Eda Tang0, Auckland Museum wharenui conservation a process of whakatika or putting things right, Stuff, 23 April 2022

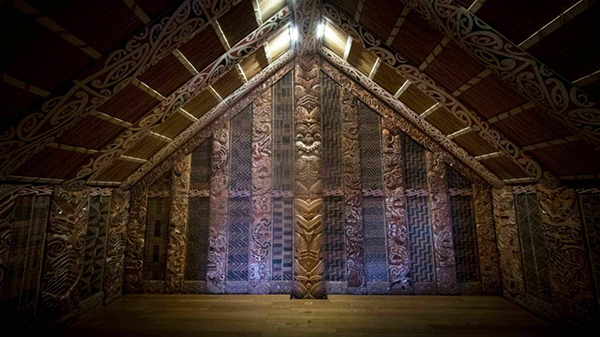

Crossing the paepae (wharenui threshold) and entering Hotunui is “almost existential” for Paul Majurey of Ngāti Maru/Marutūāhu.

“It’s very reaffirming of identity … it’s a very physical and metaphysical connection to our past and the richness of the narratives and all the histories.”

Hotunui is an iconic taonga of Ngāti Maru and all the Marutūāhu tribes, embodying the spiritual presence of the ancestors and tribal histories.

Taking three years to build, Hotunui stood in Pārāwai (now Thames) from 1878. The whare rūnanga (meeting house), named after the founding ancestor of the Marutūāhu, was the centre of sacred rites, tangihanga and rūnanga hui.

Majurey, the kaitiaki of Hotunui, describes it as an “embodiment of our culture, the knowledge ecosystem” and a “home of mātauranga”.

By the 1920s it was in a state of deterioration as the people of Hotunui had been removed from their land by raupatu and predatory Crown land practices. Ngāti Maru leaders were approached by the Auckland Museum in 1925 to house Hotunui on loan.

A primary factor in the decision to transfer Hotunui to Tāmaki Makaurau was the location of the new Auckland Museum at Pukekawa Maunga (Auckland Domain) given the long-standing relationships of Ngāti Maru and Marutūāhu with Pukekawa. Hotunui was dismantled and shipped to Auckland for storage before being re-erected for the Auckland War Memorial’s official opening in 1929. The whare rūnanga has stood there ever since.

Majurey says the old people hope the whare enables manuhiri (guests) to “appreciate what our people have contributed in terms of the culture and enrichment of art and customary knowledge”. Hotunui is the most visited whare in the world, says Majurey, and the only one many manuhiri ever enter.

Heidi Brickell (Ngāti Apakura, Ngāti Kahungunu), learning specialist at the museum, delivers a mātauranga Māori programme to tamariki. “It always amazes me how much a lot of our country has missed out in learning about mātauranga Māori,” she says, “and they’re often really surprised at how complex it is.

“Hotunui is a whare that exemplifies a lot of the creativity and the technological shifts around a time early on, in the process of colonisation.”

The whakairo (carvings) are distinctively coloured with orange and black paint, as opposed to traditional red paint or dye. Its use of native timbers, carvings, kōwhaiwhai (painted scroll ornamentation) and tukutuku (ornamental lattice work) panels comprise the ecosystem that Hotunui represents.

Majurey says, “I think this is a reflection of taha Māori: a very adaptable people seeing multicoloured enamel paints, having access to metal chisels, and being able to apply the craft and mastery of the art form into what you see here, which was somewhat radical and controversial at the time.”

Hotunui was the result of the hononga (union) between Ngāti Maru and Ngāti Awa, including the marriage of Mereana Mokomoko (daughter of Ngāti Awa rangatira Apanui Hamaiwaho) to Hauāuru Tīkapa (Wirope Hotereni) Taipari, son of Te Hotereni Taipari. The whare is on long-term loan to the museum by the Taipari whānau and Ngāti Maru. It is still used by them today for traditional rites, hui and wānanga.

It’s a “very meaningful, ongoing relationship with descendants that we cherish,” said Nigel Borell, curator taonga Māori (Pirirākau, Ngāiterangi, Ngāti Ranginui, Te Whakatōhea).

