Spectrogram print-outs of slowed-down songs of various cicada species in the Kikihia genus; cut out and arranged for comparison by Charles Fleming. Photo by Finlay Dempster. Te Papa.

Finlay Dempster, Sir Charles Fleming’s cicadas to soon sing again, Te Papa, 30 November 2021

Dr Julia Kasper, Lead Curator Invertebrates Entomology, recently rediscovered a box of audio tapes stored alongside our entomology collection. These audio tapes were recorded by Sir Charles Fleming in his pioneering study of our country’s cicadas in the 1960s and 70s. Finlay Dempster, one of our natural history interns, explains the significance of these audio tapes and the man who made them.

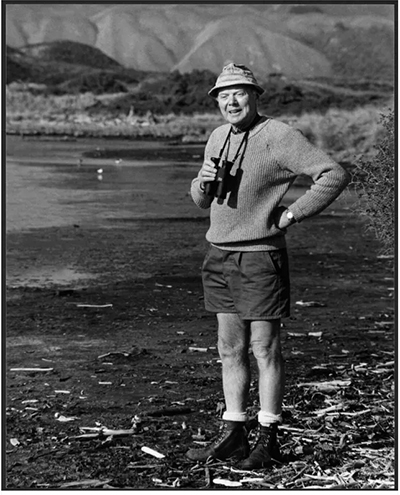

Sir Charles Fleming KBE, DSc, FRS, FRSNZ

Born in 1919, Fleming spent the majority of his career at the New Zealand Geological Survey (predecessor to GNS Science), eventually rising to Chief Palaeontologist. It is his knowledge of, and contribution to, New Zealand geology and palaeontology for which he is best known.

Birdlife and banding

However, Fleming was also a national expert on native birds and shells, his knowledge founded on a childhood spent birdwatching and beachcombing. He published scientific papers in these areas regularly, drawing on research done both professionally and in his spare time.

Most notable amongst these papers was the first significant study of the birds in the Chatham Islands. He pioneered the use of leg bands to identify individual birds when studying silvereyes in 1943 and was a founding member of the New Zealand Ornithological Society in 1940.

An ardent environmentalist, Fleming was involved in many important early environmental campaigns in New Zealand. In particular, he was a key member of the Save Manapouri Committee, which successfully opposed a governmental plan to dam Lake Manapouri. This proposal would have raised the lake by 30 metres, joining it with Lake Te Anau.

Fleming successfully lobbied for the creation of many nature reserves, saving large tracts of native bush from conversion to pine. His frequent talks and articles about environmental issues did much to inject environmental concerns into the public consciousness.

Charles and his cicada studies

It wasn’t until later in life that Fleming’s attention switched to insects. Cicadas piqued his interest when a colleague asked for assistance with his son’s school project on cicadas, and Fleming realised he knew little about the insects.

Fleming required specimens to study cicadas. Thus, cicada-collecting became his weekend activity of choice during the summer, along with his wife, Lady Margaret Fleming (who went by Peg), and their three children.

Cicada Task Force assemble!

Inconveniently, however, many cicada species are restricted to remote areas, meaning the Fleming family team of five needed help collecting specimens. Fleming used his annual Christmas cards, school newsletters, and talks to tramping clubs to enlist family and friends, school children, and trampers to collect cicadas for him. Specimens would arrive in matchboxes through the mail from all over the country.

With such a large task force involved, it is unsurprising Fleming amassed an impressive collection of several thousand cicada specimens. In keeping with his civic-mindedness, Fleming donated his cicada collection to the Dominion Museum (Te Papa’s predecessor) in instalments from 1970 until he died in 1987.

Reel-to-reel cicada songs

Fleming had a particular interest in cicada songs. Were songs wildly and randomly different from species to species? Or were there similarities in song structure among species within a genus?

If the answer to the latter question was ‘yes’, Fleming could use song structure to aid his taxonomic revision of New Zealand’s cicada species. This was a novel concept. Until then taxonomic study of cicadas had focussed on morphological features of cicadas (such as body patterning and genital shape).

