Australian workers join the boycott by carrying out demonstrations on the streets, spraying graffiti on walls to support Indonesian independence. (Courtesy of Noel Butlin Archives Centre/Australian National University).

Alex Dalziel, 75 years of ‘Black Armada’: Australian dockworkers defend Indonesia’s independence in 1945, The Jakarta Post, 9 September 2020

On Sept. 23, 1945, dockworkers in Australia refused to work on Dutch vessels in support of Indonesia’s Independence, a little-known historical fact that was the beginning of the Indonesia-Australia relationship.

It was a fragile time for the nascent nation, weeks after the proclamation of independence on Aug. 17. News about the proclamation spread via telegraph and also reached the ears of the Netherlands East Indies (NEI) government-in-exile, based at Camp Columbia in Wacol, Brisbane, Australia.

Although unable to defend their colonial holdings against the Japanese in World War II, the NEI government sought to reclaim their oil and rubber-rich former colony with assistance from the allied powers.

This coalesced into “police actions” undertaken by the NEI government in an attempt to recolonize Indonesia and the eventual armed conflict that characterized the early years of the Indonesian republic.

However, workers manning the ports of cities like Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Fremantle sought to protect Indonesia’s newly found independence in a series of “black bans” against Dutch vessels headed to recapture their former colony.

The Dutch vessels stopped from leaving Australian ports from 1945 to 1949 are known as the Black Armada.

Call to arms

Radio Bandung was the first to broadcast Indonesia’s independence proclamation speech in English via short-wave radio and was heard loudly by those in the United States, China, India and Malaysia. For wharf workers in Australia, it was a call to arms.

For a broad section of the international left and former colonial countries, the proclamation of independence was the catalyst for an international movement of anticolonial struggle — one that united the people of Indonesia, Australia, India and China in a fraternity unreplicated since its time.

The internationalism at the heart of the Black Armada campaign and Indonesian independence is something often overlooked by Indonesians and Australians alike.

Melbourne-based Ariel Heryanto, an emeritus professor at Monash University and director at the university’s Herb Feith Indonesian Engagement Center, said the black ban campaign was one of many instances of international support for Indonesian independence.

“The achievement [independence] was possible thanks to international support, especially from Australia. The Black Armada was the pioneer but not the only instance of Australia-based continued support,” he said.

During the early years of Indonesian independence, the two countries connected in a way that has often been forgotten due to the rocky and complicated decades of international relations that followed.

Prior to the 1940s, there was little public exposure between Indonesians and Australians.

Seamen at the forefront

World War II brought many foreign sea workers to Australia, among them Indonesians who manned Dutch ships. Many Indonesian political prisoners were also brought by the Dutch and freed due to Australian government intervention — at a time when the racist white Australia policy was still in effect.

In Sydney, members of the Indonesian Seamen’s Union were following the events back in Java via radio. The proclamation sprung these workers into action and from the distant shores of Australia, they sought to protect their country’s independence.

This started in September 1945 with Indonesian workers boycotting four Dutch ships in Sydney alleged to be carrying arms and ammunition for the suppression of Indonesian independence.

The Union sought assistance in this fight from the Australian Waterside Workers Federation (WWF), who as the result of the post-war influx in union membership, exercised a lot of influence over Australia’s wharves.

Their message resonated with the trade unionists, who believed that the Dutch return to Indonesia was in violation of the 1941 Atlantic Charter. The peace pact focused on territorial rights, freedom of self-determination, economic issues, disarmament and ethical goals, including freedom of the seas and a determination to work for “a world free of want and fear”.

Consequently, in September 1945, the WWF placed a “black ban” on outgoing Dutch ships bound for Indonesia, intending that no arms would be shipped to suppress Indonesian independence.

Maritime connection

By its very nature, maritime work is an international profession, forging ties between otherwise insular nations.