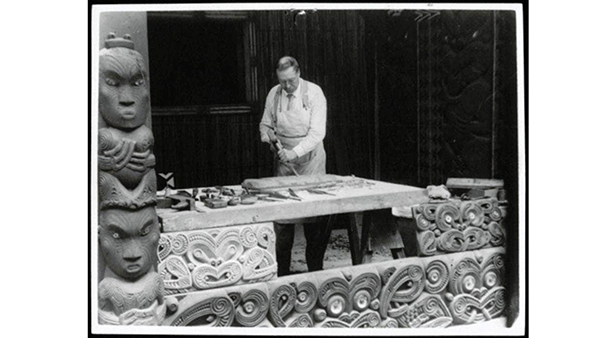

Upon its arrival, the museum commissioned Thomas Chappe Hall, an Englishman who had learnt to carve from a Māori leader, to carve an alternative base for the whare. These carvings can be easily identified at the bottom of the panels where they aren’t painted in the polychromatic scheme. However, not everything that happened at the time was above board.

When the museum’s acquisition of the whare happened, the terms and conditions said that it would have a thatched roof on the inside and outside. The polychromatic carvings were also concealed with a coat of “museum red” paint.

Vasiti Palavi (Te Rarawa, Ngāti Kuia) is the current head of collection care. She thinks these past actions were done to present the whare in a pre-colonial manner, “when actually, Māori were adapting constantly and using lots of different materials”.

While conducting a conservation report in the 1980s, conservators realised that, originally, Hotunui had a corrugated iron roof. The reinstatement of the corrugated roof then became part of the conservation project.

“They didn’t go to a hardware store and get corrugated iron … They actually went and got a piece of steel that was the same colour and aged it,” Palavi says. “They also put the corrugations in to match what they saw in the photos.”

Palavi says it’s about conserving to ensure that there is stability and a whole whakatika (rectifying) process to get things back to how they were. “It’s really honouring Hotunui and restoring the things that have been done wrong in the past.”

According to Palavi, the current assembly of the wharenui is close to the original to the best of their knowledge.

“As part of our duty of care, Ngāti Maru and the whānau and descendants are always involved.” Whether it is cleaning, maintenance or interventive work, it all goes through the whānau, and they are notified before any work is undertaken.

All the efforts over the years since 1985 are a “physical and metaphorical restoration for the mana of Hotunui”.

The whare was painted red twice covering the innovative polychromatic scheme. Only in 1981, it was recognised that the colour was inaccurate and paint restorations began.

The painting of taonga Māori with a recognisable kōkōwai (red ochre) colour “was a really colonising thing, particularly in museums where they wanted to keep Māori culture static”, said Brickell.

Following the 1985 report, kaimahi (workers) were brought on to go through all the pou and remove those two layers of paint.

He Korahi Māori manager Nicola Railton (Ngāti Kuri, Ngāpuhi) said that the removal of the red paint “revealed the visual beauty of Hotunui … but at the same time, metaphorically, the removal of the red paint seems to have revealed all these layers in Hotunui’s trajectory and some of the adaptations that the museum has made to the taonga and reconnected whānau to those histories.”

“While we had no knowledge of that taking place, what’s been important in that relationship has been the willingness to understand, to learn, and to make right” said Majurey. The ability to “go forward in a progressive and positive way, really is a feature of that relationship”.

“Museum practice has shifted so much from that era,” said Railton. These narratives have meant that contemporary taonga are included in galleries too.

A living taonga

Brickell witnesses visitors of all ages interacting with the whare rūnanga: placing their palms on the whakairo, meditating, and gazing overhead at the tīpuna (ancestors) represented in the carvings.

“It is quite sad for me when taonga are kept behind glass because it is an intrinsically Māori way of interacting with things with your body,” says Brickell. “It’s a living taonga.”

Says conservator Palavi: “It’s balancing that risk [of wear and tear] as well as having those opportunities for whānau who may whakapapa to it or other people who […] know it as a place to connect with something that has such high mana and be within the mauri [life force] and wairua [spirit] of it.”

The whare is used to welcome visitors and introduce them to Māori tikanga. Often protocols such as mihimihi or pōwhiri taking place at the whare rūnanga are experienced by the wider public.

“I think that’s healthy that our public get to see the meeting house being used in its original capacity as a living, functioning, cultural experience item,” Borell says.