Judith Hickson, Collecting the pandemic: Connecting past and present, Queensland Museum Network, 13 April 2023

Since early 2020, Queensland Museum’s social history team has been collecting objects and stories from the SARS-Cov2 pandemic. As we enter the fourth year since the outbreak, it’s timely to look back on some of the items we’ve collected so far as we continue our mission to document this important time in our world’s history.

On 10 January 2020, Australia’s ‘Black Summer’ bushfires occupied most media and public interest. Australians could be forgiven for paying little attention to reports of the first death from a mystery ‘pneumonia-like’ illness in the city of Wuhan, in southern China’s Hubei Province. Though many scientists and health experts expressed their concern, none could have foreseen the far-reaching consequences and what lay ahead for the world in the wake of this report.1

Just two weeks later, on 25 January, Australian health authorities identified the first case of in Melbourne in a traveller returning from Wuhan.

By March 2020, a global pandemic had been declared by the World Health Organization, Australian borders had closed to all non-residents and the Australian government had announced a State of Emergency. A progressive series of lockdown restrictions and physical distancing rules were put in place to limit the movement and gathering of people outside households.

As Covid-19 cases continued to grow and expand exponentially, museums around the world simultaneously recognised this as a crucial time to collect objects and stories to document this watershed moment for future generations.

1Qin, Amy; Hernández, Javier C, ‘China Reports First Death From New Virus’, The New York Times, 10 January 2020.

Learning from the past

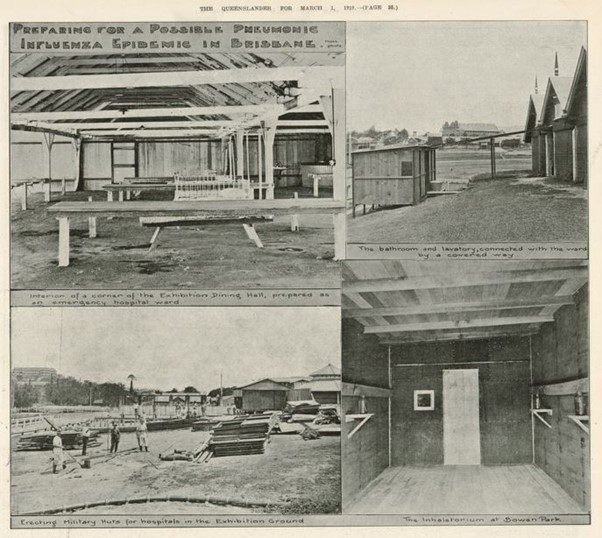

At the outbreak of the pandemic a hundred years ago, Australia was reeling from the devastation of world war. At the same time, humanity was confronting a deadly influenza outbreak with an eventual death toll greater than the total number of military and civilian deaths that had occurred during the conflict. With no antibiotics or vaccines, the 1919 pandemic is thought to have claimed at least fifty million lives worldwide.

