The Museum of Science and Industry, pictured here in 2018, is an iconic fixture on Chicago’s South Side lakefront. (Brian Cassella/Chicago Tribune).

Steve Johnson, The Museum of Science and Industry is getting a new name after Chicago billionaire Ken Griffin donates $125 million, Chicago Tribune, 4 October 2019

The Museum of Science and Industry will rename itself after Chicago philanthropist Ken Griffin, who is making the largest donation in the institution’s history, the museum announced Thursday.

The sprawling science, tech and business museum on the city’s South Side will become the Kenneth C. Griffin Museum of Science and Industry after the museum’s board voted to accept Griffin’s $125 million donation and the name change Thursday morning.

It’s a major change in the Chicago cultural landscape, prompted by one of the largest cash donations ever to a local cultural institution. Griffin, founder of the hedge fund Citadel, has been one of the most prominent and active donors to cultural and educational organizations through his Kenneth C. Griffin Charitable Fund, with giving that now with the MSI gift totals over $1 billion.

“The most important thing is that we are absolutely thrilled and proud to become the Kenneth C. Griffin Museum of Science and Industry,” said David Mosena, the museum’s president and chief executive officer, although Mosena noted the formal name change will take months to enact.

Mosena “came to me with this as a proposal,” Griffin said, “and having looked at a number of other proposals over the years, I decided that this was something that would be an outstanding way to ensure the long term… (success) of the museum. This is about maintaining the museum at the forefront of being a resource to inspire the next generation of our country in the areas of science and innovation.”

The museum says the gift pushes its current capital campaign past the $300 million mark in funds raised. The money will mostly go into the museum’s endowment, which will more than double as a result, MSI board Chair Chris Crane said.

Chicago, however, did not seem so immediately proud of the name change for the institution at 57th Street and Lake Shore Drive. The MSI, with 14 acres of floor space in a building that is the last holdover from the “White City” site of the 1893 World’s Fair, was Chicago’s second most popular museum in 2018, with 1.56 million visitors. The Art Institute of Chicago had 1.62 million.

Many commenters on Twitter reacted with outrage to the news, drawing comparisons to, for instance, when new owners changed the name of Sears Tower or Comiskey Park. “Nope,” although milder than many, was not an atypical response.

A few, however, noted that most of the other big cultural institutions already have a donor’s name in the title, and we don’t give it a second thought, from the Field Museum of Natural History to the Shedd Aquarium to, more recently, the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum.

“Look, the guy gave $125 million to a cultural institution in the city of Chicago. What’s not to celebrate?” Lariviere said. “I don’t feel any jealousy or resentment or anything. I’m absolutely delighted Ken has done this. It’s a real boost for the city.”

Griffin did not want to engage with social media critics. “Everyone is entitled to an opinion, and I’m not going to wade into that debate,” he said. “What I am going to say is that I’m really excited about the work the MSI does to educate teachers here in Chicago, which they take back into the classroom to educate literally almost every child in public schools.”

Putting a name on a donation helps raise more money, too, he said.

“Being on a number of boards over the course of the last 10 or 15 years, hands down, named gifts are far more impactful in terms of follow-on giving,” said Griffin. “Everybody watches what their fellow peers are doing, and there’s no doubt this gift to the MSI will encourage others to be generous in their giving. Just as Ann Lurie’s gift to Children’s Memorial Hospital has been inspirational to me.”

In the other major Chicago institutional name change in recent memory, philanthropist Ann Lurie gave $100 million — about $121 million in 2018 dollars — to Children’s in 2007, and after a subsequent move from Lincoln Park to a new building in Streeterville, it was renamed the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital. Lurie was a former pediatric nurse at the hospital, while her late husband was a real estate investor.

Griffin also cited as an inspiration the “mind-boggling act of generosity” of Stefan Edlis and Gael Neeson’s 2015 art gift to the Art Institute of Chicago. Their donation of 40-plus contemporary and modern art works, including 10 highly regarded Warhols, was estimated at $400 million in value. But Edlis only gave the gift on the condition that the works be displayed there for the next 50 years. They are currently on view in the museum’s Modern Wing as the Edlis/Neeson Collection.

