Postcard of “On the first Lunar cosmodrome” (1968), by Andrey Sokolov and Alexei Leonov (courtesy Moscow Design Museum).

Alison Meier, A History of Science Fiction’s Future Visions, Hyperallergic, 31 July 2017

The Barbican Centre’s Into the Unknown explores science fiction as a cultural force, and how it channels our most optimistic and dystopian projections about the future.

LONDON — The 1982 film Blade Runner imagined 2019 Los Angeles as a dystopia of noirish neon and replicants, robots sent to do hard labor on off-world colonies. It’s a future in which engineered beings are so close to humans as to make the characters question the very nature of life. We’re now just a couple of years from this movie’s timeline, and although our robots are still far from mirroring humanity, our science fiction continues to envision giant leaps in technology that are often rooted in contemporary concerns of where our innovations are taking us.

Patrick Gyger, curator of Into the Unknown: A Journey through Science Fiction at the Barbican Centre, told Hyperallergic that, for him, science fiction “allows creators to look beyond the horizon of knowledge and play with concepts and situations.” The exhibition is a sprawling examination of the genre of science fiction going back to the 19th century, with over 800 works. These include film memorabilia, vintage books, original art, and even a kinetic sculpture in a lower-level space by Conrad Shawcross. “In Light of The Machine” has a huge, robotic arm twisting within a henge-like circle of perforated walls, so visitors can only glimpse its strange dance at first, before moving to the center and seeing that it holds one bright light at the end of its body.

Most of Into the Unknown is concentrated in the Barbican’s Curve space, a winding gallery with a high ceiling that permits objects to be stacked to the ceiling. They range from spacesuits worn in Star Trek and Moon (2009), to the robot TARS from Interstellar (2014) and Ava from Ex Machina (2015), to drawings by H. R. Giger for the Alien series and paintings by James Gurney for his Dinotopia books. The post-war architecture of the Barbican is a fitting setting for Into the Unknown, with its concrete angles and utopian spirit. In conjunction with the show, Penguin Classics released a series of limited-edition science fiction books with Barbican architecture on their covers. The brutalist conservatory graces H. G. Well’s The Island of Doctor Moreau, and two of the triangular towers appear on George Orwell’s 1984.

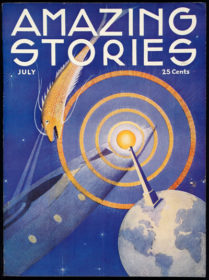

Throughout the exhibition, niche and popular culture are juxtaposed, chronicling how science fiction emerged as a cultural force in the 20th century. Manuscripts by Jules Verne hold incredible insights into how much research the author put into works such as Around the World in Eighty Days (1872), and an adjacent display of dinosaur models sculpted by Ray Harryhausen for 1960s stop-motion shows how, by the mid-20th century, films were using recent scientific knowledge for entertainment. Artwork like Dino De Laurentiis’s storyboard drawings for the Sandworm battle in the 1984 Dune (and some nearby concept art by Giger for Alejandro Jodorowsky’s unrealized version), testify to artists’ presence in shaping science fiction. An array of aerospace industry advertisements from the 1950s and ’60s feature fantastic spacecraft similar to those in Soviet postcards illustrated by Andrey Sokolov and Alexei Leonov (a cosmonaut who created the first artwork in space).

Gyger noted that the fact that the genre “has been so impactful” cannot be separated from the link to “its context of production and to the mass market that makes it flourish.” Over the years, this has involved pulp magazines, trading cards, comics, and paperbacks, often aimed at young audiences, or presented as a cheap thrills.

Certainly science fiction is incredibly popular at the moment — see the success of Westworld, The Handmaid’s Tale, and Black Mirror (which is featured in the exhibition through a six-foot video installation based on the unnerving virtual world in the episode “Fifteen Million Merits“). While these series explore serious issues in our reality, there’s still a tendency to overlook them as serious art (unless you count The Lord of the Rings, no science fiction film has won the “Best Picture” Oscar, for instance). Into the Unknown might not sway anyone without a curiosity for science fiction, being that you’re immediately immersed in a constellation of spaceships, dinosaurs, alien monsters, and robots. But for those with an interest, it demonstrates how these themes developed from “low” to “high” art.

The exhibition shows, but does not dwell on, who has been left out of a history mostly shaped by white men (there are rare exceptions on view, like the “Astro Black” video installation by Soda Jerk that muses on Sun Ra’s theories of Afrofuturism). It would be worthwhile to spend more time on figures who broke through these barriers, such as author Octavia Butler. As discussed on a recent podcast from Imaginary Worlds, her black characters were sometimes portrayed as white on her book covers to make them more appealing to science fiction readers. The exhibition could also have a deeper context for why certain veins of science fiction are prominent in particular eras, and perhaps question why we don’t have a lot of science fiction narratives on current crises like climate change. For instance, the much smaller 2016 exhibition Fantastic Worlds: Science and Fiction 1780–1910 from the Smithsonian Libraries compared milestones like Mary Shelley’s 1818 Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus with physician Luigi Galvani’s “animal electricity” experiments on animating dead frog legs, and highlighted how Jules Verne channeled the doomed Franklin expedition in his 1864 book The Adventures of Captain Hatteras.

Nevertheless, having an exhibition like Into the Unknown at a mainstream space like the Barbican is significant, showing the art world appreciates science fiction beyond kitsch. And science fiction continues to be one of our important portals for thinking about the ramifications of our technological choices, and where they might take us. There’s a reason that 1984 is now having a popular Broadway production in a year of “alternative facts,” and why Black Mirror episodes such as “Nosedive,” where a person’s worth is judged by their social media “likes,” resonate so deeply.

“It is the genre of ‘what if,’ shedding light on our hopes and fears for a future closely linked to our present and our environment,” Gyger said. “In doing so it inspires and warns us, while entertaining us, creating a plethora of iconography, and leaving a deep mark on culture.”