Cassandra Bahr, A life through boxes: The collected archives of Jonathan Mane-Wheoki, Te Papa Blog, 11 June 2025

Humanities Technician Cassandra Bahr has been working in the Collected Archives at Te Papa, cataloguing and rehousing papers from people connected to Te Papa’s collecting areas. Her first task was working with the papers of Jonathan Mane-Wheoki, former Head of Arts and Visual Culture at Te Papa.

A previous blog post by Ruby Abraham, Meeting a man I will never know, perfectly describes working with Jonathan’s papers. I’ve just spent a few weeks continuing her work, and would like to echo her thoughts on how special it feels to get to know Jonathan so well through his papers. It feels like a real privilege to see such a range of texts from a person’s life – from his private life, to academic, to a public figure and esteemed art historian. Furthermore, his letters and essays are a pleasure to read and have inspired me to focus on my written correspondence (and to turn off auto-complete!).

Instead of completely copying Ruby’s blog, here’s a small selection of what I’ve learned from his letters, essays, newspaper clippings, postcards, and pamphlets.

Ostensibly, I was cataloguing and rehousing these papers, but I couldn’t resist reading some of them, especially Jonathan’s essays and letters. His writing is so eloquent and articulate, and always expresses personality and feeling. He is also quietly persistent in using te reo Māori greetings and sign-offs in his correspondence, even in the 1980s.

Art Academic

He has given me a new appreciation for art history, especially understanding the connections between art and politics. Art history is rarely taught at schools or universities these days (it was dropped from Otago University while I was a student there) but Jonathan’s work has reminded me what a powerful lens it is for understanding history and politics.

I found much to think about in his definitions of biculturalism, and realised how far we’ve come in terms of te ao Māori in mainstream Aotearoa. Jonathan discusses biculturalism in many of his papers, and also highlights the connection between monoculturalism and monolingualism. In one paper, he relates a meeting with Kanak chiefs in New Caledonia who asked if, as a bicultural nation, New Zealanders were also all bilingual.

“Official biculturalism […] springs from obscenely unequal power relations. On both sides of the Treaty partnership – that is, between Māori and the Crown – biculturalism is compulsory. On the part of the dominant culture it is optional. Thus we have an unbearable tension between the moral weight of the Treaty for Māori and the sheer force of numbers, the tyranny of the Pākehā majority. […] Biculturalism is usually assumed to refer to ongoing parallel relationship between Māori and Pākehā. Before it is that, however, it is a principle: it is the ability to move some way into the culture of another people from the security of one’s own culture. In the New Zealand context, Chinese, Korean, Japanese and other New Zealanders whose first language is not English, whose culture is not European or western, are compulsorily bicultural. In this equation, Pākehā are not.”

from “Critical interpretations of the arts curriculum”, 2002, by Jonathan Mane-Wheoki. Te Papa (CA001378/003/0006)

Jonathan’s work was integral in the inclusion of Māori art and architecture as art and architecture, which previously had only been treated as artefacts. He worked on the recently published Toi Te Mana: An Indigenous History of Māori Art . He also considered Indigenous rights outside of Aotearoa New Zealand, criticising an Australian art history conference that excluded Indigenous Australian art.

Collaboration and community

Jonathan seems to have had correspondence with every major and minor figure connected to the New Zealand art world in his lifetime, in addition to many other domains. He sat on many boards (such as the Māori Arts Board, the Arts Council of CNZ, the International Council of the Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Centre in New Caledonia, Te Whainga Aronui/Council for the Humanities… the list goes on), he supported local festivals, and was deeply involved with the Anglican Church, especially All Saints in London, and St Michael and All Angels in Christchurch. As well as this, there are, of course, all his students, including Te Papa Curator History Claire Regnault!

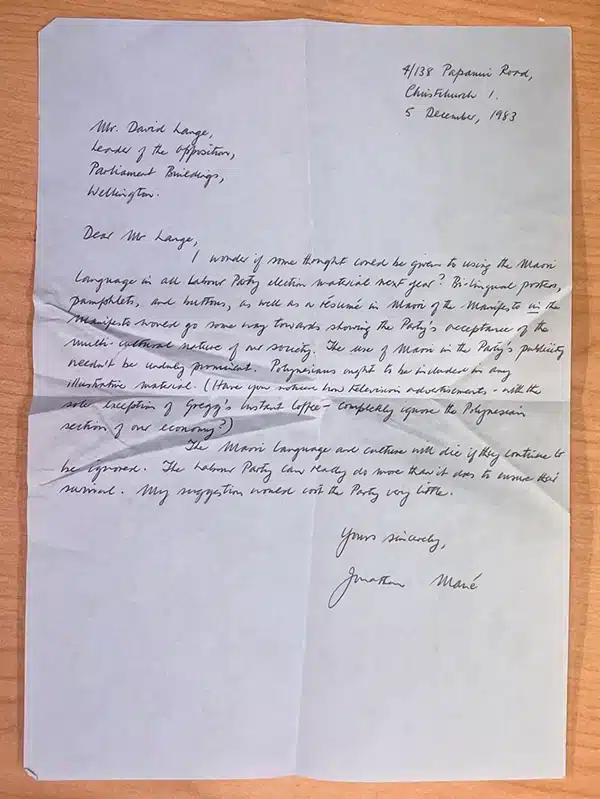

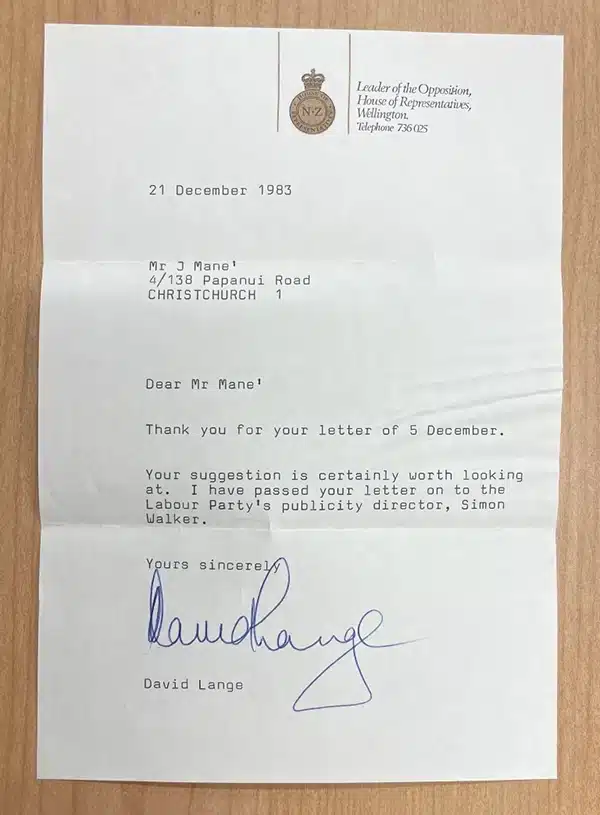

As a post-grad student in London, he was confident in submitting formal complaints to both the Police and the London Buses. In New Zealand, he wrote to David Lange advising more use of te reo Māori in the upcoming 1984 election campaign.

Finally, everyone in Aotearoa knows there’s never more than two degrees of separation between us all. My favourite connection I’ve found to Jonathan is that as a student at Canterbury, he sang in concerts with a singing teacher of mine (the incredible Judy Bellingham), who was also a student then.