Christine Ro, Is it ever ethical for museums to display human remains?, BBC Future, 20 January 2024

Toward the end of the 1800s, as European settlers continued to encroach on the land of the Bunuba people in what is now Western Australia, Jandamarra became a legendary leader of the resistance. The colonial police searched for him for three years, finally hiring another Aboriginal tracker to find him.

In 1897, the police shot, killed and beheaded Jandamarra. He was around 24 years old. His skull was then sent, as a grisly colonial trophy, to a private museum of a gun factory in Birmingham, UK. The factory was demolished in the 1960s, and Jandamarra’s skull disappeared. Bunuba elders and researchers have been trying for decades to find the skull of this celebrated freedom fighter. The whereabouts remain unknown.

While Jandamarra has become a revered Bunuba figure, museums around the world house the physical remnants of numerous other people – many of whom are anonymous. Increasingly, museums are reckoning with their responsibilities for exhibiting or retaining these, and in some cases considering returns, as descendant communities and others call for more dignity in the treatment of human remains.

What counts as human remains

Defining human remains within museums (or even using the term “human remains”) is not straightforward. The UK’s Human Tissue Act, for example, does not apply to nails and hair, and only requires consent for the use of human remains from people who died within the last 100 years. However, some UK museums take a broader definition.

International standards vary as well. When the Human Remains Working Group of the German Museums Association drew up its first guidelines in 2013, “for our recommendations, it really didn’t matter if a person died 100 years ago or 1,000 years ago”, says ethnologist Wiebke Ahrndt, the chair of the working group. Human remains were defined as all physical remains of Homo sapiens, including hair, teeth or nails that may not have been attached to the person at the time of collection.

Ahrndt explains that certain items were ruled out for practical reasons, such as grave goods and photos of humans, although for certain cultures these also carry special significance. Thus, the National Museum of Scotland has removed all images of (unwrapped) human remains from its online database.

Different cultures also have different beliefs about how human remains should be treated. Ahrndt gives the examples of Tibetan musical instruments made using human bones, and skulls embedded within religious objects in Haitian voodoo traditions. However, in many cultural traditions, to separate or disturb body parts is deeply harmful.

Another area of debate is whether it’s permissible to exhibit human bodies as long as they’re completely enclosed. A good example is Egyptian mummies, which are often “seen more as artefacts than as people”, says Lewis McNaught, whose curatorial work has included a stint in the British Museum’s Department of Egyptian Antiquities. Though these mummies are ancient and often have no body parts exposed, there is an ongoing discussion about whether displaying these humans continues to objectify them, without increasing genuine understanding. (The British Museum was approached for comment, but did not reply before publication.)

Changing attitudes

Edward Halealoha Ayau is a lawyer who has spent 35 years advocating for the repatriation of Native Hawaiian ancestors from cultural institutions. When he and his colleagues started this work, museums displaying human remains were not considering the ethics of doing so.

A sea change has occurred since then, says Ayau. “There’s been a [shift in the] maturity of views with regard to human remains.”

When Ahrndt, the director of the Übersee-Museum in Bremen, Germany, came to the museum over 20 years ago, shrunken heads from South America were on display without explanation or respect for their sensitivity. They were there just for the spectacle, Ahrndt felt, and those were “the first thing I put in storage”. This was followed by mummy bundles with visible skulls from Peru.

The museum explained its reasoning for no longer exhibiting these remains, and there was no backlash. While some museums fear a slippery slope of starting to question and relinquish items, which might end with near-empty collections, that certainly hasn’t been the Übersee-Museum’s experience, says Ahrndt. Its changing policies around human remains have had no effects on visitor numbers or museum funding, she says.

Now, amid conversations around colonial legacies and responsibilities, there’s actually more pressure from the German public and the media to speed up the repatriation of human remains acquired in colonial contexts. “What we realised in the last decade is that the attitudes of visitors in regard to sensitive material have changed,” Ahrndt says.

Today’s museum visitors may not understand why repatriation can take such a long time. While some museums have used legal loopholes to delay the process, in other cases more time is necessary to respect indigenous groups’ decision-making processes. Communities of origin face very complex and emotional decisions on what to do with returned remains, says Ahrndt. For instance, two Toi moko (tattooed Māori heads) that the Übersee-Museum offered in 1999 to the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, in Wellington, were finally handed over in 2006.