Indonesian composer and pianist Ananda Sukarlan has worked with Aboriginal Australian artists on his orchestral work The Voyage to Marege. Sukarlan said there had been connections between the Bugis seafarers of South Sulawesi and the Aboriginals in northern Australia for centuries.

“There are similarities in their languages and folktales,” he said.

This maritime connection between the two countries endured into the 20th century and was the link that brought the Indonesian independence struggle to Australia.

In October 1945, the Dutch ship SS Van Heutsz was grounded at Dalgety’s Wharf, Brisbane, as Australian dockworkers refused to load arms and ammunition in the ship bound toward Java.

In Melbourne, the SS Karasik — a ship formerly commandeered by the allies for the war effort — was also held up as a result of the black ban on Dutch ships. It is estimated by labor historian Rupert Lockwood that the campaign grounded 559 ships headed to Indonesia as part of the Dutch reclamation effort.

By late 1945, trade union documents show the Dutch boycott had extended to many Australian labor unions, like the Australian Council of Trade Unions, the Railways Union and the Seamen’s Union of Australia.

From docks to streets

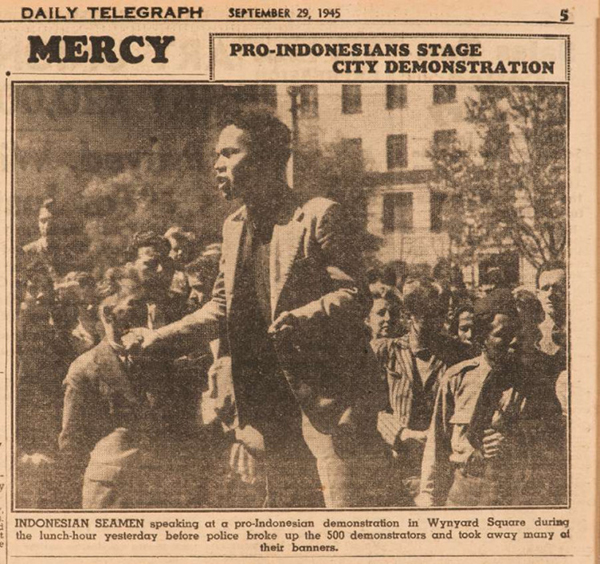

In addition to job stoppages, the workers carried out demonstrations on the streets. Photos from the time show graffiti scrawled on walls reading “Dutch profits or Java’s freedom?”, “Diggers support Indonesians”, and “Down with Dutch imperialism”.

“Diggers” refer to the term for private soldiers from Australia and New Zealand but later used to display egalitarian relationships or “mateship”.

The black armada campaign is best illustrated in the 1946 documentary film Indonesia Calling directed by Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivans. The film recreates major scenes from the protests, showing the real Indonesian workers and intellectuals who were present at the event.

To celebrate Indonesian independence, the Australian National Maritime Museum launched on Aug. 26 the online exhibition Two Nations: A Friendship is Born — Australia and Indonesia 1945-49, which reveals personal stories and archival material that explores the neighboring country’s role during Indonesia’s independence struggle.

The black armada movement was a unique point in Asia Pacific history where it seemed the people of Indonesia, Australia and several other Asian countries fought in a shared struggle.

75 years later

In the 75 years between then and now, politics has often fractured the region.

For Heryanto, Indonesia’s 75th anniversary of Independence is a moment to pause and reflect on the diverse nature of the Indonesian independence struggle and Indonesian independence itself.

“It is sad to see how inward-looking so many nations have become these days. How narrow-minded and exclusionary the idea of nationhood, national identity and national interests have become. Today’s Indonesia is no exception,” he said.

“From the very beginning, the Republic of Indonesia has always been a product of global flows of peoples of different races, of ideas and tools for living. These facts are now mostly overlooked or denied in the current public obsession with a nativist fantasy of ‘purity’ and ‘authenticity’.”

See also: https://www.sea.museum/two-nations