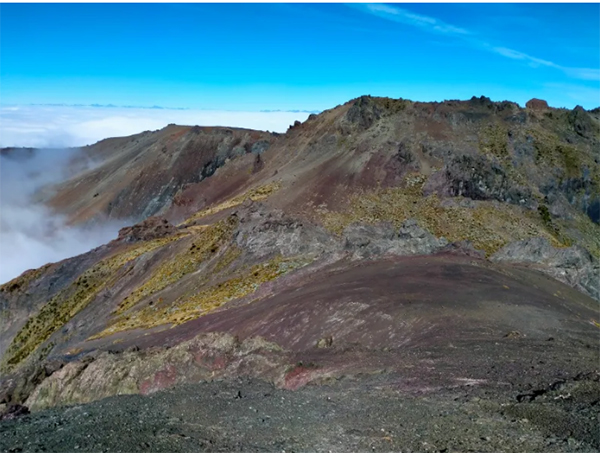

Panorama of the Acheron Lakes in the Livingstone Mountains, January 2022. Photo by Geoff Rogers.

Heidi Meudt, Botanising New Zealand’s southern ultramafic mountains in the South Island, Te Papa, 7 March 2022

Botanising New Zealand’s southern ultramafic mountains in the South Island

In January 2022, our Botany Curator Heidi Meudt went on a chock-a-block seven-day field trip to Southland with Department of Conservation botanist Brian Rance and several others. The aim of this trip was to collect several species of forget-me-nots growing in the ultramafic Livingstone Mountains and nearby hills. Heidi talks about what they were looking for and the environment the forget-me-nots were growing in.

What are ultramafic mountains?

Ultramafic mountains contain soils that are rich in iron and magnesium, have high concentrations of toxic heavy metals, and have low concentrations (or availability) of major plant macro-nutrients. Ultramafic mountains contain igneous ultramafic rocks, which were formed when hot, molten rock solidified.

In New Zealand, this molten rock was produced millions of years ago, as oceanic crust spewed out of a previous ridge separating tectonic plates, eventually forming a large ultramafic terrane on the boundary of the South Island Alpine Fault.

As a result, major ultramafic outcrops now occur in narrow belts which are offset along the Alpine Fault within Nelson-Marlborough and in south Westland-Southland. You can see these belts (dark brown areas labelled “Ymm”) as well as the ultramafic terrane remnants (the Dun Mountain Ophiolite Belt, brown areas) in this zoomable Geological map of New Zealand.

The Livingstone Mountains are in the heart of the southern South Island ultramafic belt. Even though they are considered to be ultramafic mountains, they are actually dominated by highly fractured volcanic rocks, whereas their ultramafic rocks form orogenic belts or are restricted to smaller outcrops that can be followed across the landscape. Such outcrops are one example of a number of naturally rare New Zealand ecosystems with ultramafic geology (Williams et. al, 2007).

Due to the oxidation of iron and magnesium, both ultramafic and volcanic rocks can be red or brown, and in the Livingstone Mountains we also saw some beautiful green volcanics mixed in.

Hitting the trifecta with an experienced team

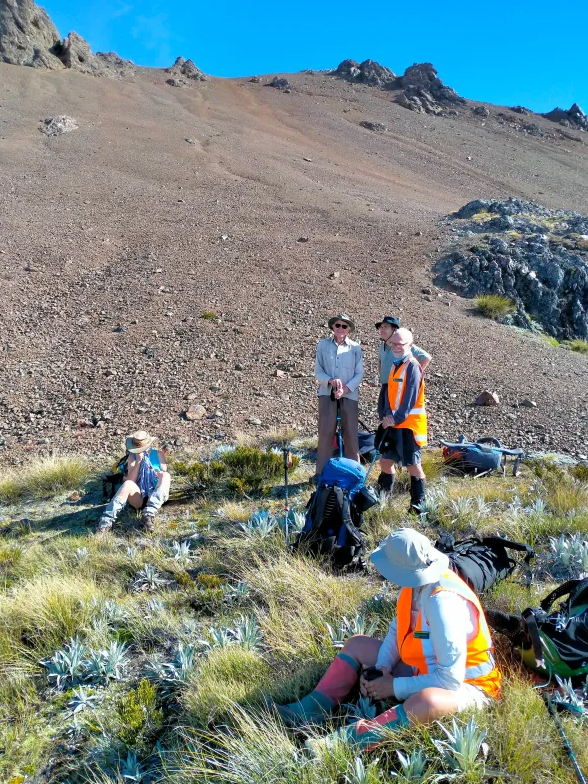

On this trip, I was extremely fortunate to be accompanied at all sites we visited by Brian Rance (ecologist at the Department of Conservation; DOC). But in the Livingstone Mountains, I hit the trifecta: for two days I had the privilege of working alongside three amazing botanists – Brian Rance, John Barkla (ex DOC botanist and the current chair of the New Zealand Plant Conservation Network), and Geoff Rogers (ex DOC scientist with expertise in rare ecosystems).

