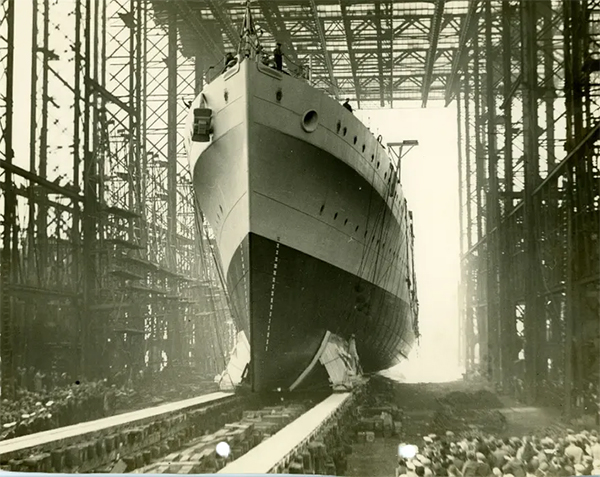

A diver swims near the wreckage site of the Batavia, a flagship of the Dutch East India Company that sank off the coast of Western Australia in 1629, during its maiden voyage from the Netherlands to Java. PHOTOGRAPH BY PATRICK BAKER, THE WESTERN AUSTRALIA MUSEUM.

Ronan O’Connell, Why Western Australia’s coast rivals the Bermuda Triangle, National Geographic, 18 November 2022

At least 1,600 shipwrecks—and countless tales of pirates and plunder—lie offshore, under Indian Ocean waters. Now maritime explorers are diving down to reveal their secrets.

Western Australia’s 8,000-mile-long coastline is littered by at least 1,600 sunken vessels—more than any other Australian state—and these wrecks now lure tourists, thrill divers, and fascinate scientists.

Almost four times the size of Texas—yet with only 2.6 million people— Western Australia (WA) receives few tourists compared to Australia’s more developed eastern seaboard, home to Sydney and Melbourne. The state’s capital, Perth, is 1,300 miles from the nearest city, Adelaide.

But those who journey to WA find that some of its most appealing sites are off its shores, hidden beneath Indian Ocean waves. Here, shipwrecks can be found everywhere from city beaches to far-flung marine parks, and they serve as the focus of a new six-part documentary TV series, Shipwreck Hunters Australia. As well as being superb dive locations, these underwater ruins reveal surprising currents of WA’s maritime history.

Shipwreck coast

From the 1600s, this coast became a burial ground for Dutch, British, and Portuguese vessels, says Ross Anderson, curator of maritime archaeology at Western Australia Museum. Many ships perished on the Roaring Forties sailing route from Europe to Indonesia. They ventured too far east and into the treacherous waters of WA, which are laden with natural booby traps like extreme tides, shallow offshore reefs, towering sea cliffs, and perilous weather.

Human error was the cause of WA’s first recorded shipwreck 400 years ago. Visitors to Perth’s impressive WA Shipwrecks Museum can see a cast-iron cannon retrieved from this vessel, the Trial, which sank about a hundred miles west of Karratha town, in the state’s north, in 1622. They can also learn its scandalous tale.

En route from England to Indonesia, the Trial went off course, hit rocks, and sank. More than a hundred crew members were swallowed by the sea. One of the 36 who survived, ship master John Brookes, lied about its demise to conceal his negligence. This false account hid the Trial’s resting place for three centuries, says Alistair Paterson, archaeology professor at the University of Western Australia.

