A scientist works in a field of genetically engineered crops in India, a country which has entered the Nature Index top ten for natural sciences. Credit: Pallava Bagla/Corbis via Getty.

Chris Woolston, Nature Index Annual Tables 2023: China tops natural-science table, 15 June 2023

India is another notable riser whereas Russia is among those losing ground.

The latest Nature Index Annual Tables underscore an unmistakable trend in the natural sciences: Western nations are losing ground while China continues to make gains. But underlying this well-established pattern is evidence for the rise of emerging nations and the possible effect of the war in Ukraine on Russian research performance.

Countries, territories and institutions are ordered by their Share, in 2022, of publications in 82 natural-science journals selected by Nature Index. Share, Nature Index’s key metric, measures each nation or institution’s contribution to the Index through the proportion of affiliated researchers they have as authors on each article. Adjusted Share accounts for the small variation in the total number of articles in the Nature Index each year to allow annual comparisons.

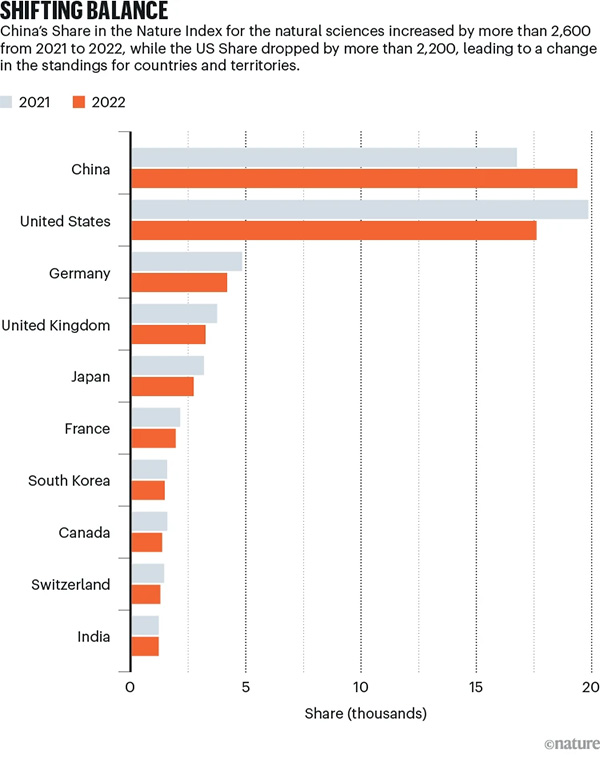

China’s adjusted Share in the natural sciences — which includes the physical sciences, chemistry, Earth and environmental sciences and biological sciences — soared by more than 21% from 2021 to 2022, enough to comfortably surpass the United States for the first time (see ‘Shifting balance’).

“China has been trying to increase its international publications, and has particularly targeted the top-ranked journals,” says Xin Xu, a higher-education researcher at the University of Oxford, UK. She notes that China’s adjusted Share in the multidisciplinary journals Nature and Science rose by 26% from 2021 to 2022, a clear sign that their strategy has succeeded.

In the same period, the adjusted Share for the United States across all of the 82 natural-science journals in the Nature Index dropped by 7%. Both the United Kingdom and Germany lost about 9%, another indication of a shift in the source of high-quality publications. “These results definitely show the changing dynamics” of global science, says Xu.

