Platypus diplomacy: students uncover hidden history, The University of Sydney, 17 July 2025

Winston Churchill, a German submarine and a platypus’ untimely demise: students delve into museum archives to solve a monotreme mystery.

Students from the University of Sydney have delved into the Australian Museum’s collection to solve an 82-year-old mystery surrounding the death of a platypus named Winston.

The unfortunate monotreme was named after British Prime Minister Winston Churchill who in 1943, as World War II raged, asked Australia for a platypus. (Churchill collected exotic animals, which he kept at London Zoo.)

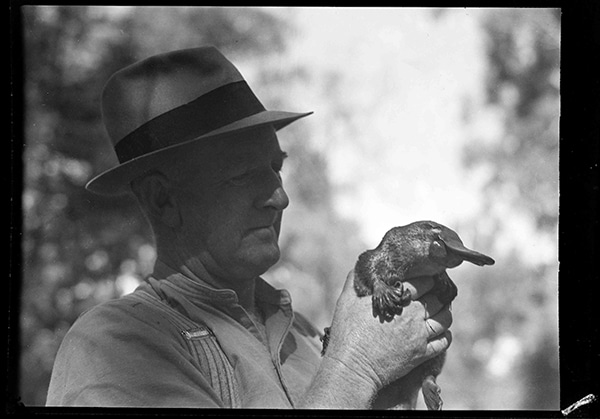

The Australian government recruited renowned naturalist David Fleay to catch a platypus (“truly a little beauty”, Fleay later wrote) and construct a “platypusary” for the five-week sea voyage.

Winston the platypus never made it to meet his namesake. On 4 November 1943, two days before the ship reached England, the ship’s logbook documenting his journey ends abruptly with the words: “Platypus found dead in water.”

A historical whodunnit

Media reports at the time said Winston died of shell shock after a German submarine blast. The students’ research into Fleay’s personal collections – a bequest to the Australian Museum – reveal this may have been a cover-up.

The logbook – part of Fleay’s bequest – includes meticulous records of the temperature on board the ship.

“We found very good evidence to suggest Winston died of heat stress due to high temperatures as the ship travelled through the Panama Canal,” said Paul Zaki, a third-year Bachelor of Psychology student. “It’s somehow even sadder than death by submarine detonation. But it feels pretty incredible that we were able to solve a historical whodunnit.”

Zaki, 22, is one of 12 University of Sydney students who became the first people to examine Fleay’s collections. The project was part of a collaboration between the University and the Australian Museum, allowing students in the School of History and Philosophy of Science to examine archival material.

“It’s a hands-on internship that gives students a behind-the-scenes perspective that helps them understand museums as part of the history of Australian science.”

Dr Daniela Helbig, Faculty of Science

Behind the scenes at the Australian Museum

The group spent several weeks at the museum last year, labelling, describing and digitising objects from Fleay’s collections, including logbooks, platypusary blueprints, photographs and fragile glass slides designed to be inserted into a “magic lantern” – the predecessor of the slide projector. The students collated their findings into a publicly accessible online record that sheds light on Fleay’s life’s work and the history of “platypus diplomacy”, which saw Australian wildlife sent overseas to stimulate international goodwill.

“This is quite a special opportunity for our students,” said Dr Daniela Helbig, a senior lecturer in the School of History and Philosophy of Science, who co-taught the unit of study with PhD student, Rebecca Mann. “It’s a hands-on internship that gives them industry experience, a chance to work with fascinating archival material, and a behind-the-scenes perspective that helps them understand museums as part of the history of Australian science.”

David Fleay: a pioneering conservationist

Fleay died in 1993 and his personal collections remained with his family until their arrival at the museum last year. The material documents Fleay’s pioneering conservation work. He was the first person to breed the platypus in captivity, and showcased Australian animals at home and abroad. In 1952, he established the David Fleay Wildlife Park on the Gold Coast, which remains in operation.

Dr Vanessa Finney, the Australian Museum’s Head of Archives and Library, said the students worked hard to understand the collection, bringing it to life for online audiences.

“They loved the riddle of the platypus death at sea, and piecing together images, diaries and newspapers to solve a mystery and create innovative visual narratives,” Dr Finney said.

“Hopefully they gained some skills and want to work further with collection care, visual storytelling in archival collections and museum histories.”

New opportunities for students

Next semester a new group of students will explore another recently acquired museum collection – the archives of Australian ornithologist and nature photographer, Les Chandler (1888-1980).

Next semester a new group of students will explore another recently acquired museum collection – the archives of Australian ornithologist and nature photographer, Les Chandler (1888-1980).

The museum plans to undertake further conservation and digitisation of the Fleay collections.

Volunteer citizen scientists can get involved in digitising the museum’s collections through the DigiVol project.