Together, they have an astounding 100 combined years of experience working in plant conservation! Their skills and experience were two of the keys to the success of our trip.

What are ultramafic endemic plants?

We relied on Geoff’s superior knowledge of geology to learn some tips on how to distinguish ultramafic soils from fractured volcanic soils, and we also got clues from the plants themselves.

Although several species of native plants are able to grow naturally on ultramafic soils (in addition to other habitats), some species are only found on ultramafic soils (Lee 1992; see also a list here). These plants are called ultramafic endemics.

In contrast to fractured volcanic rocks, ultramafic outcrops often have few individual plants or plant species. This is mainly due to two factors. First, ultramafic soils contain extremely high levels of magnesium, which deprives plants of available calcium and other essential macro-elements. Second, ultramafics have heavy metal elements like nickel, chromium and cobalt, which are all toxic to plants.

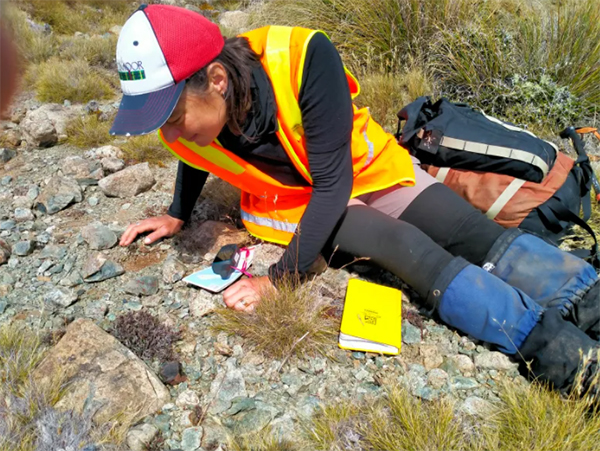

The plants that do grow on ultramafic outcrops tend to be unique specialists which have evolved to tolerate the low calcium availability and the presence of toxic heavy metals. When we found several plants known to be such ultramafic endemic species at a site, we could be reasonably certain we were standing on ultramafic soil.

Making collections of forget-me-nots in the ultramafic mountains

Some of these ultramafic endemic species – like the Chaerophyllum shown above – have not yet been formally described. The main aim of our trip was to find and collect what may be a new ultramafic species of forget-me-not (tag-named Myosotis “Mossburn”). Brian and others had seen these plants at the following Southland localities: West Dome, Black Ridge, Bald Hill, Coal Hill, and maybe the Livingstone Mountains.

We visited these sites to make new collections of this unique forget-me-not and other close relatives growing nearby (Myosotis “Livingstone” and Myosotis lyallii subsp. elderi).

We wanted to know: Can we tell them apart? Do they occupy different soils or habitats, or do they grow together at the same site? Is there good evidence that the tag-named forget-me-nots should be formally named?

Observing and collecting plants in their natural habitats is an important part of taxonomic research, and the specimens we collected on this trip are already contributing towards two new forget-me-not taxonomic papers that I am writing up.

Summary of our ultramafic field trip

- All up, we visited six different sites over as many days, putting in some massive days to locate and collect unique plants in ultramafic soils and other nearby habitats.

- For example, according to Johns Fitbit, our return day tramp to Boyd Creek tops (Fiordland National Park) comprised over 42,000 steps with an elevational gain of 1200 m!

- Over the course of the week, many exciting plants were observed, plant lists for the inspection areas were made or updated, and several plant records and images were recorded on iNaturalist.nz (see John Barkla’s and Brian Rance’s iNaturalist observations for 23-27 January 2022).

- We also made over 30 plant collections, many of which can be seen here on Collections Online. These collections are key components of my ongoing taxonomic research on native forget-me-nots, and of PhD student Weixuan Ning’s thesis research on native Azorella.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the following people and organizations for supporting this field research – Grant and Katie Catto (Black Ridge), Paul Ewing (Haycocks Farm/Hikuraki Station), John and Fay Whitehead, Chris Rance, the Department of Conservation, Te Papa, and everyone who came out with me in the field – John Barkla, Marilyn Barkla, Geoff Rogers, Mary Bruce, and especially Brian Rance. Thanks to Brian and Geoff for allowing us to use their photos.

References

Lee WG. 1992. New Zealand ultramafics. In: Roberts BA, Proctor J eds The ecology of areas with serpentinized rocks. A world view. The Netherlands, Kluwer. Pp. 375-418.

Williams PA, Wiser S, Clarkson B, Stanley MC. 2007. New Zealand’s historically rare terrestrial ecosystems set in a physical and physiognomic framework. New Zealand Journal of Ecology 31(2):119-28.