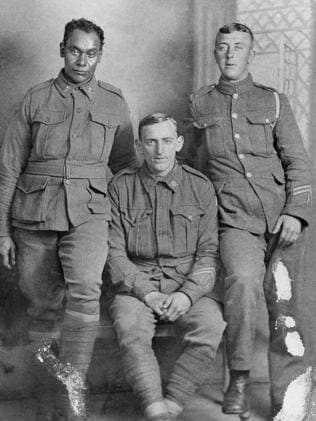

Roland Carter, photographed at Halbmondlager POW camp, Germany. Fotograf: Otto Stiehl Lager Wünsdorf/Zossen.

Tim Lloyd and Peter Monteath, The epic tale of a WWI Indigenous Anzac and his captor, SA Weekend, July 21, 2017

Roland Carter set off from his lands around South Australia’s Lake Alexandrina to fight the Germans in WWI, the first Ngarrindjeri man to enlist. He could never have expected the remarkable journey to come, or that he would find among the enemy a man he would come to call his “dear friend” – whose influence would extend even beyond both their deaths.

An estimated 1500 Aborigines served on the Western Front in the Australian Imperial Force in WWI, but Roland turned out to be of special interest to the Germans.

Some of his story has been told by the SA Museum in an exhibition Aboriginal Anzacs: From South Australia to the Great War. But continuing research by the Australian War Memorial is fleshing out his extraordinary story.

Before the war, Roland worked as a labourer. He was the first Ngarrindjeri to enlist from the Point McLeay Mission Station (now Raukkan). In all, 20 per cent of the indigenous men from the district enlisted.

In September 1915 Roland sailed for Egypt, part of a reinforcement group for the 10th Battalion expecting to take on “Johnny Turk”. Instead, he was transferred to the 50th Battalion and sent to the Western Front.

In August and September 1916 he fought at Mouquet Farm, part of the Battle of the Somme, and was wounded in action. Back in the field on April 2, 1917, 100 years ago, he was part of the 50th Battalion’s assault on the village of Noreuil.

That day in April the Germans were retreating to the Hindenburg Line, leaving Noreuil among a number of fortified villages aimed at slowing the Allied advance.

The 50th were expecting a mopping up exercise and simply didn’t have sufficient resources when they came under heavy fire. Eighty of their men were captured. Roland had been shot in the shoulder and was among them.

He was treated at a German field hospital before being sent to a hospital at Zerbst, near the Elbe River in Germany. By November 1917 he was in a PoW camp at Wundsdorf-Zossen just south of Berlin.

We know a lot of the detail because Roland’s mother, Rose Carter, was one of those who used the services of the Red Cross in Adelaide to keep track of her son. He wrote to her in September 1915 that he was in hospital in the Middle East with a skin complaint, but she heard no more, so in May 1916, fearing he had died, she wrote to the Red Cross.

The SA branch of the Red Cross was autonomous in World War I, and its archives ended up in the State Library of SA, giving South Australians a unique insight into the fate of their First World War soldiers not afforded to anyone else in the world.

The slow and painfully bureaucratic process of the Red Cross writing letters in duplicate to the AIF, and the replies finally let Rose know that her son was alive and well with the Mediterranean Forces. The Red Cross also notified her when he went missing at Noreuil and when news came that he was a PoW in hospital at Zerbst.

A postcard written by Roland and dated October 10, 1917, was sent from Zerbst and relayed to Rose by February, 1918: “I am not in the best of health,” wrote Roland. “my wounds have all broken out again, but I hope to be better soon. I am attending the doctor — I am getting good treatment here. All my other comrades are in the best of health.”

By the time Rose saw a copy of that card, Roland was in the PoW camp called Halbmondlager, German for “crescent moon camp”. Now this was a very unusual camp. It was probably the least unpleasant of the 172 PoW camps in Germany. Aaron Pegram, a senior historian at the Military History Section of the Australian War Memorial, has been investigating the Halbmondlager and its population of prisoners from many corners of the globe, including Roland.

The camp had been established in 1915, and, true to its name, included the first mosque to be built on German soil. The reason, at least ostensibly, was to take Allied forces’ Muslim PoWs and treat them well in order to convince them to return to the battlefield to carry out jihad against their French and British colonial masters.

By 1916, there were 4500 Muslims in the camp. They were part of the British colonial troops from India and Egypt, and from French North Africa. Another camp contained Russian Muslim PoWs.

They were pawns in a game dreamt up by a German diplomat who had been in Cairo before the war. Max von Oppenheim had become Germany’s expert on the Middle East and argued that, when Muslim Turkey joined the conflict, Muslim colonial soldiers could be persuaded to fight the British, French and Russians in a holy war.

About 3000 Muslim soldiers were recruited but the experiment was a failure. A victim of his inclination to stereotype all Muslims as potential jihadists, Oppenheim had misjudged their enthusiasm for his plans. Attempts to persuade Irish soldiers to swap sides brought similarly poor results. The Halbmondlager ended up with a wide cross section of the world’s population. There were Hindus, Sikhs, West Indians, Algerians, Senegalese, Newfoundlanders, Chinese and many others.

