A 2011 file photo of a skull awaiting its return to its ancestral home in East Arnhem Land for ceremonial reburial after more than 60 years in the possession of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. Credit: Glenn Campbell.

Tony Moore, ‘Huge conflict of interest’: Australia’s museums still hold 10,500 First Nations remains, The Brisbane Times, 2 October 2021

More skulls, bones or other remains of First Nations people now lie in eight Australian museums today than in 2010, despite a three-decade Australian government program to return remains to their communities.

The museums now hold “around” 10,500 First Nations ancestral remains as part of the government’s Indigenous Repatriation Program.

Those eight museums today also hold 11,300 secret, sacred objects, according to details revealed by the government this week.

In 2010, those eight museums held 7581 ancestral remains and 11,372 sacred objects, according to numbers from the museums provided to long-serving Queensland Indigenous activist Bob Weatherall when he was working for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission.

ATSIC was established by former prime minister Bob Hawke in 1990 and abolished in 2005.

The museums involved in Australia’s indigenous repatriation program since 1990

- Australian Museum (Sydney)

- Museum and Art Gallery of Northern Territory

- Museums Victoria

- National Museum of Australia (Canberra)

- Queensland Museum

- South Australian Museum

- Tasmanian Museum and Gallery

- West Australian Museum

Since 1990 overall these museums have received 1618 First Australian ancestors from nine countries overseas.

They have returned 2710 First Australian ancestors and 2240 secret, sacred objects to custodians in their communities.

Source: Office of the Arts, Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications

Those documents were provided to Bob Weatherall when he was a member of the International Repatriation Advisory Committee, appointed by then-federal Indigenous affairs minister Jenny Macklin.

The federal Office of the Arts, which manages the Indigenous Repatriation Program, initially disputed the figures provided by Mr Weatherall until furnished with a copy and a link to ATSIC’s International Repatriation Advisory Committee.

It subsequently declined to comment further.

The large increase in ancestral remains at Australian museums – despite the Australian government’s Indigenous Repatriation Policy – simply frustrates Mr Weatherall.

“They should be emptying their cupboards, not filling them up,” he says.

“I think it shows repatriation should be under Aboriginal ownership and control, not under government authority or a government science body.

“I think there is a huge conflict of interest there, and it needs to be sorted out.”

It is now the formal policy of the Australian and Queensland governments to return the remains of First Nations people to their local communities, despite its complexities.

The Australian government says since 1990, 2710 First Australian ancestors and 2240 secret, sacred objects have been returned by the eight museums to their local communities.

In one example in May 2021 three spears taken by Captain James Cook and his crew in 1770 were returned to the Gweagal people in NSW. They had been located at Trinity College at the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology. The Gweagal Shield remains in the British Museum.

The Office of the Arts said the process of returning ancient remains “is sensitive, complex and may take some time”.

“The timetable for the return of ancestors with provenance to a community is usually determined by the museums in close consultation with the relevant traditional custodians,” a spokeswoman said.

“The number of ancestors returned each year varies. Each return is community led and the timing is informed by the communities’ wishes and in accordance with their cultural protocols.”

It said increases in holdings of ancestral remains had to be discussed with individual museums.

Two museums – that are among the eight supporting the Indigenous Repatriation Program – provided details from their Indigenous Remains collections.

Queensland Museum’s ancestral remains holdings have doubled since 2010.

On June 7, 2010, the Queensland Museum held 382 ancestral remains and 216 sacred, secret objects, according to documents on all museums provided by Mr Weatherall this week.

However, by September 2021, the Queensland Museum said it held 1288 ancestral remains and sacred objects, which included many items which had not previously been recorded.

A recent 12-month audit shows 809 ancestral remains – bones and skulls – and 479 sacred, secret objects.

A Queensland Museum spokeswoman said some communities asked the Queensland Museum to “hold” remains for them when they were returned from other museums.

“They are held for communities. They are not on exhibition.”

Most recently Queensland Museum returned Burnett Rock engravings to the Bundaberg region; and ancestral remains to Malanda, in far north Queensland.

The Queensland figures were reflected in September 2021 data provided by the Indigenous Repatriation Program run by the federal Office of the Arts.

That data, made public last Thursday, showed that in Canberra, a similar story emerged at the National Museum of Australia.

In June 2010, there were 1346 ancestral remains at the National Museum of Australia, according to information provided by the museums to Mr Weatherall in 2010.

However, in September 2021, there are 2738 individually numbered sets of ancestral remains, the museum said.

“These represent a minimum of 463 individuals,” the National Museum said.

It holds 49 sets of remains at the request of Indigenous communities.

“The Museum has returned the remains of over 1200 individuals and 350 secret sacred objects to communities,” a spokeswoman said.

The Indigenous Repatriation Program estimates about 30 per cent of these ancestors do not have “provenance”, which means they cannot be linked to a specific community or place.

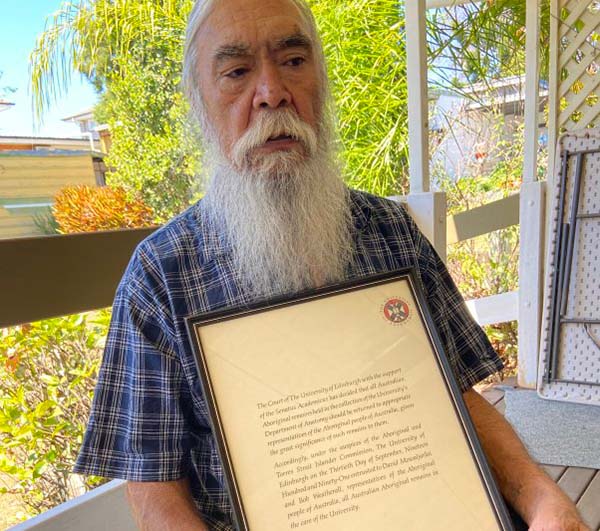

Mr Weatherall shakes his head slowly as I show him the 2021 figures from museums at his timber, suburban home in Brisbane’s northside.

He had a week earlier insisted that anywhere “between 7000 and 10,000 ancestral remains” were still held by the eight Australian museums.

The figures from the museum in the Indigenous Repatriation Program suggests he is correct.

His fight to have Indigenous remains returned to their communities, goes back four decades and was recognised this month at the Brisbane Festival.

The Brisbane Festival honoured his work in bring ancestral remains home in the stage musical Restless Dream, a collaboration with Queensland band, Halfway.

During one song Bloodlines No.2 Mr Weatherall sings in spoken verse: “We tell them who we are and where we come from. We are Kamilaroi, bloodline descendants from the Balonne, Moonie, Culgoa, the McIntyre and Barwon rivers.

“We’ve come to get you. We’ve come to take you home.”

Mr Weatherall has lost faith with the museum repatriation program and suggests change.

There needs to be a separation of the role of museums and the role of returning ancestors to their communities, he believes.

“It needs to be a Centre of Excellence for the repatriation of ancestors to get them all home, and it needs to be under the control of Aboriginal people.”

Mr Weatherall has a proudly framed statement from the University of Edinburgh Senate dated September 30, 1991, which names him as an appropriate representative to receive “all Aboriginal remains held by the university.”

Almost 600 ancestral remains and objects subsequently came home.

He set up a pilot project between 2011-12 to remove 32 ancestral remains from the Queensland Museum, the University of Queensland’s anatomy department and Queensland Police Forensics laboratories and had them reburied at the Kamilaroi burial grounds in St George.