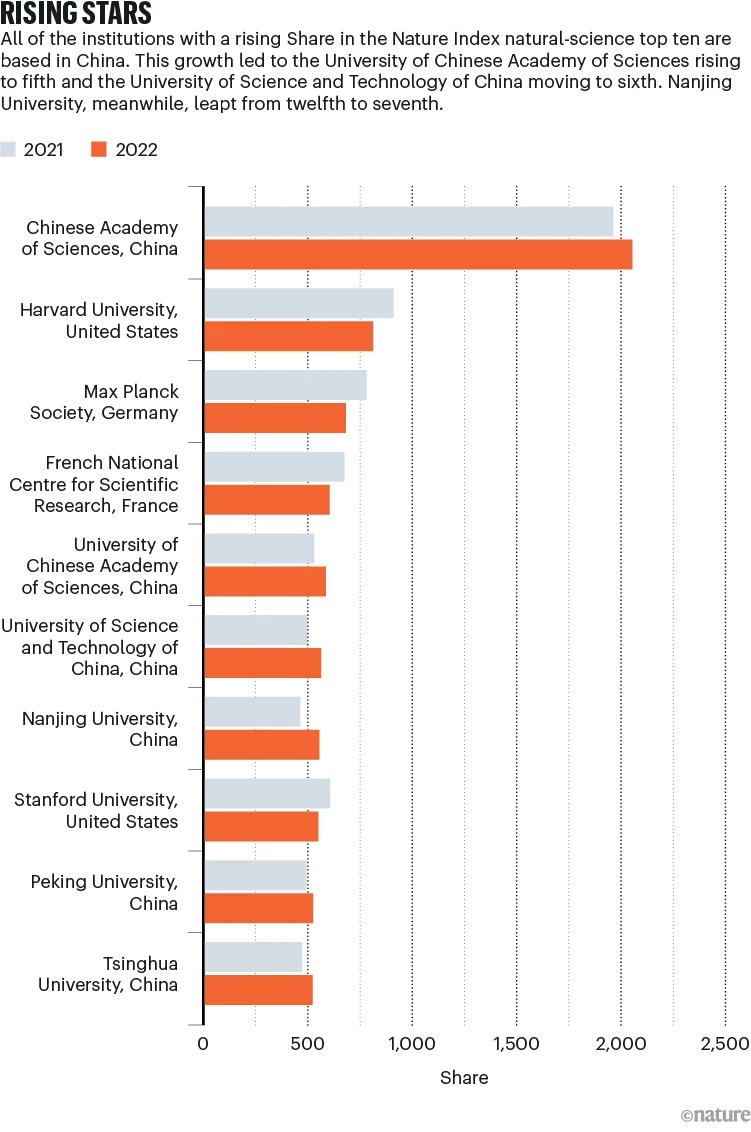

China also dominated at an institutional level. Half of the 20 institutions with the highest Share scores for natural-science articles in 2022 were based in China. Each of those Chinese institutions saw improvements in their adjusted Share between 2021 and 2022, while every non-Chinese institution saw a decline (see ‘Rising stars’). The only institution to come close to bucking this trend was the University of Cambridge, UK, which lost just 0.1% of its adjusted Share.

One subject area in which China is still behind the United States on Share is the biological sciences, a category formerly referred to as the life sciences in the Nature Index. China is catching up fast, however, with a 26% rise in its adjusted Share since last year’s Annual Tables. One institution, Fudan University, in Shanghai, increased its biological-science adjusted Share by 65% during this period.

India on the move

China isn’t the only country making gains. India’s adjusted Share rose by 5%, placing the country among the leading ten nations for the first time. This is a clear sign of progress, but India hasn’t come close to reaching its potential, says Eldho Mathews, a science-policy researcher at the National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration in New Delhi. He notes that the country continues to invest less than 1% of its gross domestic product (GDP) in research and development (R&D), much less than China (2.4%) or the United States (3.4%).

In 2019, India passed Germany to become the fourth-most productive country in the world by the total number of research publications per year, according to Elsevier’s Scopus database. But that productivity hasn’t quashed concerns about quality. Mathews explains that university policies that tied promotions and hiring to the total number of publications helped fuel a surge of papers and created a breeding ground for predatory pay-to-publish journals with low standards. Reforms in 2019 by the University Grants Commission, the major funding regulatory body for Indian universities, have encouraged researchers to seek publications in higher-quality journals, a move that might have helped India improve its standing in the Nature Index and close the quality gap.

Even with incentives, universities in India — there are more than 1,100 of them — still struggle to make significant scientific impacts, Mathews says. “Most of the excellent outputs are from government research institutes, not from universities,” he says. Mathews notes, for instance, that agricultural research institutes in India are highly regarded, while other institutes are making major contributions in the fields of biotechnology and climate-change mitigation. There is also steady progress in artificial-intelligence (AI) fields such as machine learning, he says.