One key consideration with human remains in museums is the manner in which they entered the collection. If it’s known that they were acquired illegally or unethically, Ahrndt believes that they shouldn’t be presented to the public in any way. In the Übersee-Museum’s experience, the human remains that have now been repatriated were not initially collected in good faith. “They were against the will of the people,” says Ahrndt. “They were stolen, they were dug out, at nighttime.”

In Ayau’s opinion, since consent cannot be presumed, museums have the responsibility never to display people who are deceased. He points out that when family members pass away and they are buried, for example, it is not with the intent that one day they will be put on display.

Today there’s also more scrutiny of whether there genuinely is any scientific or other academic value to retaining human remains. And where there may be an argument for scientific merit, that is now increasingly weighed against other considerations, including the dignity of the person and the wishes of the community of origin.

Many of the human bodies in Western museums ended up there as justifications for colonialism and scientific racism. The examples are numerous, even just from early-20th-Century incidents.

In Sweden, where Sami women were forcibly sterilised and eugenics research conducted, Sami bones and skulls remain in a number of museums. Human remains were taken from German colonies, then transported to museums, in the false belief that they demonstrated white superiority. In the early 20th Century, an anthropologist at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington (NMNH), DC, collected hundreds of body parts particularly from poor and vulnerable people both within the US and abroad, for what he called the “racial brain collection” and “racial collection of pelvises”.

A representative from the Smithsonian Institution, which administers the NMNH, told the BBC: “The Smithsonian has been returning human remains since 1984. Since then, we’ve focused on returning Native remains, in line with the National Museum of the American Indian Act of 1989. In 2024, we are focusing on non-native remains. In May of last year, the Smithsonian named 13 members for its task force on human remains, which focused on crafting recommendations that address the future of the Institution’s human remains collection. The task force is wrapping up its recommendations to the Secretary, who will issue a revised human remains policy in the next six to 12 months.”

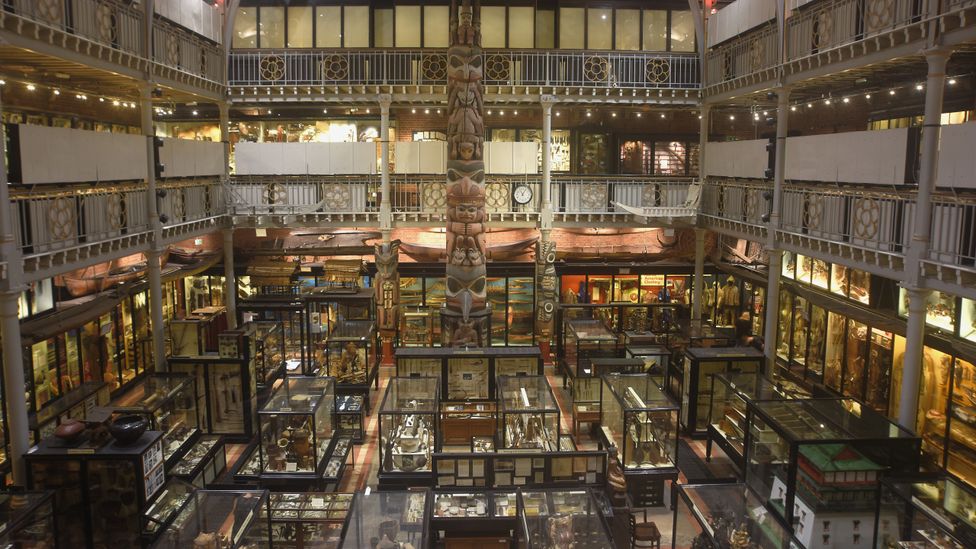

Until 2020, the Pitt Rivers Museum, in Oxfordshire, UK, had South American tsantsa – sometimes referred to as shrunken heads – on display. McNaught, the editor of Returning Heritage, a website about cultural restitution, describes the museum as previously being a “very Victorian museum environment”. However, the museum has now removed 120 human remains from display. This includes the tsantsa, which may have originally come from three Jivaroan peoples, including the Shuar ethnic group. According to the Pitt Rivers Museum website: “The decision was taken to remove the tsantsa from public display because it was felt that the way they were displayed did not sufficiently help visitors understand the cultural practices related to their making and instead led people to think in stereotypical and racist ways about Shuar culture.”

While it’s clear that many museums acquired human parts under pseudoscientific premises, some argue that there are scientifically valid reasons for continuing to display them. For example, in the British Museum, near the delicate bones and skeleton of a young child from ancient Egypt who had the genetic disorder osteogenesis imperfecta, otherwise known as “brittle bone” disease, a sign discusses the role of human remains in studying ancient diseases.

