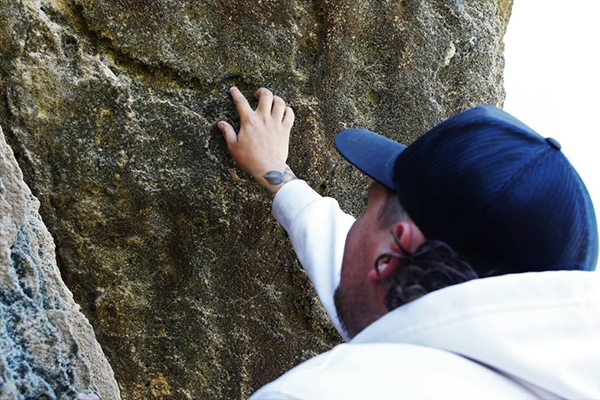

preminghana. Picture: Meg Powell

Meg Powell, Solid rocks, sacred ground: the story of preminghana and the return of ancient petroglyphs, The Advocate, 22 November 2020

At the end of a long dirt road, winding through kilometres of scrubby, blustery land on the far North-West Coast, lies one of Tasmania’s “worst kept secrets”.

Jutting out of the edge of a grassy coastline is an ancient rock. Its deeply pocked face overlooks the Southern Ocean, solid and constant for thousands of years.

The rock is the only visible remnant of a deep scar in the landscape.

Bathed in sunshine, the unique coastline bears little visual evidence of a “great wrong” carried out nearly 60 years ago – when a group of workers hacked ancient Aboriginal carvings out of the rock face and dragged them hundreds of kilometres by bullock into the keeping of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery.

But, for many Tasmanian Aboriginal people who still live, love and work on the land, the pain remains.

SACRED LAND

In 1995, the Tasmanian government made the landmark decision to hand back 13 parcels of land to the Aboriginal community, including a 540-hectare block tucked alongside Woolnorth, Tasmania’s most northwestern tip.

The land – formerly known as Mount Cameron West – is called preminghana, and is the original location of some of the most significant ancient rock engravings in the world.

Brendan Lowery is a proud palawa man, and the official caretaker of preminghana.

“I used to work in forestry, I can look out there and tell you every edible plant and name all the plants out there and tell you what they can be used for,” he said, driving through the scrubby, wild area.

“I’ve been doing some burning over there, weed management. There isn’t much of this area that I haven’t walked.”

Mr Lowery is fairly new to the job, having taken it over from his younger brother Timothy less than two years ago.

“I’m the green thumb, he’s the mechanic,” he said, pointing to his younger brother.

“I’m still learning all the palawa names for things. I had a pretty rough upbringing … I never finished school. But I’ve got an education from being on the land.”

Between them, the brothers have transformed much of the land, reversing the effect of years of grazing by Van Diemen’s Land Company, as well as removing tonnes of gorse and other invasive species.

For both brothers, managing and caring for the land has helped them connect with their ancestors, as well as reinforced a desire to get the petroglyphs back “where they belong”.

“I believe in the spiritual side of things,” Timothy Lowery said.

“I think our old people, they still watch over us… and it would be sort of calming for them to put it back.”

Brendan Lowery said he felt incomplete with the petroglyphs missing.

“There’s a lot of meaning behind the carvings,” he said.

“They would have represented the old people in their passings, big events. These days would it be acceptable to walk into someone’s grave and take a plaque for instance? It would be wrong to do that.

“When they taken that, they taken a part of us, a part of who we are. I don’t feel like my full self until it’s there. It’s just a part of me, it’s something you can’t really explain.”

THE JOURNEY HOME

Andry Sculthorpe works for the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre in Hobart, where he oversees a variety of heritage and land management projects.

“The community has been trying to get those petroglyphs back since … well, I remember since the 1990s,” he says, standing on a bright stretch of sand between turquoise ocean and a scrubby hill.

Before him is a small group of elders and local Aboriginal people, gathered at preminghana for NAIDOC Week.

He points to a rock – the last visible section of the carvings – behind him. The exact location is protected due to the highly sensitive nature of the area.

“A lot of rock carvings along the West Coast have similar stories and themes, but this one is unique in what’s known because of the amount of work that’s gone into it and the scale of it,” he said.

“At the moment we can’t actually see most of it, most of the carving is under the sand here.

“In the 1960s you could come here … it was all exposed and all revealed. You could see rock carvings that covered all this area.”

He said the Aboriginal community’s desire to see the carvings returned had been met with resistance for many years, fuelled in part by “fear”.

“For some reason, there seems to be a backlash against the idea that aboriginal people can own things,” he said.

“People understand national parks with all their restrictions and limitations. People understand private lands that you have to respect and not go on and do the right thing.

“In the positive sense, we’re also seeing support around the return of cultural objects and protection of heritage in this area.”

Last year, the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery promised to return the giant stones to the Aboriginal community, saying it was not “in line with current collecting practices”.

On November 11 this year, Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Roger Jaensch signed Aboriginal heritage permits for the return.

The arrangements for the physical return now lie within the responsibility of TMAG, QVMAG and the Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania.

Mr Sculthorpe said the “battle” had been long and constant.

“I can’t see any other possible outcome other than the wishes of the Aboriginal community to be fulfilled, but it’s really disappointing that the community has to continually fight these battles over basic rights,” he said.

He said a future challenge would lie in the protection of the carvings, and the balance between maintaining the Aboriginal community’s right to its own heritage as well as a desire to share it with the rest of the world.

“The community has aspirations to welcome non aboriginal people, mainstream society onto the land, to share the things that it’s proud of and that are meaningful to them,” he said.

“But it needs to be done in a structured and controlled way. So it’s unlikely that for such sensitive places it will be public access. But it is likely that there will be structured interpretation around these.

“In the end … it’s about the country, it’s about the landscape, it’s about the people and their connection and their sense of wellbeing.

“The aboriginal community is wanting to share what it had … but it has to do it on its own terms.”