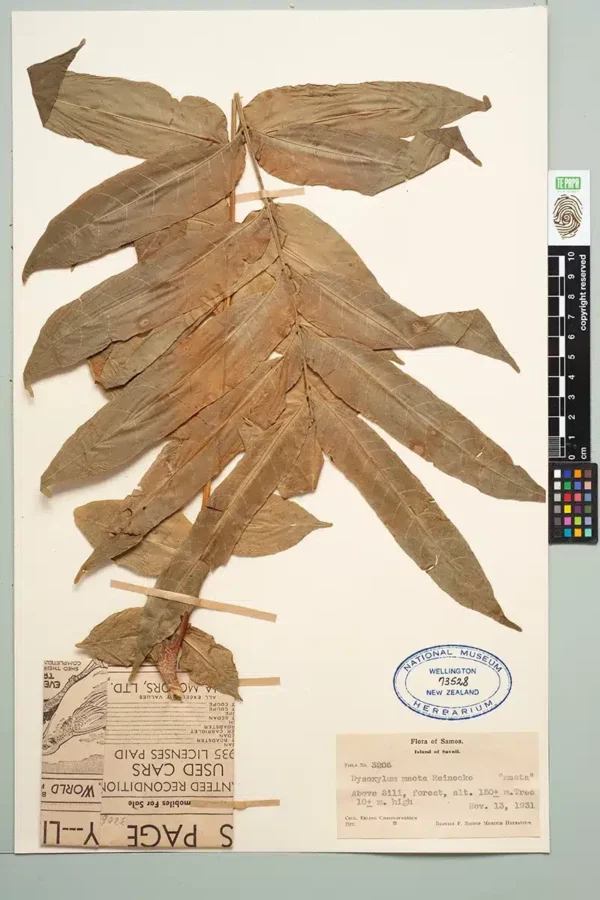

Maota (Botany collection)

Maota (Dysoxylum maota) is an indigenous tree of Sāmoa, boasting big, yellow fruits. D. maota is one of three species of Maota found in Sāmoa where two of them, Dysoxylum maota and Dysoxylum samoensis, are commonly found in lowland forest below 800 meters and are more favourable for Manumea, whereas the Dysoxylum huntii is an upland species common above 800 meters.

Manumea play a valuable ecological role as seed dispensers, seeing that due to their size and strong, toothed beaks they are the only birds able to feed on these fruit trees. This allows them to naturally restore native forests. The continued survival of this plant, therefore, is directly reliant on the survival of the Manumea, which is why locals in ‘Manumea Friendly Villages’, like Falease‘ela, Uafato, Falealupo and others, have started to rehabilitate the bird’s natural habitat by actively planting more Maota trees.

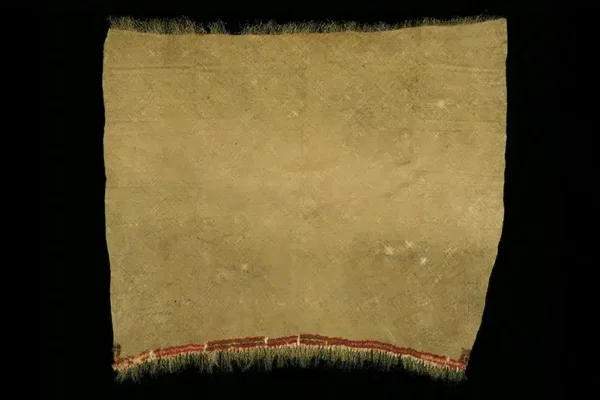

‘ie tōga (Pacific Cultures collection)

‘ie tōga (fine mats) are the most precious type of mat in Sāmoa and are generally considered the most valuable possession of Sāmoan families and traditions. They are exchanged and presented at weddings and funerals, and at other special occasions.

These mats also act as a reminder that in the past locals used to hunt and eat Manumea – again, only on special occasions, and they could only be consumed by high-ranking individuals. Their red feathers could subsequently be used to decorate the fringe of ‘ie toga, though nowadays makers primarily use dyed chicken feathers. Even though this practice of using Manumea feathers is now illegal, accidental killing during pigeon-hunting is still one of the biggest dangers to the remaining Manumea population today.

Patch: Bungaswehr (Art collection)

Patch: Bungaswehr is a contemporary artwork by New Zealand-born Sāmoan (Vaimoso/Siumu/Fasito‘otai) artist Leafa Wilson (aka Olga Krause). In view of her own German heritage, Wilson addresses the German-Samoan colonial legacy in this work, through bird imagery and text. She combines the German word ‘Bundeswehr’ (the armed forces) with the English colloquial word ‘bunga’, a racist term for people of colour, especially Pacific Islanders.

The Bundesadler, or German eagle, sits prominently and proudly in the centre, yet underneath it we see the word ‘Manumea’ boldly written in red, followed by a stylised bird’s head. The Manumea thus becomes part of a politically charged discourse on national identity.

Stamp (Philatelic collection)

This 1952 stamp from ‘Western Samoa’ (which is what Sāmoa was officially called during the New Zealand Administration period before gaining Independence in 1962) is part of a set of ten stamps with illustrations around the theme of ‘Village life’, depicting activities like making siapo, harvesting of cacao, fishing, preparing copra, and constructing a fale.

The Manumea is the only animal represented in this series, demonstrating how important it was for the daily lives of Sāmoans – it was as much part of the cultural heritage as anything manmade. And just like these stamps once circulated the image of the Manumea around the world, so we need to remind the world now about this unique and endangered bird, so that its cultural significance can continue to be recognised and grow.

Fa‘afetai tele lava to Moeumu Uili and James Atherton from Sosaiete Fa‘asao o Samoa (Samoa Conservation Society) for their continued efforts to raise awareness and protect the Manumea, and for their support of this blog.

Further reading

- Moeumu Uili, ‘Finding a Needle in a Haystack: Saving the Manumea’, Ubuntu Magazine 8, 2024, 64–77, https://issuu.com/ubuntumagazine/docs/ubuntu_magazine_e8_winter_2024?fr=xKAE9_zU1NQ

- MNRE and SCS, Save the Manumea. A National Campaign Strategy, Samoa Conservation Society and Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, Apia, 2019, https://www.savethemanumea.com/_files/ugd/fce189_c4255e1a94514e8ebc34ffd369eb23e3.pdf

- MNRE and SCS, Recovery Plan for the Manumea or Toothbilled Pigeon (Didunculus strigirostris) 2020–2029, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, Government of Samoa and Samoa Conservation Society, Apia, 2020, https://www.savethemanumea.com/_files/ugd/fce189_4b276ee20e064b658b6bb9ae23c10c27.pdf

- Rebecca Bray and Leone Samu, ‘O le Manumea: Samoa’s Little Dodo Bird’, Auckland Museum Blog, 26 May 2020, https://www.aucklandmuseum.com/discover/stories/blog/2020/samoa-s-little-dodo-bird

- Sosaiete Fa‘asao o Samoa (Samoa Conservation Society) official website, https://samoaconservationsociety.wordpress.com/projects/protecting-the-manumea/