The UK’s Natural History Museum, which is open to continuing to collect human remains, maintains for instance that the chemical signatures of bones and teeth can help to shed light on past population movements. Additionally, skeletal analyses can help to improve the identification techniques used by forensic anthropologists. Some curators believe that technological advancements in the future may allow for more scientific applications for the body parts in museums today.

A representative from the Natural History Museum said “…the Human Tissue Act 2004 requires procedures for consent from the person whose remains were being researched if they died within the last 100 years. And proposals for the public display of remains are subject to approval following consideration of relevant legal, regulatory, ethical and other issues.”

One approach is to remove a controversial human exhibit from public view, but to keep the remains in storage for possible scientific use. McNaught is sceptical of arguments for keeping bodies indefinitely, as DNA samples can be taken now and then the body respectfully returned or buried.

However, not everyone agrees with this approach. London’s Hunterian Museum has the remains of an Irish man with gigantism who died in 1783 within its collection. Before his death, Charles Byrne reportedly went to great lengths to prevent his body from being acquired by anatomists. In the end, the surgeon whom the museum was named after intervened. Byrne’s remains were taken off display before the museum reopened after refurbishment in 2023. According to the museum’s website, the skeleton “will be retained as it is an integral part of the Hunterian Collection and will be available for bona fide research into the conditions of acromegaly and gigantism”.

How to treat human remains with dignity

“It’s really now common practice to review and consider returning human remains,” says McNaught. This has gained the most ground in some Western countries, which in McNaught’s view are far more exposed because of the scale of the looting and removal of human remains that occurred in the past.

However, this is more of a challenge in some former colonial powers in Western Europe. For example, historically French law has made it difficult for public institutions to return portions of their collections. In Ayau’s experience of seeking repatriation of Native Hawaiian ancestors, “the country that is probably most challenging is France”. It is hoped that recent changes to the law may speed up the process.

Additionally, some museums are struggling with their own cataloguing and records, which may be unwieldy. “There are still far too many human remains in in public collections which we can’t even identify where they came from, let alone whether they could be returned to their homeland,” McNaught says. “I think we are still scratching the surface.” Indeed, Ayau says of tracing ancestral remains: “Every time we think we’re finished, we’re finding more.”

Where a return does happen, it can be a form of healing or reconciliation. Ayau has seen it stir up strong emotions from museum representatives, not just communities of origin: “The emotion of repatriation impacts all,” he says.

The Übersee-Museum’s public handover ceremonies have included signing of the official handover documents and the historical “Golden Book” in the Bremen town hall. They have also included apologies from Ahrndt, as the museum director, and the Bremen mayor.

“They took reconciliation very seriously,” Ayau recollects of the ceremony he took part in, which was livestreamed. “It was a great example for others.”

These kinds of apologies aren’t hard for Ahrndt. “The question was more what will actually follow out of that.” Ideally repatriation is not the end of a relationship between museums and descendant communities.

For instance, in 2017, following the Übersee-Museum’s handover of Māori and Moriori remains, partners in New Zealand expressed a desire to work together on cultural projects in the future. Ahrndt agreed but didn’t think it was likely, given limited funding.

However, five years later, the Übersee-Museum sourced funding for a new exhibition in partnership with the Museum of New Zealand, Te Papa Tongarewa. “That was very touching, for both sides,” Ahrndt reflects. “Now I can say, five years later, repatriation is not the end. It is, in fact, the beginning of something new.”

The Übersee-Museum continues to display Egyptian mummy bundles. For now its South American shrunken heads remain in storage, where they are accessible to researchers who have a strong scientific case for accessing them. There needs to be a good rationale for exhibiting people, Ahrndt says. “You always should think: ‘Could I tell my story also without the human remains?'”

And the situation is always changing. Amid continuing controversy, the British Museum and the Smithsonian Institution are both reviewing their human remains policies.

“In a couple of years colleagues will come and say we need new guidelines, and then another generation will rewrite them completely,” Ahrndt says. “I’m absolutely sure about that.” To remain relevant, museums are always changing in line with scientific and societal shifts.

“We’re in a watershed period between the old colonial-type museum, which after all was built to celebrate our colonial history, and brought back trophies from India and Africa and elsewhere, and a future museum environment where there will be no human remains on display,” says McNaught.