There were also two Aborigines, Roland Carter and Douglas Grant. Unlike Roland, who had a traditional upbringing and could discuss indigenous healing techniques with his doctors, Douglas was city-raised. He was survivor of a massacre in southwest Queensland. He was found by a member of an Australian Museum collecting expedition and adopted. His upbringing, with his white foster brother included being educated in Sydney, working as a draftsman, and becoming an exceptional player of the bagpipes – his adoptive father was of Scottish extraction.

Pegram says that by 1918 scholars from nearby Berlin were visiting the PoW camp because of the opportunities it gave them to study the diverse population there. They were supported by photographers and artists.

In the 1980s German research worker Margot Kahleyss found a box of 136 untitled glass slides at the Museum of European Cultures, Berlin. After a lot of detective work she was able to identify them as images of non-European prisoners of World War I taken by architect and keen photographer Otto Stiehl. The photographs, which are excellent portraits rather than the blank documentary photographs typical of the era, include the two Aborigines, Roland Carter and Douglas Grant.

Another image from that PoW camp at that time is a portrait painting by German artist Thomas Baumgartner.

The portrait has recently received national publicity as the Victorian War Remembrance Committee try to discover the identity of the sitter. There is a strong case for it being of Roland Carter, although confirmation may be very difficult and the location of the original painting is unknown. The image of a tousle-haired and bearded PoW contrasts strongly with Stiehl’s photograph of the spruced up Roland in uniform.

Among the researchers measuring craniums, eyes, noses, heights, taking the phonographic recordings and photographs was Leonhard Adam, an anthropologist who got to know Roland and Douglas.

While Douglas, like Roland, was photographed and measured he was disregarded for ethnographic study by Leonhard because his Sydney upbringing meant there was little to learn from him. But Leonhard was much more interested in Roland and the two became friends.

The prisoners were well treated at Halbmondlager. Leonhard recalled that Roland liked to play football, while Douglas preferred to read Shakespeare.

In a letter sent through the Red Cross to Rose, and dated March, 1918, Roland said how much he enjoyed going to church service, and how he had been given parole if he promised not to escape.

“I went in the town to see the moving pictures,” he wrote. “All the Native prisoners of war went.”

After Armistice in November, 1918, Roland was sent to England before returning to Australia, and being discharged from the AIF. He returned to live among his Ngarrindjeri people at Lake Alexandrina.

But his connection with Leonhard Adam was not yet over. The Berlin-born Leonhard was 27 when he first met Roland. He was a student at the Royal Frederick William College and the Ethnological Museum. He studied ethnology, law, economics and Sinology at the University of Berlin before graduating in law in 1916 from the University of Greifswald.

Leonhard’s passion was for ethnology, leading to his study of Roland Carter. After the war he qualified to practise law in Berlin. He was appointed an assistant judge and later a district court judge.

His interest in Roland, and other inmates in German PoW camps was because of his research into “primitive” law. He wrote articles and lectured in primitive law and ethnology at the Institute of International Law, and was a member of a board of experts at Berlin’s Ethnology Museum from 1931.

The only impediment to Leonhard’s continued rise in Berlin society was his heritage. He was part Jewish.

In 1933 the Nazis took power and stripped him of all his positions. As the situation for those of Jewish extraction worsened, Leonhard was able to escape, and in 1938 sought refuge in the UK. At first, things went well, and he taught at the University of London and wrote articles on ethnology, but in 1940, because of Britain’s paranoia following its retreat from France, he was interned as an “enemy alien”. The irony of his situation must have been devastating, particularly when he thought of his conversations with Roland, 22 years earlier.

He was sent off to Australia on the Dunera, and ended up in an internment camp at Tatura in Victoria. There, he continued to lecture in ethnography and art, one of so many deported and interned gifted scholars that he was elected pro-rector of their “Collegium Taturensae”.

Within two years he had been released and given a position at Queen’s College, University of Melbourne, and had begun to research the Aboriginals’ use of stone.

He married pianist Julia Baillie in 1943 and rose to the position of lecturer, but was always frustrated by Australia’s lack of interest in the discipline of anthropology. He was naturalised as an Australian. In 1957 he returned to Germany to be awarded a doctorate from the University of Bonn.

He died in Bonn in 1960 of a heart attack during a second visit to Europe for an anthropology conference in Paris.

But back in 1947, Leonhard had learned that his former “subject”, Roland Carter, was alive and well at Point McLeay. He persuaded Baillie’s sister Helen to visit Point McLeay. There, she met Roland’s family and spent the night at the mission. Roland wrote a letter to Leonhard, saying he would love to visit him, but his War Pension did not stretch that far.

Read more (may involve paywall)

*Peter Monteath is a professor of history at Flinders University