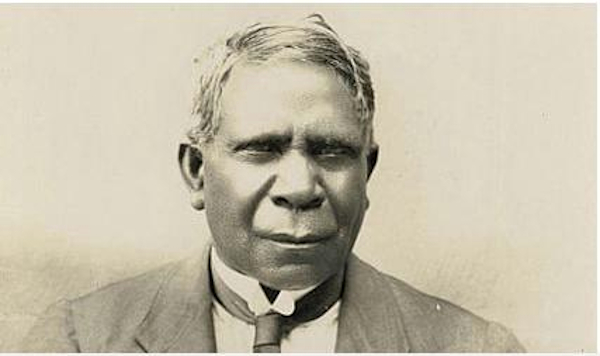

Banner: Portrait of David Unaipon on the $A50 note/ Getty Images

Professor Barry Judd, Dr Rachel Standfield, Dr Katherine Ellinghaus, Unaipon: Behind the Da Vinci comparisons, The University of Melbourne, 3 August 2020

David Unaipon has been transformed into the Aboriginal polymath. Yet what do these comparisons with da Vinci mean when considered against the backdrop of settler-colonialism?

Since the late 1980s the reputation and legacy of David Unaipon (1870-1967) has undergone a transformation, culminating in his likeness appearing on the current Australian fifty-dollar bill from 1995.

During his lifetime, Unaipon also enjoyed a degree of fame as an Aboriginal person of note. A Ngarrindjeri man of the Coorong region of South Australia, Unaipon was born at Point Mcleay Mission. At an early age he was identified as an outstanding schoolboy learner.

His academic abilities made him the focus of mission education with Unaipon becoming widely viewed by the missionaries as exceptional among the Ngarrindjeri. At the age of thirteen he became house servant to C.B. Young of the Aborigines ‘Friends’ Association in Adelaide.

Here he was encouraged to study literature, music and science. Despite this period of sustained learning, at the age of 20 Unaipon returned to Port McLeay where he was apprenticed to a boot maker and became church organist and bookkeeper to the mission.

UNAIPON’S FAME

Despite his lowly occupational pursuits, Unaipon arguably became the most famous Aboriginal person in the world during the period between Australian federation and the outbreak of World War Two.

His fame was built on a tireless and lifelong commitment to the pursuit of knowledge.

Unaipon engaged with science as an inventor of machines, with the social sciences and humanities as an author of literary and ethnographic works, and with the history and philosophy of religion through the many lectures he gave as a travelling preacher.

In science he laboured to unlock the secrets of perpetual motion in a search that lasted into old age. Drawing on the aerodynamic qualities of the boomerang, he also proposed a vertical lift flying machine a decade and a half prior to the invention of the helicopter.

Most famously, Unaipon invented a mechanism that transforms circular to linear motion – a discovery that underpinned the development of the modern sheep shears.

Patent specification. Mechanical motion. Sheep shears. No. 15,624, 1909. D. Unaipon, SA. Picture: State Library South Australia

As a writer, Unaipon became the first noted Aboriginal storyteller to harness the English language in its literary form to communicate aspects of the law and culture his Elders had taught him, bringing it to a national and international audience.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s he regularly authored pieces for the Sydney Daily Telegraph and published booklets on a range of topics that addressed science, literature and ethnography.

Among his writings the most well-known is ‘Myths and Legends of the Australian Aboriginals’, first published in 1930. It is remembered as the first monograph to be authored by an Aboriginal person.

REVIVING UNAIPON’S LEGACY

As an inventor and author Unaipon was never rewarded with commercial success. In science he lacked the finances to protect his inventions with full patents. His writings were plagiarised by the naturalist and anthropologist Professor W. Ramsay Smith.

Recent attempts to revive the memory of Unaipon have rightly focussed on his scientific and literary endeavours to provide long overdue national recognition and acknowledgement for his various contributions to Australia.

The work of scholars Adam Shoemaker and Stephen Muecke to republish Unaipon’s book under his name and to institute a literary award for Indigenous writings in his honour proved a turning point in bringing his lifetime achievements to a contemporary national audience.

More recently, others in academy have evoked the memory of Unaipon to encourage greater Indigenous student engagement with STEM programs.

The focus on his scientific and literary achievements has witnessed Unaipon being uncritically remembered as Australia’s answer to Leonardo da Vinci (we should note too that da Vinci is also being re-examined).

COMPARISONS WITH DA VINCI

Unaipon has been transformed into the Aboriginal polymath – an Aboriginal genius, the man on the fifty-dollar bill. Yet what do these comparisons with da Vinci really mean, particularly when considered against the backdrop of settler-colonialism, a legacy that infects and corrodes all aspects of Australia’s national past?

What many recent revisions of Unaipon don’t draw attention to is his unwavering advocacy of Christianity – a religious commitment that motivated his work in both the sphere of science and the literary arts.

We remember Unaipon as a da Vinci-like renaissance man, an exceptional genius who stands apart from the normative and persistent settler-colonial stereotypes of Aboriginal intellectual deficit.

Yet throughout his writings and speeches to church groups and others Unaipon consistently argued against the view that he was an exception in respect to the general intelligence he believed existed amongst the Ngarrindjeri and all other Aboriginal peoples.

‘“I was always interested in inventing,”’ Unaipon is quoted as saying in a 1914 interview published in Lone Hand, adding as though unwilling to appear in any way exceptional, “as are most aboriginals.”’

Through his writings on the religious beliefs of his people, Unaipon made it clear that he believed Aboriginal peoples held moral equivalency with the settler-colonists. He believed that nurture and not nature was the only difference between white civilisation and black primitivism, as Niel Gunson noted.

RETHINKING NARRATIVES ABOUT UNAIPON

Unaipon’s conviction that he was ‘a fair sample’ of what can be accomplished if the aborigines are taken in hand when young sent a clear message to his contemporaries that it was justifiable to remove Aboriginal children from what was considered a degenerate environment.

To position Unaipon as genius not only reinforces ideas of his exceptionalism as an Aboriginal ‘native’ that he argued against all this life, but fails to unlock the coded arguments now widely discredited that he advocated with force during his time of fame and influence.

To compare him to da Vinci only works to place him into a victim narrative that emphasises his lack of recognition and recompense during his lifetime.

It also blindly follows the narrative set up by the assimilationists who as early as 1909 promoted him as ‘an aboriginal scientist and inventor’ or ‘Australia’s Cleverest Darkie’ or ‘a contradiction in human terms, An Australian native, who is a philosopher, inventor, and musician’.

Seeing Unaipon as comparable to da Vinci ignores the very particular cruelties of settler colonialism.

As we rethink the scientists and scientific ideas of the past, we can only truly understand figures like Unaipon by weaving together the humanities and sciences with Indigenous knowledges and perspectives.

The authors are members of a University of Melbourne-led cross-disciplinary research group investigating Turbulence. This project weaves together humanities and scientific approaches with Indigenous knowledges and perspectives.