Trouble down under

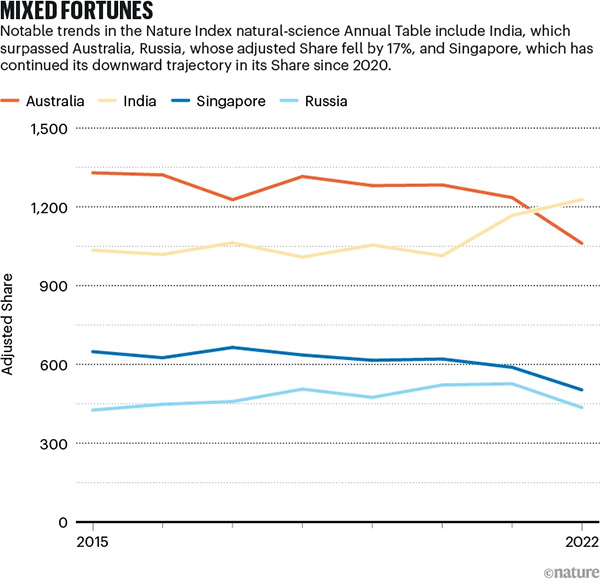

India entered the top-ten countries by Share by surpassing Australia, a country whose score dropped by 14% from 2021 to 2022 (see ‘Mixed fortunes’). That’s just one more sign of a scientific slowdown in a country facing many challenges, says Kylie Walker, chief executive of the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering, a scientific society based in Canberra. Walker notes that federal-government funding of R&D as a proportion of the GDP has been in overall decline for more than a decade. She says that the pandemic also greatly affected the productivity of Australian universities, which strongly rely on the intellectual and financial contributions of foreign students. “Suddenly, things got very tricky, and we were not in a position of strength to start with,” says Walker.

She says that one of the underlying problems is that Australia’s scientific system lacks efficiency and cohesion. “We have more than 200 different federal funding instruments, and they all have slightly different requirements and slightly different time frames,” she says. Walker hopes that the administration that took office in 2022, led by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, will be able to revitalize the system, because the country has “such potential” to tackle some major research challenges, “not just for Australia, but globally”. Ultimately, it needs to reclaim its reputation, she adds, to make Australia an attractive partner for international projects. “It’s impossible for us to get really high-quality science done if we don’t collaborate internationally.”

Shuffling the deck

The latest Nature Index tables might also reflect other notable trends in global science and politics. Russia’s adjusted Share declined by 17%, the biggest drop of any country in the top 20. “The data undoubtedly point to a decoupling of Russian science and intellectualism from the global knowledge networks,” says Simon Marginson, a higher-education researcher and director of the Centre for Global Higher Education at the University of Oxford. He says the invasion of Ukraine and the ongoing war has forced many Russian scientists to abandon international projects. “Collaboration with Euro-American colleagues, previously welcomed by the state, now brings the risk of being named as a foreign agent,” says Marginson.

Ukraine’s adjusted Share rose by 47% while Russia’s dropped, but this was based on a very small Share value compared with Russia.

Some trends lack any clear explanations. Japan — a country with a long history of innovation — saw its adjusted Share drop by nearly 10%. Xu says that researchers in Japanese universities have been relatively slow to embrace international collaboration, especially compared with researchers in China. Also, researchers in Japan continue to publish much of their work in Japanese journals that aren’t included in the Nature Index.

Xu also noted a sharp 15% drop for Singapore, a relatively small, geographically isolated country that faced serious challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. “International mobility is so important for countries like Singapore,” she says. By contrast, Chinese research was able to thrive thanks to a robust domestic system that relied less on outside expertise, says Xu.

Some countries with comparatively modest scientific outputs managed to stay relatively steady in 2022. South Africa and Poland, for example, each rose by 3%, whereas Finland made slightly higher gains (4%). South Korea essentially held firm from 2021 to 2022, losing only 2% of its adjusted Share.

China’s rise in the Nature Index might slow in the coming years, Xu predicts. She points to a shift in national policy, starting in 2020, that encourages publication in domestic journals. Including 2022 Share data from the new Nature Index health-sciences category — which does not allow comparisons with previous years — also pushes China back into second place overall, behind the United States.

Going forward, Xu anticipates a scientific landscape in which no single country dominates publications or sets the research agenda. “We’re seeing a multi-polar world where new powerhouses are coming to the picture,” she says. “It’s a more diversified picture of global science.”

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-01868-3