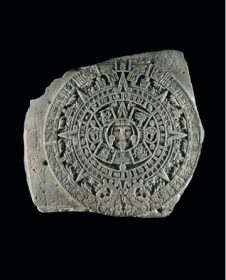

Detail of Aztec statue of Coatlicue, National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City (photo by Estudio Michel Zabé).

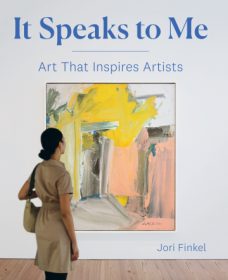

Bridget Quinn, A New Book Culls the Favorite Museum Pieces of World-Famous Artists, 16 August 2019

For It Speaks to Me, Jori Finkel asked 50 artists, from Marina Abramović to David Hockney, “to discuss a museum piece that intrigues or inspires them from their hometown.”

In her recent New York Times review of a show at the Guggenheim Museum curated by artists, Roberta Smith writes about the value of allowing artists free range in museum collections: “They often ferret out neglected or eccentric treasures … and in using the creations of others to make new connections, artists also show new sides of themselves.”

This dual benefit is evident in Jori Finkel’s new book, It Speaks To Me: Art That Inspires Artists, wherein she asks 50 artists worldwide “to discuss a museum piece that intrigues or inspires them from their hometown.” Her specific request is a smart one because it asks artists to highlight work that any of us might experience in person (assuming we can get there). Everything in this lavishly illustrated book (even the “Contributors” section includes a full-color image for each artist) urges readers to make the effort to look. Finkel taps artists not as experts or scholars, but as seers. As people who look for a living.

She opens with a discussion of her “love-hate relationship” with wall labels: “In the field they’re called ‘didactics,’ which may give you a sense of where they can go wrong.” She lists their defects, from boring to overly informative, “Some are loaded with historical detail, conveying information on the obscure duke who commissioned the painting centuries ago.” Full disclosure, there’s no didactic too didactic for my taste, but point taken. This book instead caters to a different kind of nerdiness. That is, a passion for objects, an ardor that reaches across time and space with surprising urgency.

Arranged alphabetically by artist, discussion begins with feminist performance artist Marina Abramović on Boccioni’s Futurist sculpture, “Unique Forms of Continuity in Space,” and ends with James Welling on a staid Wyeth seascape, “Northern Point.” As these two examples amply illustrate, you’d mostly never guess who picks what, which is both charming and enlightening.

There are some exceptions. Mexican artists Pia Camil and Gabriel Orozco each choose Aztec sculptures, for example, which may be unsurprising since it’s shared cultural history, but their reasons are deeply personal. Orozco selects the “Sun Stone,” “probably the most famous sculpture in Mexico,” a work he first saw as a young child while holding his mother’s hand. Earlier in the book, Camil has discussed a statue of Coatlicue, mother of the sun god, “a beautiful image of a woman with two serpents for a head and two serpents as arms” that “combines beauty and darkness, or birth and death.” She describes visiting Coatlicue while pregnant and feeling that “the entire power of femininity, the monstrosity of maternity, was with me.”

This personal connection with art across time is naturally a big theme of the book, as are connections of artistic vision. David Hockney, for example, dissects a surprising Edgar Degas, “Rape of the Sabines (after Nicolas Poussin),” at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena (after reading this book, I made a list of works in California collections so I can see them for myself). Hockney concentrates on the lost pedagogy of copying “masterworks” and, in keeping with his interest in optics, on the technique behind Poussin’s painting, and the Degas copy of it. Hockney mostly ignores what is depicted on canvas (hint: rape) for the professional fascination of how it’s done.