Geoffrey Munn, How flower arranging became an art form thanks to Constance Spry’s unique view of the natural world, The Art Newspaper, 11 May 2021

An exhibition at London’s Garden Museum pays a floral tribute to one of the 20th century’s most colourful and influential florists.

It is not exactly a story of rags to riches, but Constance Spry, the daughter of a railway clerk, reached the pinnacle of society through trade and art. An exhibition at London’s Garden Museum of around 100 photographs, personal items and artefacts—never before exhibited—will tell the story of one of the 20th century’s most colourful and influential florists.

Spry was trained in bacteriology and sanitary inspection but in 1921 she became principal of a day school in London’s Hackney where poverty and deprivation were rife. Consequently, her true metier came late. It was not until she reached her early 40s that Spry gave up teaching and opened a shop, called Flower Decoration, in 1929. Her first formal patron was Granada Cinemas but it was her daring arrangements of hedgerow flowers in the window of the royal perfumer Atkinsons of New Bond Street that caught the eye of passers-by.

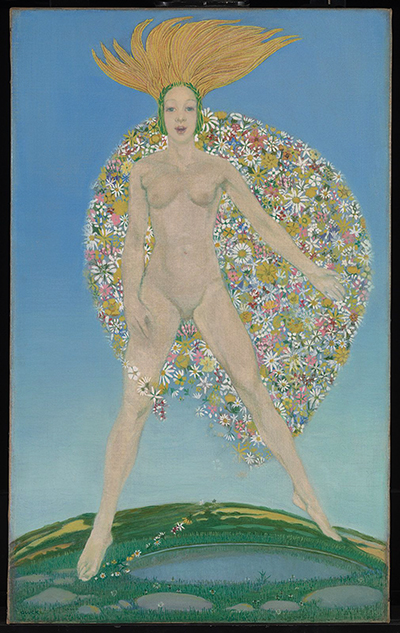

Spry’s business soon took off and after seven years she employed 70 assistants and was obliged to move to new premises in South Audley Street. Clients demanded flair and originality and so Spry turned to Dutch 17th-century artists, learning from them to include fruit and even vegetables in her arrangements.

With the aim of integrating her work into fashionable interior design, Spry used unusual props including wire containers and Neo-Classical columns. Antique vessels were always difficult to find so she designed her own vases in opaque black or white. These were made by the Fulham Pottery in archaic Greek taste but were, by default, a late expression of the Art Deco style.

Eleven years after establishing her business, Spry made a very public demonstration of her sources at a “novel and successful” exhibition at the Cooling Gallery in Bond Street in 1939. To mark the date, it included 39 floral studies, t

wo by the French painter Henri Fantin-Latour, and Spry mirrored them with her own work. According to the Times newspaper, her arrangements blurred the boundaries between reality and illusion.

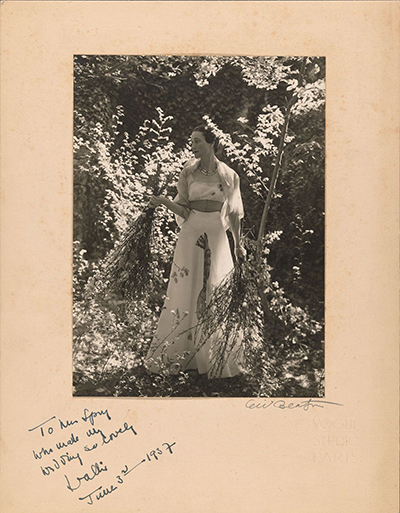

On the strength of a vigorous advertising campaign and numerous books on flower arranging, Spry’s business was on a roll. In 1935 she was asked to arrange the flowers for the marriage of the Duke of Gloucester to Lady Alice Montagu-Douglas-Scott. Only two years later she was working on the wedding flowers for the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. However, her highest honour came in 1953 when she was asked to decorate the annexe of Westminster Abbey for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. It won her an OBE.

Only seven years after that, Spry’s business, perhaps too successful for its own good, was unable to maintain her exacting standards and, like its founder, was in decline. In 1960 Spry fell down the stairs and died shortly afterward. She was 74. Her last words were said to be “somebody else can arrange this”.

• Constance Spry and the Fashion for Flowers, Garden Museum, London, 17 May-26 September