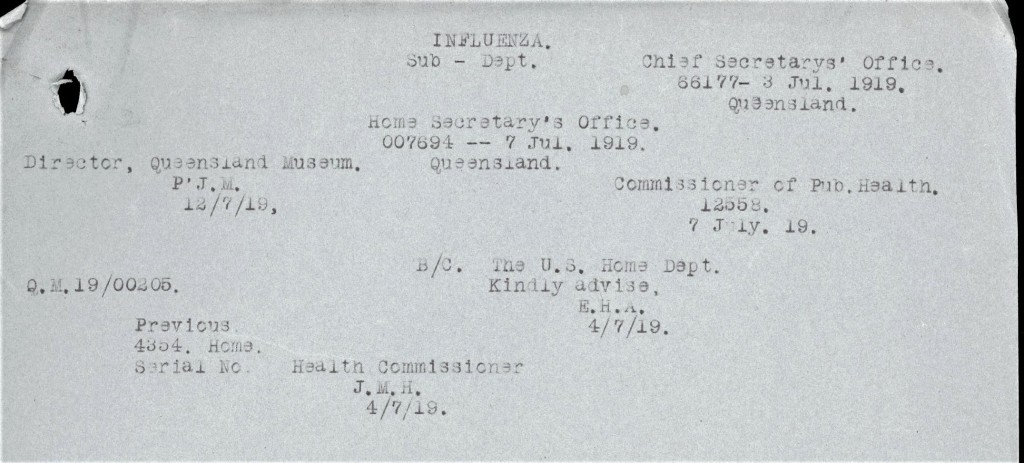

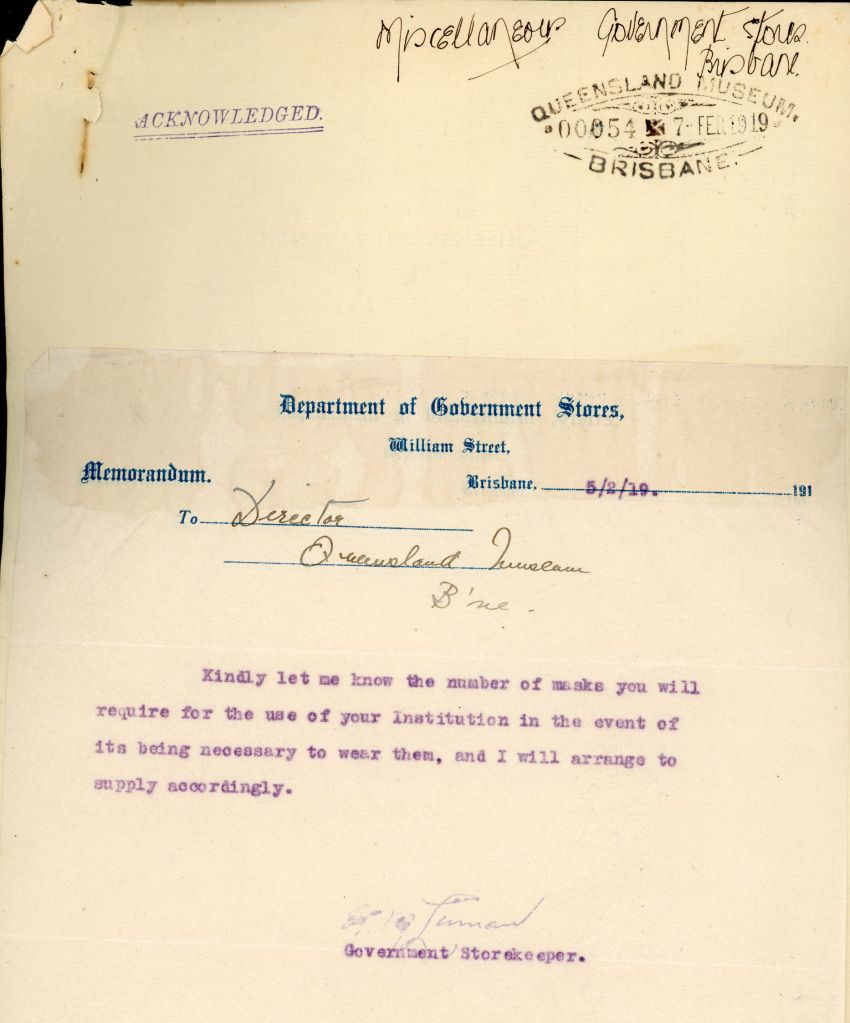

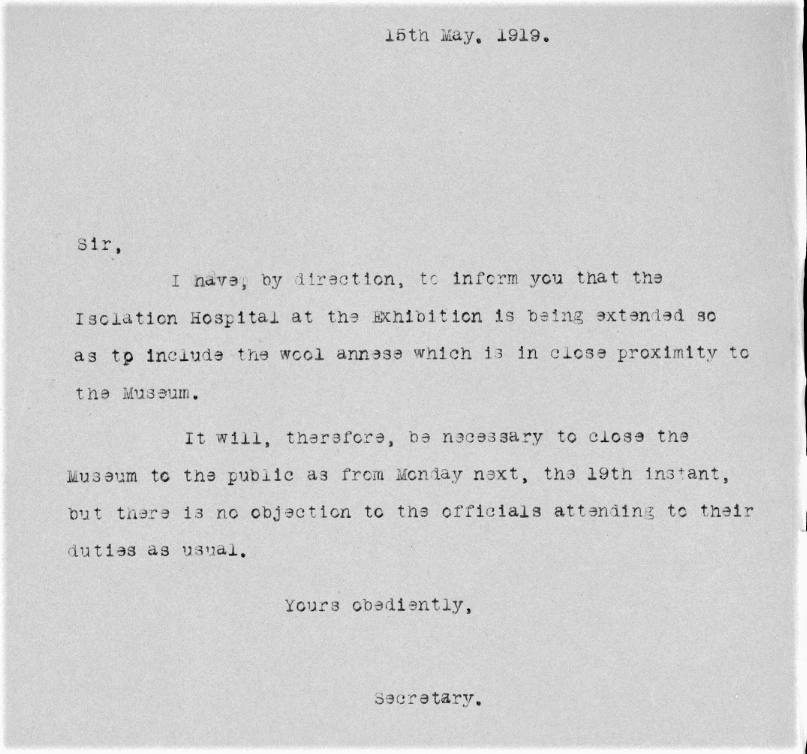

Despite the human toll, no mementoes or artefacts exist in our collection to tell the story of this time. Emerging from the wreckage of war and amid unimaginable loss of life, Queensland Museum’s attention was, like most of the world’s museums, understandably, on recovery and restoration. Only a handful of letters from our correspondence files attest to the Museum’s closure and mask wearing by staff at that time. In the aftermath of the pandemic, the disease which had ravaged the post-war world quickly disappeared from public consciousness.

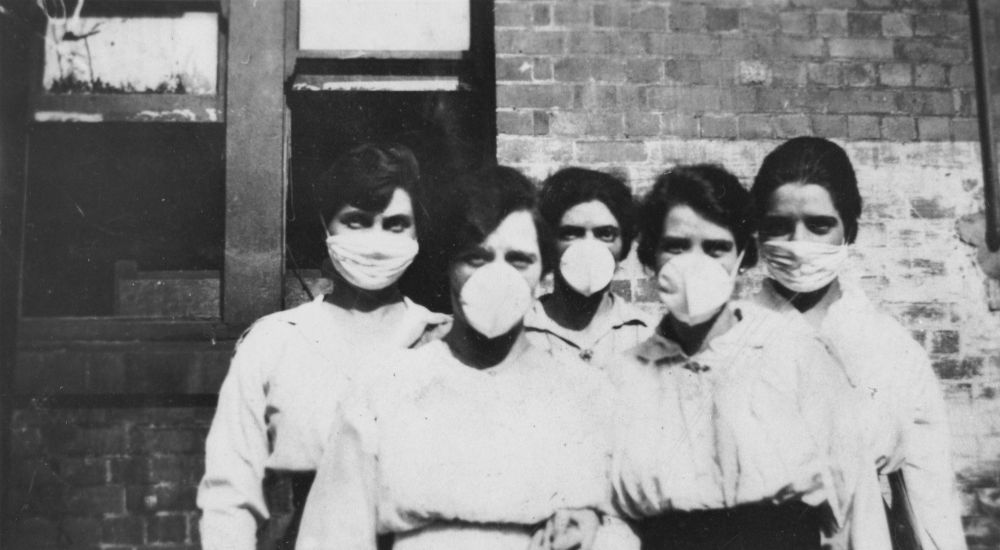

As noted by Queensland historian, Matthew Wengert, the image below has been widely used in both state and national media, books and writing. It is one of the few photographs that exist in public collections today – an iconic symbol of the women who served fearlessly to confront the lethal contagion which swept through families, homes, neighbourhoods, towns and cities, leaving swathes of death and undreamed-of sorrow in its wake.

Positioning for the future

Many people today are asking when this pandemic will end. We don’t know the answer but one thing we can be certain of is that we, as a community, have been irrevocably changed in ways we might not yet understand.

For those of us looking back at that fateful time a hundred years ago, many actions and events – mask-wearing, border closures, vaccination debates, protests – reverberate across the decades.

Hearing and learning about the lived experience of these earlier times touches a chord deep within us because they have now become our shared collective experience.

-

Road closures in Coolangatta/Tweed Heads 2020 -

Road closures in Goondiwindi 1919. -

Road closures in Coolangatta/Tweed Heads 2020 -

Road closures in Goondiwindi 1919.

As a museum, we are a place for storytelling, providing spaces where we come together to share and learn from our experiences through the objects we collect and display. Stories are seen as a powerful medium to convey to others a sense of what we are currently facing as individuals and as a community. Still, above all, museums are primarily places for objects.

So why do objects matter?

