Our distinctive fauna find a second life in the Australian Museum, now closed for renovations until mid-2020. Credit: Jonathan Cami.

Jonathan Cami, Amid skin and bone and the scent of offal, a boyhood dream is realised, 14 September 2019

In the depths of the Australian Museum a “sorcerer” casts his spell and a photographer’s long-held fascination with taxidermy comes full circle.

One of my childhood memories is of a squirrel in our freezer. It “lived” at my parents’ house in Barcelona for many years. It was a beautiful Eurasian red squirrel, with pointy ears and a big furry tail. My father had found it by the side of the road while he was driving through a forest in the Pyrenees. It was already dead, likely hit by a car. My old man decided to preserve it until he found time to take it to the local taxidermist.

In my seven-year-old mind, the taxidermist would be a sage man, possessing an ancient, obscure knowledge. His small, smoky laboratory would be filled with Erlenmeyer flasks, test tubes and glass funnels. He would be gifted enough to transform this little dead rodent into a sculpture, so beautiful it would have to be placed in a prominent position in our home. On a bookshelf up high, perhaps, next to the old books, the ones the children aren’t allowed to touch.

Sadly, the little neighbourhood taxidermist shop closed not long after the squirrel arrived, so my curiosity about the man and his shop was never satisfied. But after many years, and moving across the globe to Sydney, the little boy in me finally got to enter that magical shop. Well, not that one exactly.

As a freelance photographer, I’m lucky to have plenty of time on my hands, which is important as I’m the main carer for my two children. We live near the Australian Museum and decided to become members. We love the Search & Discover Room, where the little ones can touch the stuffed animals and ask anything that comes into their heads. It’s a place, crucially, where I can set my supervision level to “relaxed mode” for a couple of hours.

A little bored of the same routine after months of weekly visits, I began taking portraits of the animals, while my kids were looking for stick insect eggs or hiding under the big turtle shell. My little boy liked to hug the resident wombat, so I thought it would be beautiful to take a portrait of it. The outcome wasn’t what I had in mind, but it lit a creative spark. At this point the photographer overtook the father; now I wanted a whole series of Australian animals for my portfolio. The little boy from Barcelona rose up again from inside me. I wanted to meet the museum’s taxidermist, Mr Wang, to see if his laboratory looked as I’d envisaged one all those years ago.

A young woman from the museum accompanied me downstairs to Mr Wang’s basement lab. The unforgettably dense scent was a mixture of old and dead. Strangely, it brought back memories of my weekly visits to La Boqueria, a fresh food market in Barcelona – more specifically, the offal aisle, where my father used to buy his tripe. The lab wasn’t dark and mysterious; there was no smoke, no flasks lying around. But it was still a magical place, filled with strange tools and plenty of stuffed animals, skins and bones.

My eyes fell on the remains of an echidna in a tub. Its flattened skin, still fresh, was attached to a board, its spikes pointing towards the ceiling. Next to it was a particularly big, rusty mezzaluna (a two-handled, curve-bladed knife). Mr Wang was in the midst of preparing a little bird to be stuffed, his bare hands inside it. It was too gory for my young female companion, who made a quick excuse and fled upstairs.

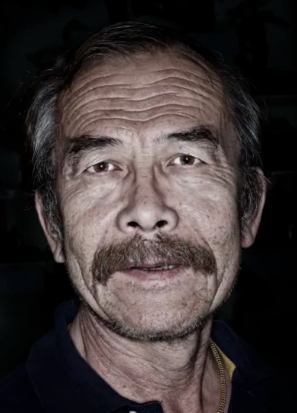

Mr Wang (pictured above right) looked exactly as that little boy in Barcelona imagined, a sorcerer with Kublai Khan looks, gold teeth, a moustache and grey hair, able to transform roadkill into magical creatures. I tried to strike up a conversation, but my strong Catalan accent was too strange for Mr Wang. English is not a first language for either of us, our respective cultures too far away to establish an unbroken conversation. He seemed genuinely puzzled, didn’t understand why somebody would be interested in him. In those 10 long, quiet minutes the only word he used was “yes”, eager to get back to emptying that little bird. The hair on the back of my neck stood up when we shook hands goodbye, Mr Wang offering the bare hand he’d just been working with.

All I really know about Mr Wang is that he’s been with the museum for decades, after immigrating from Mongolia a long time ago. The child inside me likes to imagine he used to wear a loovuuz and sleep in a yurt. That he rode horses across the Mongolian steppe and hunted antelopes with a bow. And that his elders taught him how to preserve the furs and skins of beavers and marmots. But it probably never happened this way.

The Australian Museum is now closed for renovations until mid-2020. My kids are growing up way too fast, and the Search & Discover Room will be too small for them very soon. And, although I’ve tried, I don’t believe I’ll ever know if the elusive Mr Wang once wandered through the Gobi Desert. But in his presence I finally closed the circle, connecting the sorcerer of my childhood dreams with the stuffed animals of my children’s.

So what happened to the squirrel? After many years in the freezer, hiding behind bags of frozen peas and containers of soup, my mum decided to apply some common sense – and put it in the bin.