Lucy Schrader, Museology, Myosotis, and metadata oh my! Sharing sustainably in Wikipedia, Te Papa Blog, 28 November 2022

Museology, Myosotis, and metadata oh my! Sharing sustainably in Wikipedia.

We generate a lot of data at Te Papa. Specimens. Photographs. Facts and figures. We’re always thinking of ways to get that data out there and into your hands – and recently we’ve been diving headfirst into Wikipedia. Here, Digital Channels Outreach Manager Lucy Schrader talks about the work that went into getting hundreds of images of forget-me-nots onto the site, allowing them to spread across the web.

Wikipedia is a little more unforgettable

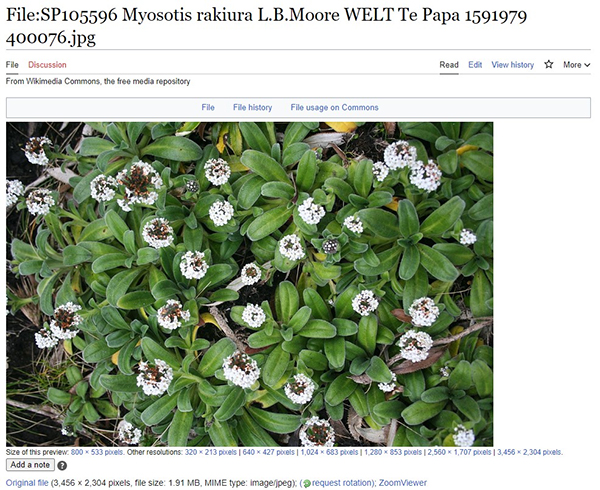

We’ve just completed our project to load 350 images of New Zealand forget-me-nots (native examples of the prolific Myosotis genus) to Wikimedia Commons! These beautiful and detailed images can now illustrate new and expanded articles on everyone’s favourite reference site.

These field, herbarium sheet, and pollen images show the detail and context of the plants, making it easier to identify and understand them. As they’re added to articles, they’re also getting circulated to sites like iNaturalist and in Google search results.

This was a trial run to understand the Wiki ecosystem better, and see how we might be able to contribute effectively and sustainably. We learned a lot, which we can now put into practice in our various collection areas.

The process got a little complicated, which is why I’m writing this post now. If you’re interested in doing a project like this, hopefully the tools and processes below will make things easier for you.

So what did we need to do?

In short, we had to:

- select the specimens we wanted to focus on

- select the right images to upload

- create a suitable data model for both descriptive and structured metadata

- export and transform our source data to work with Wikimedia Commons and Wikidata

- get everything ready in OpenRefine

- and load up the selected images and data.

The full details of what we did, including how we made decisions and where we ended up, are over on our Myosotis project Wikipedia:GLAM page.

First, find and pluck your wildflowers

Going into this project we knew we’d be working on Myosotis specimens – Botany curator Heidi Meudt had already been working on Wikipedia articles for several species as part of her decade-long taxonomic review of the genus, so it made sense to borrow her knowledge and enthusiasm, and use this project to support work already happening.

But Te Papa has a lot of plants, and for Myosotis that came to over 1,800 specimens with almost 9,000 images. We wanted to narrow that down because we were going to test OpenRefine’s bulk image upload functionality – an experimental feature that (for now) was more suitable with sets of 500 images or so.

The size of the set also mattered because of our intention to dig deep, rather than wide. A lot of institutions have large quantities of their collections loaded (shout out to Auckland Museum, who we got some great help from!), but they don’t come with a lot of metadata. Shrinking the set let us concentrate on all the juicy details we hold about these specimens.

Linking data, entwining root systems

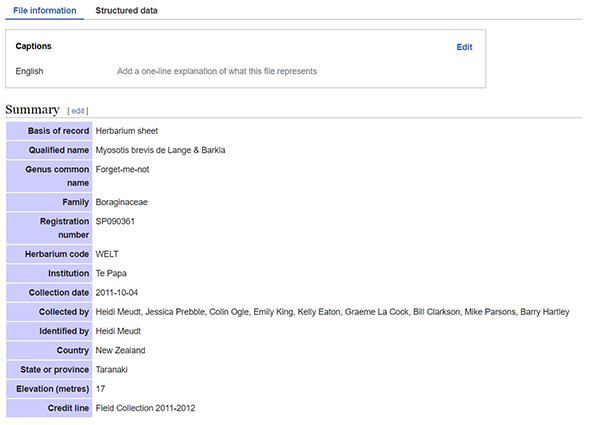

Images loaded to Wikimedia Commons don’t strictly speaking need a whole lot of metadata – just a filename, copyright statement, and maybe a short description. We wanted to go a long way beyond that, accompanying our images with a decent chunk of the rich information added by collectors, curators, collection managers… After all, we’re a museum, and we should be museological about how we share our material.

This is where things got pretty tough. Wikipedia and its related projects have matured a lot in how their tools and processes handle the humanities, but the natural sciences aren’t quite there.

Templates and structured data modelling for artworks, for example, are in pretty good shape, and well documented. However, the base Specimen template didn’t suit our needs, and even Naturalis’ comprehensive Biohist template wasn’t quite right.

To share exactly the information we wanted to share in the way that made sense for a national museum in Aotearoa, we created our own TePapaColl template, which we’ll be adding to and refining as we go.

Along similar lines, we plan to create a natural science structured data model page similar to the visual art one, using our botanical work as a starting point.

Next, spruce up the structured data garden with OpenRefine

It also turned out not a lot of people have used OpenRefine to load natural science specimens yet, which meant that not a lot of people have used Wikidata’s structured data with specimen uploads either, making us (anxious, but enthusiastic) trailblazers.

OpenRefine mattered to us for two major parts of the project:

- hooking up our source data to Wikidata statements

- loading the images and data together in a nice clean package.

(It was also extremely useful earlier on for viewing exported data, faceting and filtering down as we made our selections – can recommend! OpenRefine has really good documentation that’ll get you going.)

What is Wikidata? – Library Carpentry

With few examples of other specimen images that had been associated with Wikidata, we had to decide for ourselves which were the right items, properties, and statements. We hunted around, including reviewing the list of properties associated with biology.

Our final schema was not nearly that long, sticking with the what, who, where that contextualises an object. For example:

Finally, plant for next season

Though currently running on the adrenaline of success, we’ve still got heaps to learn. Aside from cleaning up, optimising, and repeating what we’ve already done, I’m eager to find out what we could do better and what possibilities this museum should be investigating.

If you spot me on Wiki talk pages, Mastodon, Telegram groups or anywhere else, say hi and please share your feedback! Plus, I’m always available at [email protected].