“It’s clearly an honor. This was not a long conversation,” said Griffin, a multibillionaire commonly cited as Illinois’ richest man. “David (Mosena) and I have talked about a number of ideas for probably a decade. Naming the museum and securing the museum’s financial resources to be involved in our city, our state and our country was a compelling proposition.”

Fortunately for the 2019 MSI, Sears, Roebuck President Julius Rosenwald was the museum’s visionary backer and principal funder before it opened in 1933, and opted not to follow the fashion of the founder class, choosing to keep his name out of the title. Before his death in 1932, Rosenwald gave $7 million toward starting the museum, according to the Encyclopedia of Chicago, the equivalent of about $128 million today.

Rosenwald’s grandson, who lives near the museum in Hyde Park, said he is OK with the name change. Rosenwald “didn’t want his name on it,” said the grandson, 77-year-old Peter Ascoli, who is also Rosenwald’s biographer and clarified that Rosenwald and his heirs had given about $10 million total by the 1940s. “I asked members of my family because I knew this was coming down the pike and they all said, ‘Fine.’ It’s good the museum will have this money to continue strongly into the 21st century.“

From the museum’s perspective, “I don’t think it’s difficult, but I’m a biased party in this because I’ve been offering this for some time,” Mosena said.

“Our name right now is not a branded name,” he added, citing Museums of Science and Industry in Oregon and in Tampa, Florida. “It doesn’t have the personal presence of a major contribution. There are people who may have nostalgic reasons for change not to occur, but I think it’s exciting.”

Crane, the board chair and Exelon Corporation president and CEO, said that the board executive committee working on the deal spent about six months in due diligence with staff and outside counsel “understanding the value of the naming rights of an institution like this. And it’s well in line, if not on the higher side, with what philanthropic institutions have done in the past, or university medical centers, that type of thing.”

Naming an institution for a living person or ongoing entity can become complicated, of course. Remember Houston’s Enron Stadium?

Lariviere, at the Field Museum, said Griffin has earned such an honor and does not seem interested in grandstanding. “Griffin’s an honorable man, and a pillar of the community. I don’t think there’s much risk,” he said. “In our dealings with him he has been really self-effacing and just interested in effective use of his philanthropy.”

The $125 million donation will also put the Griffin name on a new exhibition in the works, “a state-of-the-art digital gallery and performance space that will be the only experience of its kind in North America,” said the institution’s news release.

Mosena described it as a kind of immersive full-room video experience that does not require virtual reality goggles to take part in. It’s being developed, he said, with the Linz, Austria institution Ars Electronica that has a version dubbed “Deep Space 8K.”

Among other Chicago cultural gifts, Griffin has donated substantial amounts to the Field Museum and Art Institute of Chicago, where the central hall of the new Modern Wing was named Kenneth and Anne Griffin Court for him and his now ex-wife.

He has helped major New York museums as well and gave $150 million to his alma mater Harvard University and $125 million to the University of Chicago in the past five years.

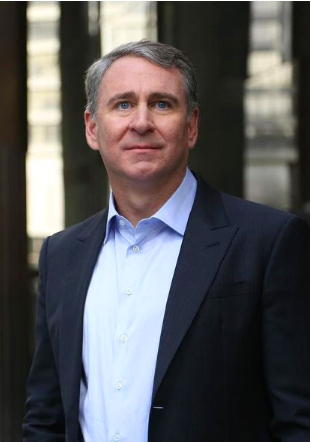

Raised in Florida, Griffin, 50, has long called the Chicago area home and grew up coming here to visit grandparents and going to the MSI, he said. In 1990 he founded the hedge fund Citadel, which said it has $32 billion under management as of Sept. 1. The Citadel website says that Griffin, before the MSI gift, had given more than $900 million to educational and cultural causes.

MSI was founded in 1933 in the building that was the Palace of Fine Arts from the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition and subsequently served as the founding home of the Field Museum.

The natural history museum is named after its principal early benefactor, the founder and namesake of the late, great Chicago department store, Marshall Field’s. After a 2005 acquisition, the flagship Field’s store on State Street had its name changed, of course, to Macy’s.