Brandon Sward, Brazilian Conceptual Artist Steals Historic Coin From the British Museum, Hyperallergic, 12 July 2024

Ilê Sartuzi replaced a silver coin with a replica and deposited the original in a museum donation box in a commentary on cultural theft.

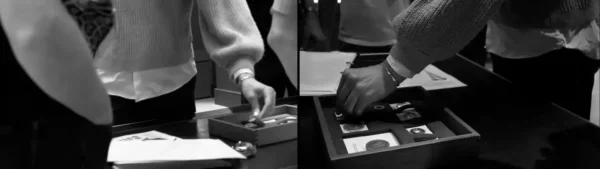

A little after noon on Tuesday, June 18, Brazilian artist Ilê Sartuzi entered Room 68 of the British Museum and secretly replaced a silver coin minted during the English Civil War with a replica. Sartuzi then left Room 68, walked downstairs, and deposited the real coin in the museum’s donation box. The action was the culmination of more than a year of preparation, involving legal consultation, study of architectural plans, and dozens of visits, all condensed into a single, split-second legerdemain.

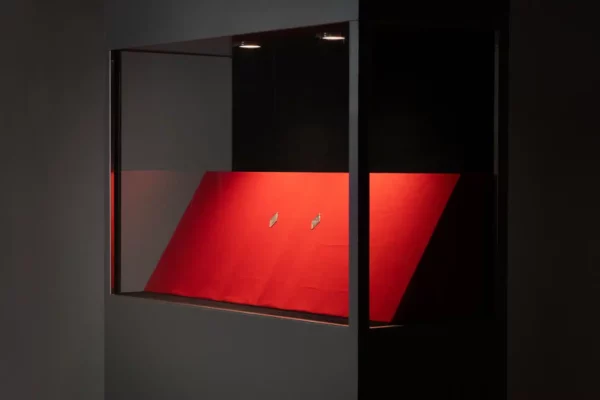

Titled “Sleight of Hand,” the project is part of Sartuzi’s MFA presentation at Goldsmiths, a constituent college of the University of London, and is on view through July 16 in the school’s Ben Pimlott Building. Through a two-channel video installation, museum display with two fake coins, and a text, the exhibition documents the theft and return of the object.

In response to Hyperallergic’s request for comment, a British Museum spokesperson characterized Sartuzi’s action as a “disappointing and derivative act that abuses a volunteer-led service aimed at giving visitors the opportunity to handle real items and engage with history.”

The coin was part of a group of objects reserved for educational purposes, including hands-on sessions with visitors.

“Services like this rely on a basic level of human decency and trust, and it would be a shame to have to review the provision of these services due to actions like this,” the spokesperson said, noting that the museum will be alerting police to the incident.

Sartuzi bases his defense on Section 11 of the Theft Act of 1968, which states that “any person who without lawful authority removes from the building or its grounds the whole or part of any article displayed” is guilty of an offense, and the British Museum’s policies, which state that visitors “must not touch any collection object on open display, including sculpture or stonework, except as part of our organised events, which include Touch tours and object handling desks.”

As Sartuzi’s interaction with the coin occurred in the context of one such “object handling desk,” and since he technically didn’t remove the object from the museum, Sartuzi and his lawyer argue that no laws or policies have been broken.

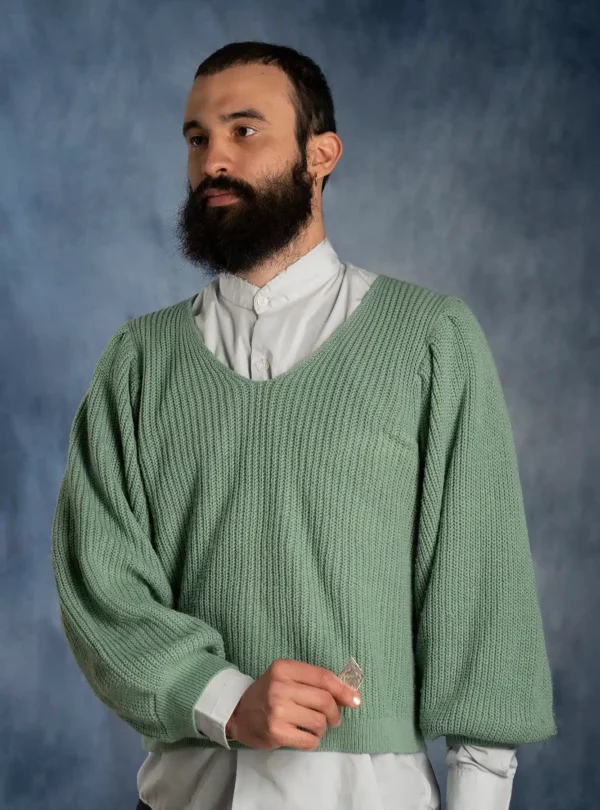

Sartuzi told Hyperallergic that he believes the work “opens a discussion around theft and looting in both a historical context and from a neocolonial perspective within contemporary cultural institutions,” observing, for instance, how the 1911 theft of the Mona Lisa exponentially increased the painting’s renown.

With a collection of over 8 million individual works, the British Museum describes itself as “the first museum to cover all fields of human knowledge.” However, it has been increasingly plagued by repatriation claims aimed at some of its most famous acquisitions, including the Rosetta Stone and the Parthenon Marbles. The government of the United Kingdom tasks the institution with telling “the story of human culture from its beginnings to the present.” To contemporary ears, the pretension of this mission is nothing short of breathtaking. How could such a grand responsibility fall to one institution? And how could such an amassing not prevent the ability of everyone else to tell their own stories?

Thematically, “Sleight of Hand” builds upon two of Sartuzi’s animating interests, theater and magic, both of which rely upon the “momentary suspension of disbelief,” as he says in a statement about the work. It is difficult for the audience to enjoy Hamlet unless they pretend that they’re in Denmark, or a card trick if they’re always peering up the magician’s sleeve.