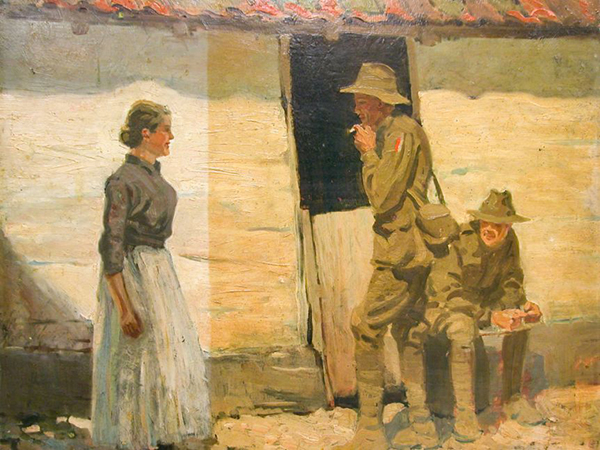

Enzymatic cleaning using saliva is a widely used method in the conservation world.(ABC Central West: Luke Wong).

Luke Wong, Coronavirus puts damper on saliva cleaning method in art galleries and museums, ABC News, 30 June 2020

Like a parent wiping away dirt on a child’s face or a soldier polishing their boots, museum and art gallery conservators often turn to a cleaning solution that’s readily available: human saliva.

When Margot Jolly was handed a historic wood-carved model that required some tender, loving care, the first cleaning solution she considered was her own saliva.

“By using a bit of spit on a cotton bud I could gently clean an area,” Ms Jolly said.

The regional museum consultant said she often favoured the method — also known as enzymatic or natural enzyme cleaning — rather than use a brush or commercial cleaning products.

“It actually gives you a bit more dexterity because you’re paying attention and you’re being careful,” she said.

While cleaning historic objects with a bodily fluid may seem strange to some, Ms Jolly is not alone in its practice.

‘Effective’ conservation tool

Canberra-based conservation business operator Kim Morris said enzymatic cleaning was an age-old, well-documented method he learnt at university many years ago.

“It’s something that has been passed on from mentors to students and cadets and other people who are moving up in the conservation field,” Mr Morris said.

“It’s quite good for cleaning off general grime, smoke, nicotine.”

Sydney-based painting conservator Adam Godijn said “natural enzyme cleaning” was often preferred over other methods because it was non-toxic and readily available with an unlimited supply.

“It’s pretty much second to water in our cleaning choices,” Mr Godijn said.

“The natural enzymes in the spit actually assist in breaking down grease that might be in the surface dirt and actually breaking surface tension.”

However, Mr Godijn said some clients showed surprise when he explained the technique.

“Some people are a little bit shocked and some people are a little bit grossed out,” he said.

“But actually we do clear the surface after cleaning with water and make sure the surface is dry.”

Mr Godijn said, historically, conservators had been known to use bread to clean paintings.

While that method is long gone, he said saliva would endure.

“As such a gentle, cleaning method, I think that it’s going to be hard to beat for a long time,” he said.

Australian War Memorial senior paintings conservator Alana Treasure also stands by the technique.

“Sometimes it’s just the most effective thing and we would always prefer to use the most effective and safe method,” Ms Treasure said.

She said hygiene control methods were in place and items treated with saliva were then thoroughly cleaned and often displayed behind glass.

Caution over cleaning method

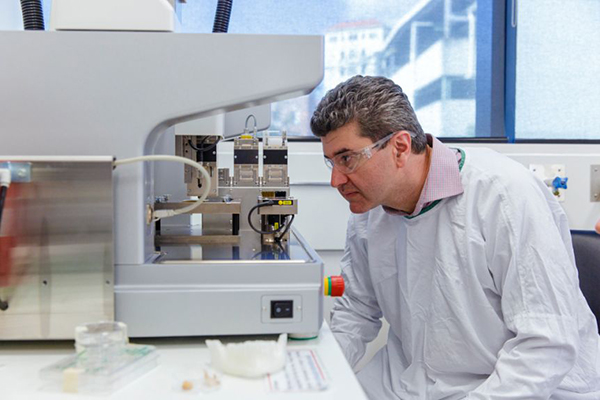

The director of research and professor of periodontology at the University of Queensland School of Dentistry, Saso Ivanovski, has studied how saliva can spread diseases, including COVID-19

“We know bacteria and viruses live within the mouth, they’re very abundant within saliva and hence it’s definitely a potential way for a disease to spread,” Mr Ivanovski said.

While Mr Ivanovski said he was unacquainted with natural enzyme cleaning and such practices might need rethinking.

He said, as a substitute, practitioners could explore the use of “artificial saliva” products designed for patients with dry mouths.

“These sorts of products could be used for cleaning to take advantage of the enzymes that would be in saliva without the downside of the bacterial or viral transmission,” he said.

Mr Ivanovski said items cleaned with saliva might have to be “quarantined” for several days to minimise the risk of transmitting diseases.

“Once saliva is taken out of the body, certainly the viruses and bacteria will not be viable and die off,” he said.

“That’s likely to be, at the very least, hours and certainly, potentially, several days.”

Venues halt technique

Several major venues have already taken precautionary measures since the emergence of the coronavirus.

The National Museum of Australia told the ABC it “would not permit the use of saliva during the current COVID conditions”.

Meanwhile, the National Gallery of Australia’s head of conservation, Debbie Ward, said the pandemic prompted a decision to not continue enzymatic cleaning for health safety reasons.

Ms Ward said records showed “well over 100 works from the collection” had been treated with this method.

But visitors should not be concerned because the period between the cleaning, drying and hanging of an artwork was often long, she said.

And besides, viewers shouldn’t be touching the artworks on display.

“To be totally honest, unless somebody was licking the surface of the painting — which would not be recommended — it’s perfectly safe,” Ms Ward said.