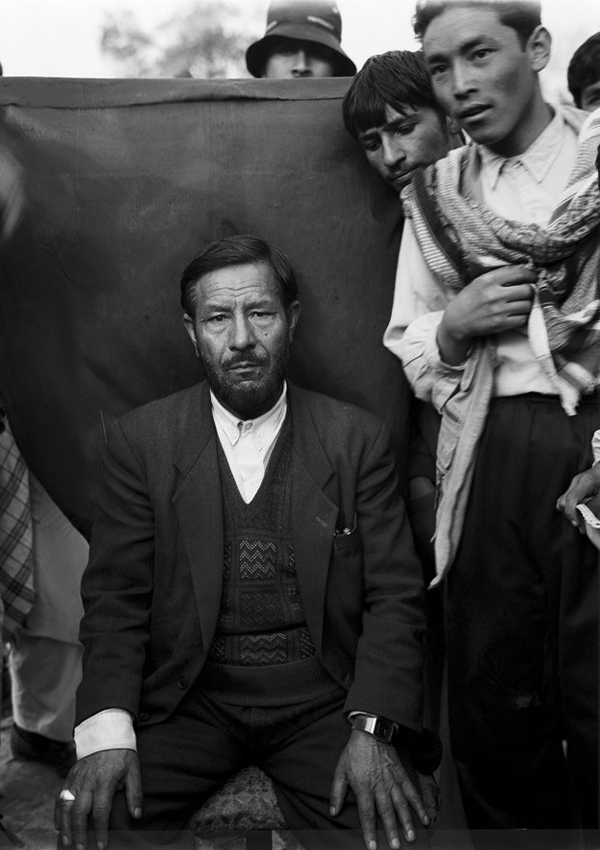

Tajik refugees, Saki Camp, northern Afghanistan, 1993. Credit: Stephen Dupont.

Stephen Dupont, ‘The beauty and tragedy of the place Afghans call home’: a photographer’s homage, The Sydney Morning Herald, 11 September 2021

Portraits of a war-battered country, from moments of high drama to the superhuman will to endure. Contains graphic content.

My first trip to Afghanistan was in the winter of 1993. I hid my camera gear in the car as we drove towards the capital, Kabul, avoiding militia roadblocks by driving fast and tossing thousands of Afghani banknotes out the windows, so the soldiers would chase the money and not shoot us. The country was in chaos, a legacy of its communist days and nine-year war with the Soviet Union. Different warring factions had divided the city into a serrated maze of frontlines and trenches.

I was bunkered down inside the main hospital. The wounded were arriving in droves, casualties of the shelling. There’s one photo I recall most, the one I chose not to take. I saw a gurney and a child underneath a sheet. I lifted the sheet and to my horror, saw no face except one eye. Momentarily turning around, I saw the child’s parents looking at me. I gently lay the sheet back over the body.

Over 20 years of travelling to Afghanistan, I always sought to tell the human stories of Afghans and the attempts by many brave Allied soldiers to build a better life for them after the Taliban tyranny.

In 2005, I was embedded with a US Army Psychological Operations Unit in Kandahar. After six weeks of missions with American soldiers, my flak jacket and helmet felt like part of my body as we rumbled out of Kandahar Airfield inside a packed Humvee. Above my head, AC/DC’s Hell’s Bells was blaring out of a loudspeaker; later it was Rage Against the Machine and even the Star Wars theme.

They played the music to annoy their enemy: “It’s the only way we can find the Taliban,” my psych-ops guide explained. “Otherwise you just don’t see them.” One marine described it to me: “It’s like chasing ghosts. These shadows pop out of caves and attack you, and then they drop their guns and run away.”

Two decades after the September 11 attacks, the ensuing US invasion, and the images of desperation and turmoil at Kabul airport as the heart-wrenching evacuations unfolded, I can’t offer any solution to the many problems facing Afghanistan. What I can offer is respect for the beauty and tragedy of the place Afghans call home.