Most notable over the past two years has been the explosion of digital technologies allowing instant access to learning and information. We can now travel virtually and attend exhibitions and events at the click of a mouse. Photographic images have proliferated as photographers around the globe have trained their lenses on the pandemic.

Yet, the fundamental ways – physical, psychological and emotional – in which people experience ‘things’, or material culture, and the physicality of objects themselves, give objects a power beyond words, to engage directly, to excite and inspire curiosity, and to transport us to forgotten or remembered places, feelings and experiences deep within hearts and minds.

For instance, how much more could we understand if we learned not just the names of those courageous women in 1919, but if their masks were placed in front of us today?

In practical terms, we might ask ourselves if they were made from cotton or another fabric? Were they stitched by hand or factory-made? Is every mask the same or is each made differently? Which was most effective in protecting its wearer?

From a physical perspective, we might imagine what the masks would feel like and compare that with how we felt when wearing a mask? On a more profound emotional plane, would we feel anger in remembering the restrictions that were placed on us, or a sense of solidarity and empathy for the wearer?

Through our project to collect from this current pandemic, we hope to gather objects that will prompt such experiences and questions, encourage discovery, and record stories that will resonate with us now and for generations to come.

Community

Unlike the previous pandemic, photographic documentation of the past three years has been widespread and prolific. The community has been integral in the documentation of the pandemic, sending in photographic documentation of their lives in lockdown. Chalked and painted signs of support and hope, teddy bears, playgrounds and sports grounds barred for use are some of the things that speak to our experience and that we hope future generations will not have to live through. These objects shed light on some of the emotions that are otherwise hard to grapple with.

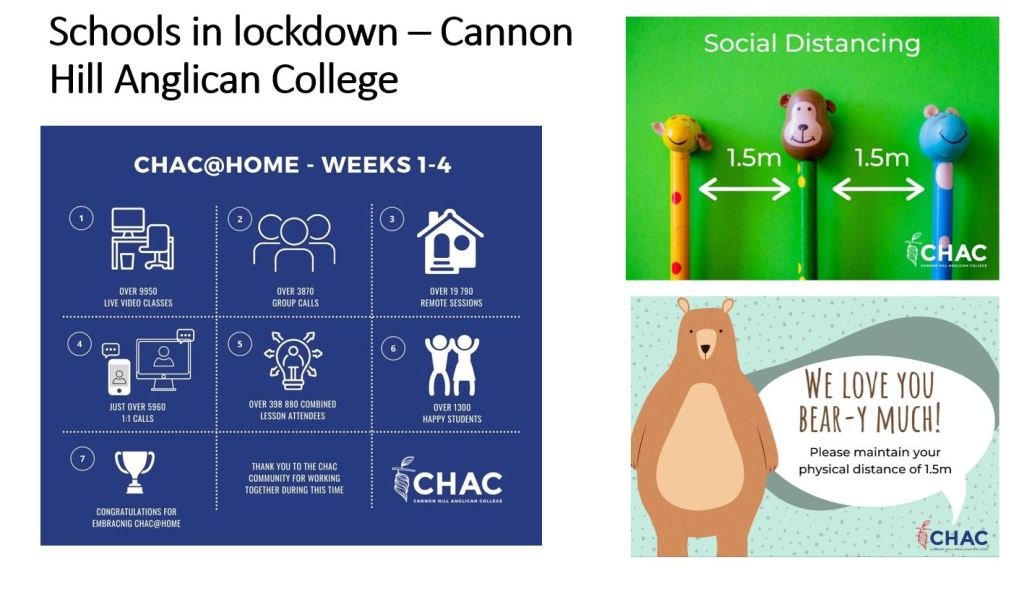

Schools in lockdown

Schooling in lockdown was a major milestone of the COVID-19 pandemic. Schools like Cannon Hill Anglican College contacted Queensland Museum to share their online learning curriculum and digital copies of signage they produced when students returned to their classrooms. So far, three schools have contacted us to offer similar material.

These and many more objects have been acquired in the last two years. Follow our blog over the coming months as we share more stories about what we’ve been collecting.

Donate to the collection

We’ve got a big job to do, and we rely on the generosity of our visitors and supporters to continue our valuable research and share stories that inspire. Object donations are vital and ensure that the collection represents the diversity of stories that make Queensland distinctive. Find out how you can donate to the collection today.

To keep up to date with the latest museum news sign up to your mailing list here or follow us on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.