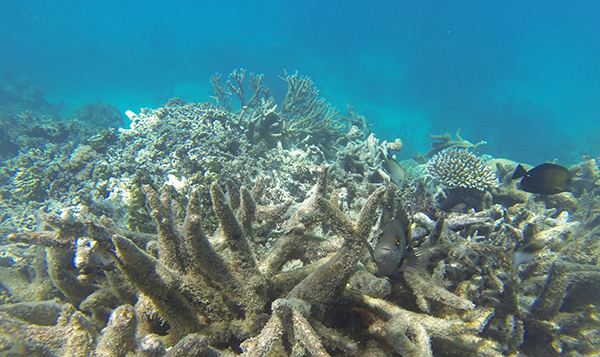

The Great Barrier Reef may be added to Unesco’s List of World Heritage in Danger. Photo: Getty Images.

Carolyn Beasley, The Great Barrier Reef: is Australia doing enough to save marine ecosystem from river run-off and the effects of global warming?, South China Morning Post, 18 July 2021

Unesco will decide this month whether to add the reef system to its World Heritage in Danger list. How much has it deteriorated? We take a dive to have a look. The Australian government has taken offence, but it has failed to meet clean-water and climate-change action targets.

“At the start of every disaster movie, there’s a scientist being ignored,” reads the message pinned to the top of Professor Terry Hughes’ Twitter feed.

The “disaster movie” being referred to is the destruction of the world’s coral reefs.

The Great Barrier Reef is the world’s biggest reef system, comprising some 3,000 individual reefs and stretching 2,300km (1,400 miles) along the coast of the Australian state of Queensland. The country’s pride and joy, especially in tourism terms, was inscribed on the Unesco World Heritage List in 1981.

In June this year, however, Unesco released a draft recommendation to add the reef to its List of World Heritage in Danger. The United Nations’ cultural and scientific agency cited the reef’s deteriorating long-term outlook, which has declined from “poor” to “very poor”, and Australia’s failure to meet its own water-quality targets. Unesco noted the biggest threat to the reef was climate changeand urged Australia to take faster action to meet its commitments under the Paris Agreement.

There are 53 heritage sites on Unesco’s “in danger” list, but, if listed, the Great Barrier Reef would be the first for which the threats are linked to climate breakdown.

Australia’s reliance on the income derived from fossil fuel exports has made it reluctant to embrace climate action. The United Nations-endorsed Sustainable Development Report 2021 recently ranked Australia last out of 193 countries for taking action on climate change. The rating considers emissions from CO2 usage, and imports and exports on a per capita basis. Canberra has resisted carbon pricing and its stance on carbon neutrality is that Australia will “preferably” reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

Nonetheless, Australia’s government has taken umbrage at the UN’s recommendation. Environment minister Sussan Ley said the draft listing had not been discussed with Canberra in advance and that many other World Heritage sites were under threat from climate change. She said the reef should not be made a “poster boy” for global climate issues.

A final decision on whether to add the Great Barrier Reef to the list will be taken by the 21-member world heritage committee, which includes Australia and is chaired by China, during an online meeting that is being hosted by China in Fuzhou.

The attention from Unesco raises the question; is the reef really in mortal danger?

“Yes,” say five high-profile marine scientists who wrote to Unesco to thank them for shining a light on the situation: professors Hughes and Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, of the Australian Research Council’s Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies; Andrea Grottoli, president of the International Coral Reef Society; Johan Rockström, of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Research in Germany; and pioneering American marine biologist Dr Sylvia Earle.

The Great Barrier Reef faces two main threats, explains Hughes; marine heatwaves caused by climate breakdown and declining water quality associated with river run-off.

Five years ago, Australia averted an earlier attempt to have the reef inscribed on the “in danger” list by developing the Reef 2050 Plan, setting water quality targets to minimise the amount of sediment, pesticides and herbicides flowing offshore, towards the reef. However, any progress made has not halted the degradation.

“Australia itself has documented the failure to reach these targets,” Hughes says.