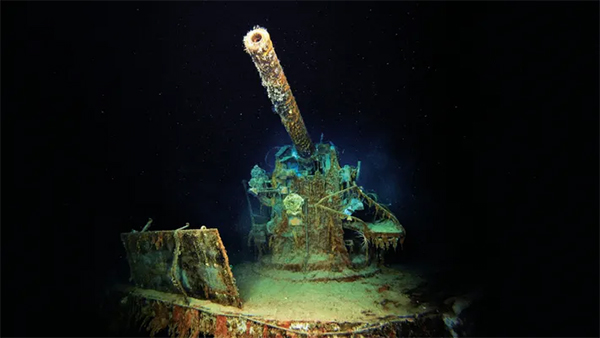

A similarly remote location protected the secret of Australia’s greatest maritime mystery. Perth’s WA Maritime Museum explains to visitors how a thunderous WWII battle between the German HSK Kormoran and Australian HMAS Sydney II sunk both war ships, killing 645 Australian crew and more than 70 Germans in 1941.

Australian media became fixated on the search for these ships, which weren’t found until 2008, about 180 miles west of the WA town of Carnarvon. “The Sydney and Kormoran were difficult to find because of the [wreck] depth of 1.5 miles and difficulties in calculating where the vessels finally went down,” Paterson says.

If that was WA’s worst ocean disaster, the Batavia was its most ghoulish. This Dutch ship headed for Indonesia was carrying more than 300 people, and vast riches, when it struck a reef and sank in WA’s Houtman Abrolhos Islands in 1629.

About 250 Batavia passengers managed to survive, on three small islands. Among them were scheming murderers. The Batavia’s skipper and under merchant weeks earlier had hatched a plan to seize the ship, steal its bounty, and become pirates. More than 120 wreck survivors were butchered by these men and their underlings.

PHOTOGRAPH BY PATRICK BAKER, THE WESTERN AUSTRALIA MUSEUM,

Tourists can dive or snorkel this shipwreck by driving five hours north of Perth, to Geraldton, then taking a boat tour of the Houtman Abrolhos Islands, 55 miles to the west. The remains of Batavia lie just 16 feet beneath the surface. They also can be explored virtually via the WA Museum’s free interactive e-book, Batavia 1629, which uses photos, 3D models, and animations to depict the vessel’s voyage of doom.

Another dive-accessible wreck in the Abrolhos inspired Ash Sutton, one of the Shipwreck Hunters Australia documentary crew, with its story of survival against the odds. The Dutch ship Zeewijk sank in 1726, but 82 of its 208 male passengers miraculously managed to reach Indonesia on a makeshift boat.

“A bunch of [Zeewijk] sailors lived on the shipwreck itself for months while it was perched on a reef,” says Sutton, who now lives on the Houtman Abrolhos Islands. “It’s one of the most remarkable stories I’ve ever heard.”

Sunken mysteries

Tourists need not leave Perth to dive into this state’s maritime history, says marine archaeologist Jeremy Green. The British shipwreck Omeo, which capsized in 1905, rests just 80 feet from the shore in the azure waters of Perth’s Coogee Beach. It is part of the Coogee Maritime Trail, a 750-foot-long snorkelling route embellished by artificial reefs and underwater sculptures.

Further wrecks lie 10 miles northwest of the Omeo, at popular tourist destination Rottnest Island. This car-free haven is ringed by exquisite beaches, surf breaks, and coral reefs, which have sunk a dozen vessels over the past two centuries. These ruins are tailor-made for diving, due to translucent water, shallow depths, and the presence of 25 species of tropical coral.

What tourists can’t explore is the SS Koombana. It has never been found. A Titanic-like, luxury passenger ship, it was ferrying more than 150 people between Port Hedland and Broome, in WA’s far north, when it vanished into the swirling wrath of a cyclone in 1912.

“Several attempts to find Koombana’s final resting place have been made over the decades, and finding the wreck is an outstanding maritime mystery we would love to solve,” says Ross Anderson.

More than 400 years after it became a colossal ocean graveyard, Western Australia still holds seafaring secrets.

Ronan O’Connell is an Australian journalist and photographer who shuttles between Ireland, Thailand, and Western Australia.

Shipwreck Hunters Australia is streaming on Disney+. The Walt Disney Company is the majority owner of National Geographic Partners.

See also: Shipwreck Hunters Australia