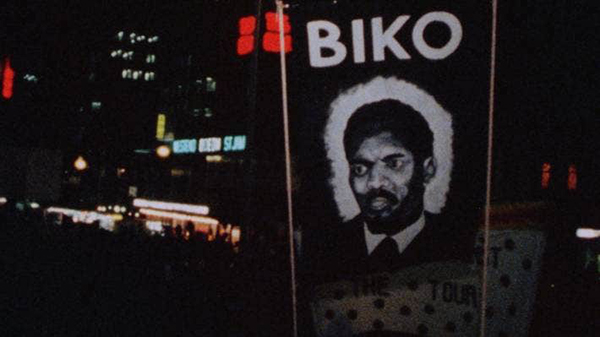

Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision is opening an exhibition, TOHE/PROTEST, about the 1981 Springbok Tour. Nga Taonga Sound & Vision. Courtesy of the Mita Whanau.

Andre Chumko, The 1981 Springbok Tour, as told through objects, Stuff, 7 August 2021

The 1981 Springbok rugby tour was a seminal event in Aotearoa’s social and political history, exposing deep rifts in society. Anti-tour activists argued sport could never be separate from politics, and playing rugby against South Africa condoned apartheid. As Stephanie Gibson, curator of New Zealand histories and cultures at Te Papa puts it: “It’s never just a game.”

While most museums hold items relating to the tour, many have been lost in the ether. This could be because of loss of ownership trail, or physical destruction. Te Papa holds about 40 such items and keeps almost everything it’s presented with, because of their rarity. “It’s like gold,” Gibson says.

As the tour’s 40th anniversary is marked around the country, archivists and preservationists are urging families to consider the history of objects they might carelessly throw out. As well as being material, historical evidence of the tour, they speak to progress made since 1981, and progress still to come. “The clock might stop on this particular protest, but it hasn’t stopped on the issues,” Gibson says.

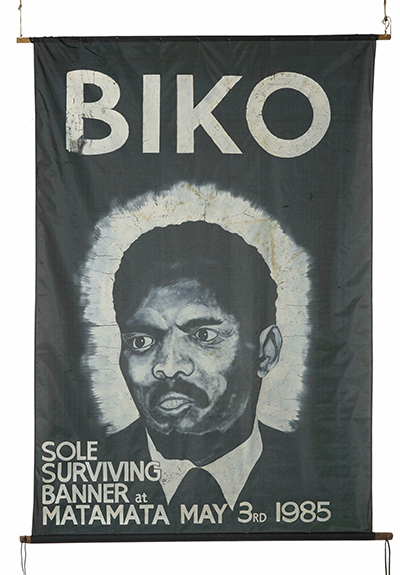

This painted nylon banner, depicting South African anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko, who was murdered in Pretoria in 1977 by state security officers, was made by Graeme Easte, and later gifted to Te Papa. In 1981, the banner was paraded down Queen St in Auckland in response to the worst and most violent test, at Eden Park. The game was being held on September 12, the anniversary of Biko’s murder. The banner was displayed outside the grounds alongside a cardboard replica of a coffin.

In 1985, when the All Blacks tried to tour South Africa, the banner was taken to protests in Matamata. There, it was almost destroyed by pro-tour demonstrators, who tore it and threw eggs at it. Easte noted it was the only banner to survive the day. “Nobody ever cleaned it. It’s a badge of honour,” Gibson says.

The banner is an example of how large objects had presence. It also signifies the number of artists who protested against apartheid. They created posters, placards, and captured many photographs. As a result, there is an amazing artistic record of the tour. While Biko’s face represented the deep-rooted racism and discrimination that existed in South Africa, it was also a way to address Aotearoa’s own issues. “We weren’t talking about our own problems. He’s that bridge to the New Zealand story,” Gibson says.

This Stop The Tour badge, given to Te Papa by Anne Else, was made by anti-apartheid group Hart (Halt All Racist Tours) for protesters to wear. The split black-and-white heart motif was the best-known symbol of the movement, and was designed in the early 1970s as something that was easy for anyone to draw, paint or print.

For those not on the front line, wearing an anti-tour badge was a simple way to declare their allegiance. Tens of thousands of badges would have been made and distributed at protest meetings. Hart met twice a week in different centres around the time of the tour. Hundreds would attend, and they spanned a range of people, including professionals from the larger urban centres – civil servants, church leaders, teachers, university lecturers, artists, researchers, scientists, librarians, public administrators, social workers, office workers and nurses.

Hart, formed in 1969, was just one of many anti-apartheid groups, some of which amalgamated. People also painted their faces black and white, while red – the colour of a stop sign – was also used on the badge. Protesters were adamant in being peaceful, and campaigning by obstruction rather than causing any hurt.