Listen to this audio tape recording of three species of Kikihia cicadas, taken by Sir Charles Fleming, and recently digitised by Te Papa. You can read the transcript at the end of this post.*

Answering these questions required a large volume of cicada recordings – not an easy feat given the technology of the time. Fleming began recording in the field, lugging a filing-box-sized reel-to-reel recorder up mountains and down gullies. To eliminate interfering sounds (birds, wind, other insects) he later switched to capturing cicadas and recording their songs at home at the dinner table.

Whirrs, zees, and zits, and clicks

The cicada’s method of sound production is unique among insects. Most insects produce sound by rubbing their legs or wings together. Cicadas instead use a specialised organ called a tymbal. A tymbal is an exoskeletal (outside the skeleton) membrane. Each cicada has two tymbals; one tucked behind each set of wings.

The membrane buckles inwards when a specific muscle attached to the membrane is contracted. It is the buckling and subsequent release of the membrane that creates sound. The process is comparable to the popping sound created by pressing down on and releasing an unsealed jam jar lid. Cicadas buckle their tymbals hundreds of times per second.

The rapid speed tymbals operate at means individual clicks blur and blend together, creating the familiar summer chorus of whirrs, zees, and zits, but making it impossible for humans to hear individual clicks. Fleming, therefore, required a method of differentiating individual clicks.

Solving the speed issue of the cicada song

Fleming needed to study the song structure at an individual click level to answer his question of whether cicada songs could aid the taxonomic study of the cicada family. This is because species that are more closely related to each other are more likely to have similar underlying song structures than are more distantly related species.

He slowed his recordings down to 1/64th their natural speed which allowed him to analyse the different features of cicada songs.

His study was further aided by using dynamic spectrograms: visual representations of sounds, displaying audio frequency over time. These spectrograms were made in the physics laboratory at the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR), and were printed onto long rolls of 35mm film.

Conclusions on cicada songs

Fleming’s study of cicada songs culminated in a 1975 paper**, where he concluded: “each of the five cicada genera … has a distinctive acoustic behaviour pattern”.

Fleming concluded that the songs of species in the genera Kikihia, Rhodopsalta, Amphipsalta, and Notopsalta could each be reduced to a basic song structure.

But the songs of species in the Maoricicada genus were much more diverse, as shown by the differences between the Maoricicada species cassiope, mangu, and hamiltoni. This perhaps suggests a longer history of speciation in Maoricicada than in the other four genera.

The number of known cicada species in New Zealand nearly doubled to around 40 species during the 20 years Fleming worked on cicadas. In total, he discovered and described 16 cicada species, and his research remains the foundation of cicada studies in the country today.

The future will be digitised

What does the future hold for Fleming’s audio tapes, spectrograms, and prints? The digitised recordings will be stored in our media database, ensuring Fleming’s cicada recordings survive the physical audio tapes.

Our Entomology team hopes to use his recordings to kick-start a long-term goal of creating an online insect sound database for the public.

The spectrograms and prints will likewise be archived with us, preserving a small part of Sir Charles Fleming’s great scientific legacy well into the future.

Further information

More information about Sir Charles Fleming’s life can be found in his biography written by his daughter, Dr Mary McEwen, Charles Fleming: Environmental Patriot, Craig Potton Publishing, 2005.

If you’re in Wellington, you can find out more about endemic cicadas in Te Taiao | Nature on Level 2.

References

*Transcript of the audio file:

Transcript of first two minutes of Charles Fleming’s audio tape recording 3885A:

The New Zealand endemic cicada genus Amphipsalta is the only cicada group in the world which combines normal tymbal song with wing clapping that give periodic clicks. There are three species.

One: zelandica – extending throughout both main islands.

Another: cingulata – confined to the North Island.

And a third: strepitans – which spans Cook Strait – mainly in the northern part of the South Island, but crosses Cook Strait – so that there is a very small area in Wellington province where all three species occur together. They are separated, however, by the isolating mechanism of their songs.

Here is cingulata, the North Island species:

[Amphipsalta cingulata song plays]

Zelandica:

[Amphipsalta zelandica song plays]

Strepitans:

[Amphipsalta strepitans song plays]

[end]

** Fleming, C. A. (1975) Acoustic behaviour as a generic character in New Zealand cicadas (Hemiptera: Homoptera), Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 5:1, 47-64.

See also: Cicada fossils unearthed on a Central West NSW farm help shed light on Australia’s oldest ecosystems