Julie and John, 1970s, by Spencer Digby studio, Digby / Ronald D Woolf Collection, Gift of Ronald Woolf, 1975, Te Papa.

Andre Chumko, Photographs of Aotearoa’s bold and beautiful to be digitised, Stuff, 18 September 2021

A huge collection of 250,000 images shot between the 1930s and 1980s is set to be digitised by the country’s national museum after an almost million-dollar lotteries grant helped fund the project.

Te Papa recently received $777,000 from Lotteries NZ to preserve and digitise the Spencer Digby–Ronald Woolf photo archive, a collection the museum has held for decades but has never processed in its entirety due to its scale. Once digitised, the collection will be publicly available. Already about 1380 images are online.

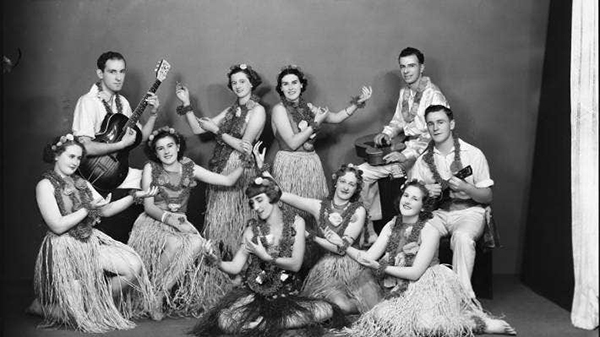

The images feature former prime ministers, World War II soldiers, operatic divas, authors, as well as bar mitzvahs, weddings, graduations and other significant community group events around Wellington.

Among those pictured in the collection are former prime ministers Michael Joseph Savage, Peter Fraser and Walter Nash; opera singers Kiri Te Kanawa and Malvina Major; broadcasters Maud Basham and Selwyn Toogood; and authors Robin Hyde and Ngaio Marsh.

“When it first came into the museum I remember the stacks of negatives went from floor to ceiling. The alternative was they were dumped. … One day I hoped we might have the resource to deal with it,” Athol McCredie, Te Papa’s photography curator, said.

With the funding, a team of specialists will catalogue, image, and re-house many of the negatives into acid-free envelopes. Technicians will also work to process the images through new scanning equipment, and McCredie hopes to get a photographic conservator to handle some 4000 flammable cellulose nitrate negatives which are highly unstable and explosive.

Te Papa was about halfway through digitising its total photography collections, and work on the Digby-Woolf lot would allow it to make more solid inroads, McCredie said.

Born in Essex in England and having trained as a photographer in London, Spencer Digby emigrated to Aotearoa in 1923 to accept a job from an Auckland photographic firm. By 1932 he moved to Wellington to start his own business, primarily taking high-quality portraits of Wellington’s high society out of his studio based in Lambton Quay’s Prudential Assurance Building.

Mrs D. Ying family, 1950, by Spencer Digby studio.

Ronald Woolf and his wife Inge, who were already working out of Kilbirnie, purchased the studio off Digby about 1960 and continued to operate it under Digby’s name, but with Woolf now taking photographs. Under his and Inge’s lead, its subject matter broadened to on-location photography and events, including things like father-daughter evenings at Erskine College, Greek balls, a Highland pipe band championship and the Accountants’ Society graduation celebrations.

DIGBY / RONALD D WOOLF COLLECTION, GIFT OF RONALD WOOLF, 1975, TE PAPA

Selwyn Toogood and unknown woman from a theatre production, 1937, by Spencer Digby studio.

The business later re-branded when it was taken over by Simon, Ronald and Inge’s son. Under Digby and the Woolfs, the studio had a high reputation locally and nationally, McCredie says, being used by the capital’s elite. “It’s important this material doesn’t get lost.”

When in charge, Ronald Woolf began using roll film versus formal sheet film, and oversaw a major shift to outdoor settings and the use of photo-decor, compared with Digby’s mostly-indoor portraits. By the 1970s, the idea of an upper-class society was almost gone, McCredie says, hence the upswing in regular Wellingtonians whose images featured in the collection after Woolf took over.

Untitled (double exposure portrait of Gordon Purdie), 1977, by Ronald Woolf.

While colour slide film came into force in the mid-1930s, it was not used professionally, so much of Digby’s work is black-and-white or hand-painted with watercolours. In the studio’s Woolf era, colour printing was available.

McCredie says the collection represents a fascinated visual record of life in the capital. “It’s things you can’t do with cellphones – lighting, conventions, techniques. It created a richness about photographs that you don’t see today. I guess that’s why people went to them.

Chinese wedding couple, 1970s, by Ronald Woolf.

“The number of images in the studio was indicative of how people wanted to be seen … You can really see the progress and reflection of society from pre-war through to the 1960s when things were much less formal.”

Digby was a cultured man who was in interested in classical music and theatre. This could be seen in his photographs, which had a smooth tonality about them. They speak to a time-gone-past, where many professional photographers had shop-front windows and showcased their work and wares to pedestrians. “That’s all gone now,” McCredie says.

Faith Panapa, circa 1970, by Ronald Woolf.

While professional photographers were still operating in 2021 working at events like weddings and doing some portrait work, many were operating from home, and not shooting in traditional studio spaces. A large part of that shift has been due to the explosion of technology, McCredie says, with most people having access to a camera via their cellphone, and the rise of selfies and Instagram making photography not as novel.

Once-omnipresent mobile portrait photographers, who would set up shop in department stores and supermarkets, were also now absent from everyday life.

Iris Wilkinson (Robin Hyde), 1936, by Spencer Digby studio.

Deborah Hart, Ronald Woolf’s daughter, said many Kiwis would get a kick out of seeing the collection digitised. Te Papa tended to get familial research enquiries–this would benefit all those people, she said.

Hart says her father had a long relationship with the former Dominion Museum (Te Papa), having often borrowed korowai and other taonga to photograph. It was this reason he wanted his negative file to be in its care. “He knew it was highly valuable in terms of history … It’s one of the largest and longest-running negative files in the country. To safeguard that was absolutely critical to him.”

Rosaleen Norris (nee Hickmott), circa 1948 by Spencer Digby studio.

When the immaculately kept record books of negatives were gifted, the family also gave over old enlargers, lighting equipment, photographic magazines, original photographic prints and a range of quarter-plate and full-plate cameras.

Digby died in June 1995. Peter Kitchin wrote in his obituary that Digby’s photographs “predated the work of public relations and grooming industries, which were later to mould politicians into photogenic celebrities”.

Self-portrait, 1966, by Ronald Woolf.

Ronald Woolf, who was a trained chemist and technician, died in 1987 in a helicopter crash. As well as honouring Digby and Woolf, the collection’s preservation acknowledges photographic pioneers like Brian Brake, who heavily contributed to the studio’s operation and worked alongside Digby.

Simon Woolf said there were about 33 photographic studios in the capital at the time of his father’s death. Of those, only two or three still exist. He still remembers modelling for his father, when he and his sister were children. One day the story may be worth a book, he said.

Simon and Deborah Woolf (Hart) in a tree, by Ronald Woolf.