Thylacine pouch-young preserved in jars. Courtesy of the University of Melbourne.

Mary Ann Jolley, Back from extinction: Resurrecting the Tasmanian tiger, Al Jazeera, 29 January 2023

Hunted and exterminated, the last thylacine is thought to have died in the 1930s. Meet the scientists who want to bring it back.

Wearing a hooded sweatshirt, jeans and sneakers, with a notebook and pen in his hand, Andrew Pask bounds through the gothic sandstone arches of Melbourne University’s historic quadrangle on a chilly October afternoon.

He could pass for a student, but in fact, the 48-year-old is a professor in the bioscience department who is promising to lead a team of scientists to do what humans have never done – bring an extinct creature back to life.

A collection of Star Wars paraphernalia, and miniature skulls and dinosaur replicas are meticulously arranged on the base of his desktop computer, but front and centre is the subject of his ambitious project – its stripes and wide-yawning jaw, unmistakably a thylacine, or, as it is more commonly known, a Tasmanian tiger.

“I think there is nothing that approaches the incredibleness of the Tasmanian tiger,” he enthuses as he moves his mouse across a pad covered in a 1930s black-and-white image of one of the last living thylacines.

“The fact that it’s an incredibly amazing, beautiful marsupial that was brutally hunted by humans to extinction, we actually owe it to those species to apply the time and the money to return them back to the ecosystem and restore some of these wrongs that we’ve done in the past,” he says.

Native to Australia and Papua New Guinea, the thylacine disappeared from the mainland and its northern neighbour more than 2,000 years ago. Some blame its demise on the arrival of the dingo, another apex predator, but others argue that is debatable.

There is no debate, however, when it comes to what happened to the 5,000 or so thylacines that once inhabited Australia’s southern isle, Tasmania.

Their fate was sealed with the arrival of 19th-century British colonists. Committing what many believe was genocide against the Indigenous population, the colonists also turned their guns on the state’s top predator.

Nick Mooney, a biologist, conservationist and arguably Tasmania’s foremost thylacine expert, shakes his head as he utters solemnly, “It’s a grim tale.”

Perched on a rock under a tree on the edge of an inlet leading to Bass Strait, a treacherous body of water that has separated the island from the mainland for the past 14,000 years, he explains how it was colonists who dubbed the seemingly shy, nocturnal marsupial, the Tasmanian tiger.

“A lot of English people were familiar with tigers from India and so because the thylacine had stripes, or bands, they called it the tiger.”

“As the colony settled in and sheep arrived, a conflict started immediately. At one stage there was a claim that more sheep were killed [by thylacines] every year than were actually sheep in Tasmania. It was just classic tabloid rubbish,” he says, seething with condemnation. “So the bounty was installed and that really was the death knell for the thylacine.”

Private bounties on the Tasmanian tiger were introduced as early as the 1830s, with the government weighing in at the end of the 19th century. And if they escaped being killed for money, many became casualties of traps intended for other animals.

Hunted to extinction

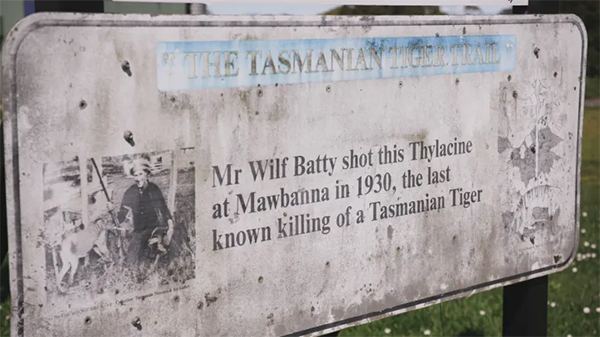

The last wild thylacine is believed to have been shot in 1930 by Wilfred Batty, a farmer who hailed from Yorkshire. He spotted it prowling near a shed housing chickens on his farm at Mawbanna, in the northwest of the state. The fertile farming region was prime thylacine habitat.

Batty’s grandson, Bevan Anderson, still lives in the area. Sitting in a neighbour’s lounge, he rests in his lap a now famous photograph of his grandfather – the smiling farmer holding his gun as he crouches between the fatally injured thylacine and his terrified dog.

“I’m not sure whether that’s something to be proud of or something to be ashamed of,” he says, moving uneasily in his seat. “But in those days, I guess his livelihood was being threatened. I think they were stealing his chooks. So, he had to protect them. If he had known it was the last one, I don’t reckon he probably would have done it.

