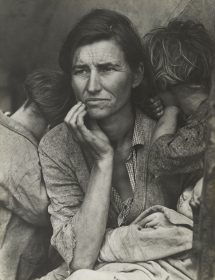

Dorothea Lange, “Migratory Cotton Picker, Eloy, Arizona” (November 1940), gelatin silver print, 19 15/16 × 23 13/16 in. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase.

Ela Bittencourt, Dorothea Lange’s Humanist Vision, Hyperallergic, 30 April 2020

In Lange’s photography, human ingenuity and grace triumph over the unspeakable blows of the Great Depression and other social oppression, even when hope is in short supply.

In the midst of the Great Depression, the American photographer Dorothea Lange crossed the street from her San Francisco studio to photograph unemployed men in a breadline. Lange’s instinct not to shrink from misery but to embrace it evidenced her profound sense of empathy. If we’ve grown a bit immune to it these days, the havoc wreaked on American life — on global life — by the COVID-19 crisis lends Lange’s humanist vision renewed relevance. This spirit is behind the Museum of Modern Art’s current exhibition, Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures. The show, which spans Lange’s entire career and is her first major museum survey of her work in 50 years, stresses the social context in which she produced her images.

The most famous of these date from the New Deal period (1933-36), when the government hired artists to document poverty and unemployment affecting millions of Americans. Lange started at home: In “White Angel Breadline, San Francisco” (1933), a cluster of men huddle with their backs to us, while a lone man in the foreground faces us, his hat pulled over his eyes, his shoulders slouched and arms resting on a wood beam. Lange focuses on his empty cup and ravaged hands, clutched in front of him.

Text is central to the exhibition’s emphasis on narratives. MoMA’s photography curator, Sarah Meister, accompanies the photographs with pages from publications in which Lange’s work appeared, including An American Exodus and Survey Graphic. In the latter, agricultural economist — and Lange’s husband — Paul Taylor (who also co-authored An American Exodus) explains why San Francisco workers are on strike.

Lange’s “Street Demonstration” (1934) accompanies the text. While it’s an essential coupling, the photograph also reminds us that art can arrive at messages sideways. Although we may note first the towering figure of a policeman, hunkering down in front of the crowd, on the left a small child daringly looks straight at Lange. On the right, a short elderly demonstrator opens his feet wide, as if mimicking the policeman’s stance. This multivalent composition — at once committed, serious, defiant, and yet playful— is the true mark of Lange’s craft. In her photography, human ingenuity and grace triumph over the unspeakable blows of the Great Depression, even when hope is in short supply.

Many evocative portraits are of women and girls. In “Woman of the High Plains, Texas Panhandle” (June 1938), a woman clasps her forehead, staring out over empty horizon. Her left hand rests on the back of her neck; her sinewy torso fills the frame. Gentle yet steely, scrappy yet sublime, the image projects resilience. Lange’s notes, which she made often, recap the woman’s words: “This county’s a hard country. They won’t help bury you here. If you die, you’re dead, that’s all.”

In the Farm Administration photographs, there’s the staggering image of a diminutive Black woman, identified only as “Ex-Slave with Long Memory, Alabama” (1937), her right hand clutching a walking stick. A portrait of a young Black girl alone on a ramshackle porch walled off by ivy (“Tennessee,” June 1938) echoes that of a young white girl clutching a barbwire fence (“Child and Her Mother, Wapato Yakima Valley,” August 1939). These are portraits of girlhood forestalled or abandoned.

By contrast, a section devoted to women’s rights and racism (primarily anti-Japanese sentiment and segregation) feels a bit sparse, suggesting that perhaps Lange received fewer commissions in those areas, although there’s at least one striking portrait elsewhere in the show — “Plantation Overseer and His Field Hands” (June 1936). For the most part, however, the exhibition flows well. Audio notes fill in the broader context around the photographs: for example, artist Wendy Red Star, who grew up on a Crow reservation, comments on “Tractored Out, Childress County, Texas” (1938) by drawing a parallel between the Indigenous people pushed out from fertile prairies by white farmers and the same farmers being pushed out by dust bowls. Such contextualization, from multiple perspectives, broadens the social resonance of Lange’s work. It also helps balance the other moments in the show, where the lack of narrative makes it feel like the marginalized groups are being relegated to summary roles or ethnic types (as in “Ex-Slave” or “Filipinos Cutting Lettuce, Salinas Valley, California,” June 1935).

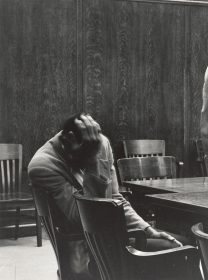

Lange could be ferocious. In her late series, dedicated to the injustices of the legal system, every image is a cry of protest. In “The Defendant, Alameda County Courthouse, California” (1957), a young man sits alone in the courthouse, his broad shoulders slumped, his head in his hand, the latter slightly blurred, spectral, and so massive it shields his face. The immensity of the man’s grief is palpable. In “The Witness” (1955-57), a Black man holds up his right hand in a courtroom; the apathetic faces of white jury members behind him speak powerfully to racism in America.

In Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), Susan Sontag argued that no photograph could tell one story clearly. Lange seems beyond such worry in this exhibition. She had stories she wanted urgently to tell, and moral clarity about her reasons to tell them.

Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures is scheduled to continue at the Museum of Modern Art (11 West 53rd Street, Manhattan) through May 9. The exhibition is organized by Sarah Meister with River Bullock, and assistance from Madeline Weisburg.

Editor’s note: Please note that physical viewing hours for this exhibition have temporarily ended in light of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. The museum has since debuted an online version of the exhibition, and curator Sarah Meister will lead a virtual Q&A with photographer Sally Mann on April 30 at 8pm EST. More details via the link above.