The five scientists believe the Australian government should accept the assistance of Unesco. “The whole point of being listed ‘in danger’ is that it triggers a plan,” Hughes says. “There are many World Heritage properties that have been on, and then off, the World Heritage in Danger list. One example is the Galapagos, another is the Belizean fringing reef. Those countries worked with Unesco to work out the problems.”

One of the main reasons the Australian government is sensitive about the reef is its importance to tourism. In a typical non-Covid-19 year, the reef contributes about A$6.4 billion (US$4.7 billion) to the Australian economy and supports 64,000 jobs. The government worries that if tourists suspect the reef is dying, they will not visit.

Individual tour operators on the reef may not have much of a say in national climate policy, but they do have good intentions, collaborating with the government’s Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and doing what they can to assist on their patch: culling the coral-devouring crown-of-thorns starfish, running coral nurture programmes and replanting pieces of broken coral.

Some support the Master Reef Guide Programme, which ensures high-quality information is disseminated in the hope that it will inspire reef protection and personal action on global warming.

Climate breakdown threatens corals around the world, including the smattering around Hong Kong. Science and innovation are needed now more than ever, but need to target the right areas.

In 2018, the Australian government invested A$440 million in the Great Barrier Reef Foundation, which now spearheads 43 research projects aimed at helping reefs become more resistant to climate change.

These projects include coral seeding of damaged areas by assisted larval transport in a fine net. Another involves “cloud brightening” – the projection of seawater into the air with the intention that tiny salt crystals join clouds, strengthening their ability to deflect sunlight and thus keeping the water below cooler.

“Every summer now, we’re on a knife-edge. The background temperatures of the ocean now mean that every summer there’s danger of a major bleaching event.” Dr Anne Hoggett, director of the Lizard Island Research Station.

However, many scientists believe these approaches are ineffective. “It’s still very much at the Petri dish phase, a lot of this research, and without dealing with the causes of temperature rise, it’s a complete and utter waste of time,” Hughes says.

He says future marine heatwaves are likely to kill off many of the replanted or newly seeded corals, and the sheer scale of the reef makes these projects impractical. “It would take about 250 million adult corals to increase the coral cover on the Great Barrier Reef by one per cent.”

It’s important to note, however, that the reef is not dead. The latest Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report, produced by the marine park authority in 2019, assessed 31 components of ecosystem health, taking into account physical, chemical and ecological processes, coastal ecosystems and disease and pest outbreaks.

The report found that about 60 per cent of ecosystem health components assessed remained in “good” to “very good” condition, while the rest were in “poor” or “very poor” condition.

Designated tourist sites occupy around seven per cent of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, and most remain healthy, offering experiences that are still worthy of international acclaim.

To experience the reef for myself, I head to Lizard Island, north of Cairns. The island is home to the Lizard Island Resort and Lizard Island Research Station, owned by the Australian Museum.

In just a few fin kicks from the beach, I encounter the vitality that a healthy reef supports: a curious juvenile green turtle, a harmless black tip reef shark and a shimmering giant clam in aquamarine.

Since 2014, Lizard Island has suffered two cyclones and four bleaching events, when warming water forces corals to expel the algae living in their tissues, putting them under great stress. Although scientists say the species composition is not the same as it was before 2014, the coral here is doing well, given the circumstances.

“It was annihilation, unbelievably bad,” says Dr Anne Hoggett, director of the Lizard Island Research Station, of the recent bleaching and cyclones. “And [the coral] has come back, not everywhere, but in some places – amazingly.”

However, Hoggett, who has lived on Lizard Island for 30 years, warns that the conditions that caused the bleaching are becoming more frequent. “Every summer now, we’re on a knife-edge. The background temperatures of the ocean now mean that every summer there’s danger of a major bleaching event. It’s down to whether wet season conditions come in at the right time to lower that heat. Hoping for a change in the weather is not a great management strategy.”

Whether the Great Barrier Reef is added to the Unesco in Danger list or not, Australia, and the world, need to pay attention to those figurative cinematic scientists trying to raise the alarm.

“Australia is very much aware of the science,” Hughes says. “But they’re in denial about their responsibility for climate change.”

See also: China denies politics behind Unesco move on Great Barrier Reef