“I believe that,” he adds as his eyes drift back to the photo.

A victim of cruel neglect

In the basement of Hobart Museum’s storage facility, recently retired senior curator and thylacine specialist, Kathryn Medlock, pushes back the compactus. Fluorescent lights flicker on, revealing shelves packed with labelled boxes. Carefully removing one, she takes out a skull of a thylacine.

“This skull here is interesting because it’s got a bullet hole in it,” she says, pointing to the gaping hole in the forehead.

She explains how the museum paid money for thylacine specimens. According to her catalogue, one mounted thylacine was captured by a trapper in 1928 and sold to the zoo for 25 pounds. When it died, the museum bought it from the zoo for 5 pounds.

“It’s strange because the museum was involved in collecting, but at the same time, three museum directors really pushed for thylacine reserves, legal protection, limits on hunting and trapping to try and prevent them going extinct. So, it’s a bit contrary in some ways,” she shrugs, bewildered.

The only moving footage in existence of the thylacine is of those held in captivity. The penultimate surviving thylacine was filmed soon after he was captured and brought to the Hobart zoo. The grainy black and white video shows the striking male in distress, pacing back and forth along the wire fence of its small, stark, cement cage. The images are haunting but have ensured the species is never forgotten. The animal is now an icon of human-induced extinctions. Australia’s annual national threatened species day is held on the anniversary of the last one’s death.

Sightings abound

Despite the International Union for Conservation of Nature declaring the thylacine extinct in 1982, cohorts of enthusiasts in Tasmania and far beyond its shores share the belief the exotic creature still roams the wilderness.

“There’s been thousands of sighting reports. I’ve met many people who firmly believe that they’ve seen thylacines. They’re absolutely convincing. Whether they did or not is a completely different issue”, the 69-year-old conservationist Mooney says, chatting away as he drives through dense bushland to a site from which he led a 12-month search for the thylacine in the same year it was pronounced extinct.

In 1982, one of his fellow senior government parks and wildlife service officers, Hans Naarding, was observing birds in the area and at the end of the day decided to bunker down in his 4WD for the night. Recalling Naarding’s account, Mooney says, “He woke up, flicked the spotlight around and bingo! There’s this thylacine standing three or four metres away from his vehicle.”

Mooney’s rigorous search found no evidence of a thylacine, but that doesn’t necessarily mean he disbelieves Naarding or that he thinks the thylacine couldn’t have survived for decades beyond 1936.

“I think it’s the most extraordinary bit of human arrogance to think we caught or killed the last one,” he says emphatically.

The spirit lives on

Indelibly etched in the island state’s identity, the Tasmanian tiger, or, Tassie tiger for short, adorns vehicle number plates and is a tourist drawcard, with small towns trading on it.

Not surprisingly, the bar owner Doug Westbrook is a true believer. He says, “I believe I saw one. My wife will say she definitely saw one.”

And some patrons even come along with video evidence from cameras they have attached to trees in the bush. But like the countless number of similar videos posted on social media, the evidence is “inconclusive” as far as experts like Mooney are concerned – the images too blurred, too abstract or simply of other animals.

“There’s been lots of false alarms and lots of want-to-be evidence, lots of wishful thinking. But I’ve seen nothing that I think is evidence of a thylacine,” Mooney says. But the scientist in him won’t let him completely rule out the possibility it’s still lurking around. “Some colleagues of mine get quite cross with me because I won’t say it’s extinct … In fact, science doesn’t ever say that. All it can really say is it’s very unlikely. And I would agree it’s very unlikely there are any thylacines there, but you can’t say they’re not.”

Like Scotland’s Loch Ness Monster, the Tasmanian tiger has not only bewitched ordinary folk, but writers and movie producers, some of whom appear to have literally lost the plot over it. The 2011 film, The Hunter, is a case in point. Starring Willem Dafoe as a mercenary sent to Tasmania to hunt and capture all surviving thylacines, its premise that the animal’s DNA holds the secret code for a dangerous weapon borders on ludicrous.

And then there are the hard-headed media moguls who have also become engrossed with it. In 1983, American Ted Turner offered a reward of $100,000 to anyone who found one and in 2005 Australia’s Kerry Packer upped the ante, his magazine, The Bulletin, offering more than $1m.