Tajik refugees, Saki Camp, Northern Afghanistan, 1993

During this, my first trip to Afghanistan, I went to cover a refugee crisis in the north of the country. A civil war in neighbouring Tajikistan had forced tens of thousands to flee to safety, with the irony that safety meant living in arctic conditions in a desert of death. It was so cold that I could only take a few frames at a time before I had to stuff my hands deep inside my thermals again. Men were busy digging great big holes in the earth to cover with tents or small ones for the many dead. People huddled around fires cooking and offered me the little food they had. To say they’re hospitable to guests is an understatement.

I wandered across the dusty plains like a lost explorer, searching for images. The photograph I always go back to is of a wedding ceremony inside the camp. It was the only normal thing I saw that day, the only time I saw a smile and heard a laugh.

Northern Alliance soldier, Bagram, 1998

Covering the civil war between the Northern Alliance and the Taliban in late 1998, I met a soldier inside a bombed-out ruin along a frontline near Bagram Airfield, just north of the capital. It was his shell-shocked gaze that struck me first, but then I saw his prosthetic arms.

He told me his story, which encapsulates the absurdity of war: “I was not a soldier before. I used to work for an international non-government organisation trying to rid the country of landmines. One day I was de-mining when one blew off my arms – a mine planted by the Taliban. It was then that I decided to join the Northern Alliance and learnt to shoot an AK-47 with my new arms, so I could take my revenge.”

Northern Alliance soldier, Bagram, 1998. Credit: Stephen Dupont.

Anonymous portrait, Kabul, 2006

Of all the photographs I took in Afghanistan, one of my favourites is of this man in a dusty and busy Kabul bus station. Somehow the man’s solemn look and the various emotions from the crowd make the shot simultaneously timeless and present. Maybe he is the face of all Afghans: proud, strong and confident – but worried.

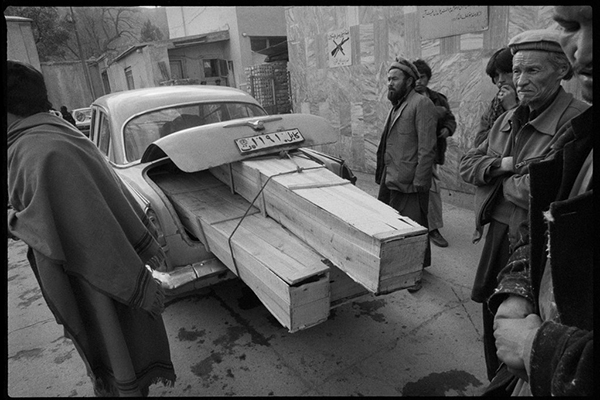

Taxi delivering coffins, Jamhuriat Hospital, Kabul, 1993

With chaos all around the hospital, coffins arrived in the boot of a taxi as the morgue filled up. The dead were mostly civilians caught up in the fighting across Kabul. On another occasion, a cab rolled on up through the hospital gates with a shredded and bloody leg dangling out of the boot.

Orphanage, Kabul, 1995

I was invited inside an orphanage for a photographic project about the children of Kabul and how they were affected by the war. Housed inside a Soviet-era apartment block on the outskirts of the city were hundreds of young war orphans. Walking inside one of the rooms, I came across this scene, which looked like a miniature Last Supper.

Taliban POWs, Yangi Qala district, Northern Afghanistan, 1998

Rather than condemn the Taliban prisoners to cells, the legendary Afghan warlord Ahmad Shah Massoud – whose Northern Alliance troops were at the time fighting the Taliban – had them work the fields and live in open compounds. He treated them more like compatriots than an enemy. Said Massoud: “We will not be a pawn in someone else’s game; we will always be Afghanistan!”

Wounded child, Gonbad village, Kandahar Province, 2005

A young boy is caressed by an elderly man whom I assume is his father. I’m drawn to the sad tragedy of the scene; the shaft of light that crosses the child’s face seems almost biblical to me.

The man says the Americans shot the boy; it’s impossible to know. It was the same day that I took photographs of US soldiers burning the bodies of two dead Taliban soldiers, which became international news and eventually led to changed US military policy. But it’s the picture of this child that I think about more – maybe because I’m a father, too. It’s a sad reality that innocent children too often become the victims of these adult war games.