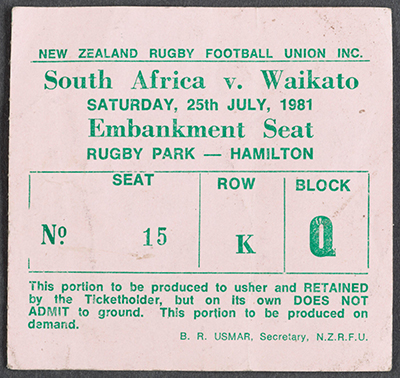

This was a ticket to the South Africa v Waikato game on July 25, 1981. It was issued by the NZ Rugby Football Union, and given to Te Papa by Hart national organiser John Minto in 2009. It was bought by one of about 200 protesters as part of a plan codenamed Operation Wooden Horse. The ticket-holders stood on the embankment of Rugby Park in Hamilton to help create a path through the crowd for a much larger group of protesters approaching by road.

Within moments, the bigger group pulled down the perimeter fence and stormed through. About 350 anti-tour protesters invaded the field, contributing to the game’s abandonment. The cancellation was – in part – due to the perceived security risk from an incoming protester plane. There were violent scenes as rugby supporters scuffled with protesters and pelted them with bottles.

Carefully planned strategies of disruption were a feature of the tour. Protesters also flour-bombed the test at Eden Park, and attempted subverting other events with flares. At Eden Park, because of the Waikato events, the armed forces were in attendance, and barricades with barbed wire had been erected to stop any invasion. Police, in this way, would try to stay one step ahead of protesters.

When Nelson Mandela heard what happened in Hamilton, he said it was like the sun had come out, according to Minto. “There was this little country on the other side of the world sticking up for them,” Gibson says.

This scooter helmet held by Te Papa was worn by John Minto during the tour. Minto was one of the most recognisable faces of the anti-tour movement, and was often seen in front of the protesters wearing overalls and his blue helmet. His girlfriend at the time gave him the helmet after violent clashes with police in Molesworth St, Wellington.

Minto was attacked after the cancellation of Waikato game, being hit on the head with a bottle, then pursued into a nearby house and beaten again by pro-tour supporters. Many front-line protesters wore tougher helmets to protect themselves from police batons and objects thrown by rugby supporters.

Te Papa also holds Rona Bailey’s plastic protective helmet. Bailey, who died in 2005, was left bloodied by a police baton in the fighting in Molesworth St. She was one of 15 communists and radicals listed in a Security Intelligence Service report used by prime minister Robert Muldoon to smear the anti-apartheid movement. Rugby supporters were “baying for protesters’ blood”, Gibson says. “They armed themselves with what they had … repurposed things. We have to protect those stories, so they don’t get lost from the object.”

Tour protesters also used items such as knee pads, shin pads, chest protectors and shields – which they also daubed with images and messages. Much of the protective equipment was made at a large working bee in Trades Hall in the capital.

This moulded resin, metal and plastic police baton, which originated from the United States, was donated to Te Papa by an anonymous source in 1989. The Monadnock PR 24 baton was introduced by police in the early 1980s for riot control, replacing the previous shorter baton. It was used by two specialist police squads formed as security escorts for the South African rugby team, which became commonly known as the Red Squad and Blue Squad. This baton was used by a member of the Red Squad and was abandoned, possibly picked up later by a protester.

Confrontations between rugby supporters and anti-tour protesters grew increasingly violent as the tour progressed. To manage the conflict, police were equipped with helmets, riot shields, and PR 24 batons. The PR 24 baton became a much-feared object, and was nicknamed the Minto Bar. Because of its size, it had to be carried openly, which made its users appear more threatening.

Gibson says police were reluctant and nervous to bring in riot gear, and thought it was a bad look. They weren’t supposed to hit above the chest with batons, but were clearly seen beating people on the head in Molesworth St. Protesters’ injuries made police look unnecessarily violent, and they no longer were able to get away with the line of impartiality. “They looked like they had taken a side,” Gibson says. “It’s a miracle nobody died.”

Merata Mita’s definitive protest documentary PATU!, released in 1983, has recently been preserved and digitised by Ngā Taonga Sound + Vision, the country’s archive for film, television and sound. The original 16mm theatrical release version, which premiered to a standing ovation at the 1983 Wellington Film Festival, runs for 112 minutes, as does the newly preserved film. The shorter 83-minute version was shown at international film festivals, and was not shown on New Zealand television until the 10th anniversary of the tour in 1991. It documents the protests of the winter of 1981 in raw and confronting street-level footage.

Ngā Taonga has recently opened a free exhibition, TOHE | PROTEST, which runs at the National Library to December, exploring how the escalating tensions between activists, the police, rugby fans and politicians were presented by both government broadcasters and activist filmmakers. Mita – who died in 2010 – and other contributing filmmakers risked their lives to contribute footage to the film, says Kate Button, Ngā Taonga public programmes manager. Mita’s son, Hepi Mita, later made a film about how making PATU! affected his mother and their family. It was called Merata: How Mum Decolonised the Screen.