Musicians Jack and Rai perform for their fans on Instagram Live, after their regular performances in nightspots were cancelled due to the outbreak in coronavirus (COVID-19), at their guitar shop in Singapore on 5 April 2020. (Photo: REUTERS/Edgar Su).

Alastair Gornall, COVID-19 has shown Singapore digital arts and humanities are quite the essential service, CNA, 21 June 2020

More thought can be put into digitising archives and collections to make them more accessible and inclusive says SUTD’s Alastair Gornall.

SINGAPORE: I will be taking my students next week on a tour of the Borobudur heritage site in Central Java, Indonesia.

We will climb the vast hilltop monastery and admire the many Buddha statues and bas-reliefs depicting ancient tales of sacred lives.

We won’t wear face masks or worry about social distancing since we will travel together virtually using a combination of Zoom and the recently digitised heritage site on Google Maps.

While COVID-19 represents an unprecedented challenge for the arts, culture and heritage sectors in Singapore, it has been striking that in defiance of the pandemic, we have still found new technological ways to turn to the arts and humanities for inspiration, solace, and fellow feeling.

Cinematic performances, shows and podcasts have filled the spaces of our coronavirus circuit breaker period.

The recent fracas about whether the arts are an essential service only points to the value many see in them.

This is an excellent juncture to think more critically about the nature of the digital arts and humanities, their role in society, and their potential to serve Singapore’s interests on the international stage too.

1. MORE THAN A SUPPLEMENT

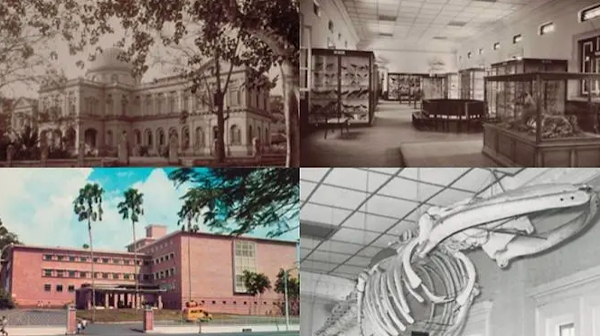

The widespread application of digital tools and technology in the arts and humanities is a fairly recent development. Within the last ten years, Singapore’s cultural institutions have achieved remarkable success in several ambitious digital initiatives.

The National Library has digitised some of its collections and has made them publicly available through BooksSG. The Tamil Digital Heritage Collection, in particular, is a wonderful community-led initiative that digitised Tamil works composed in Singapore between 1965 and 2015.

Galleries and museums too have curated digital exhibitions and have developed a digital archive of their artefacts in roots.sg, the interactive heritage portal launched in 2016.

COVID-19 has brought new attention to these resources and has reinforced the fact that digital projects are more than simply an embellishment. With no way to leave our homes, virtual objects, whether images, films or recordings, have become a replacement for the real thing for many of us.

In our Digital Humanities Minor at SUTD, many students have been working with such digital objects and using their computational skills to draw new insights from them. The absence of many comprehensive digital collections, however, suggests there is still fundamental work to do.

We should also start to think of digitisation not simply as a back-up but as a means of enhancing and improving access to our collective knowledge.

While historical documents in the National Archive are being usefully scanned and uploaded on its website, many of them are not searchable and some have been stamped with digital watermarks.

Without modification, this form undermines the utility of these documents for more advanced forms of computer text analysis. There is scope going forward to think carefully when digitising about how to maximise the analytical potential of archives, especially as new technological tools develop.

2. A LUXURY WE CAN AFFORD

Like the arts, the humanities are sometimes unfairly viewed as a societal luxury and the “non-essential” service of academic disciplines. This is understandable.

When national circumstances are humming along, the cultural and historical aspects of social cohesion can become something we take for granted.

Yet in times of crisis like the outbreak we’re living through, tensions bring to the fore society’s faultlines, which may be primarily economic but are also deeply entangled with culture, religion and history.

The arts and humanities thus play an incredibly important civic role as a public source of authoritative knowledge, in promoting mutual understanding, and in providing a representative platform for social inclusivity.

Digital tools provide an opportunity to expand and enhance this core work. During the COVID-19 crisis, culture has become far more accessible through new digital platforms.

A wonderful example is the National Arts Council’s A List platform that has brought together digital content from Singapore’s arts and culture scene.

Moving ahead, digital platforms have the potential to provide a more inclusive and diverse cultural space than is possible in physical libraries, galleries, and museums.

There are already good examples of how this can be done. Ishvinder Singh’s Sikh Heritage Trail mobile app is an excellent resource for understanding the story of Sikhs in Singapore, a history marginally represented in the National Museum.

And yet, while digitisation may increase accessibility and inclusivity, attention must be paid to the potential risks and problems of digital platforms.

The push to digitise as a means of free distribution risks making the arts and culture sectors less economically viable.

If smaller entities allocate more of limited funds or grant money to digitisation, it could also lead to less support for high-quality content and research.

Digitisation then does have an economic cost. If it cannot be more strongly supported by the government on top of current funding, greater private sector involvement could be encouraged, perhaps by offering tax incentives.

3. REACHING OUT BEYOND THE NATION

One consequence of the perceived civic value in the arts and humanities is that cultural institutions can often be inward-looking places focused only on national stories. Even when collections cut across vast regions and cultures, such as in the British Museum, the nation still plays a symbolic role as civilisation’s custodian.

More recently, however, culture and heritage institutions are reaching out into the international arena, taking collections and exhibits on tour as a means of sharing knowledge, fostering cultural understanding, and strengthening diplomatic ties in ways traditional politics cannot.

As part of this cultural diplomacy, new collaborative digitisation projects between regions and nations have sprouted up, creating virtual platforms that support local heritage while making it universally accessible.

As many retreat into competitive nationalism after COVID-19, Singapore could think more actively about leveraging its digital expertise to lead digital cultural diplomacy in the region.

In 2018, for instance, ASEAN launched its Cultural Heritage Digital Archive (ACHDA), established with the help of the Japanese government and the NTT DATA Corporation.

There is no reason why Singapore cannot be at the forefront within ASEAN in exploring similar projects where digital technologies offer common ground in heritage cooperation.

What is much needed however is for ASEAN’s Committee for Culture and Information to better support regional collaboration between universities and cultural institutions in a similar way to its Committee on Science, Technology and Innovation.

While there are some encouraging digital ventures within ASEAN, regional institutions often look elsewhere for partners. The National Library of Laos recently collaborated with the German government and the Berlin State Library to create the Digital Library of Laos Manuscripts, an online collection of 12,000 historical texts.

The support of global partners is essential for cultural work in the region though the absence of ASEAN in many of these initiatives is perhaps a missed opportunity for greater regional collaboration.

With its expertise in technology, its interdisciplinary world-class universities, and its successful culture and heritage institutions, Singapore could spearhead digital culture in ASEAN as a means of forging regional ties at a time of increasing nationalism.

Download our app or subscribe to our Telegram channel for the latest updates on the coronavirus outbreak: https://cna.asia/telegram

Alastair Gornall is an Assistant Professor in the Humanities at the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) and the lead of its Digital Humanities Minor.His research focuses on premodern South and Southeast Asian intellectual history.

Source: CNA/sl