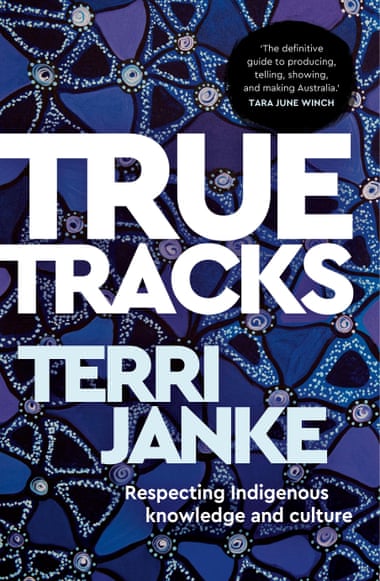

‘We need a coordinated approach’: Terri Janke’s book True Tracks is out now. Photograph: Carly Earl/The Guardian.

Steve Dow, Terri Janke: the Australian lawyer trying to stop Indigenous cultural theft, The Guardian, 20 July 2021

The Wuthathi/Meriam woman has spent 20 years finessing protocols that could empower Indigenous people to protect their arts and culture

The Cairns local newspaper dubbed her a “cultural crusader”, which shocked her: the front page story made her feel like an “impostor” and “big noter”. Flying out of Cairns, a Torres Strait woman reading the newspaper in the next seat recognised her.

“Well done, girl,” said the elder, “you can stop this theft of our cultural knowledge”.

Janke told the woman she still had so much to do. “You be strong,” the elder countered. “You’ve just got to stay on track and, if you listen with your heart, they will be true tracks. People will follow.”

The woman’s words let Janke’s “skin breathe”. She realised she wasn’t alone.

In the 1990s, Janke spent three years writing a paper on Indigenous cultural and intellectual property rights, inspired after working at the National Indigenous Arts Advocacy Association and advising a legal team in a successful copyright action brought by eight Aboriginal artists against a carpet company that had reproduced their artworks without permission.

Since then, Janke created and finessed her True Tracks framework of Australian Indigenous cultural and intellectual property principles, developing protocols for the Australia Council, Screen Australia, the City of Sydney, and LendLease.

Overseas law firms, including those from Canada and New Zealand, have sought Janke’s advice on the protocols, which cover respect, self-determination, consent and consultation, interpretation, integrity, secrecy and privacy, attribution, benefit-sharing, maintaining Indigenous cultures, recognition, and protection. She emphasises the protocols should be written into legal contracts.

Over this time, Janke has also built a case to establish a national Indigenous cultural authority, that would help protect culture and knowledge.

“It would be the first step,” Janke tells Guardian Australia. “It might not be a one-stop-shop, but there’s a lot of legwork for people working out who to speak to, and an authority could be really useful in raising awareness and capacity, giving Indigenous people the space to control their arts and their culture.”

Her new book True Tracks is a resource for respecting Indigenous knowledge and culture, which draws on 20 years of her work. In it, Janke writes of the first eight years of her life, being a “young black kid with few prospects” in Cairns who was “made to feel ashamed of my culture”. Her journalist father John and sister Toni – a lawyer and singer – encouraged her to study law, instilling in her a passion for social justice.

Janke says greater protection is needed for the “large body of oral and generationally transmitted Indigenous knowledge” excluded under Australia’s standard patent system which requires written applications. So, for example, a patent can be registered by a person who is simply told by an Indigenous person about a plant’s healing properties.

The World Intellectual Property Organization’s intergovernmental committee is considering requiring applicants to fully disclose the source of their inventions, says Janke, which could “trigger access and benefit-sharing agreements” in accordance with the Nagoya Protocol and the Convention on Biological Diversity.

Janke wants to see that protocol ratified and implemented in Australia. “We have confusion on both parts, Indigenous and non-Indigenous. It needs a lot more transparency. We need a coordinated approach between the Commonwealth and states.”

As Australian senators repeatedly fail to pass bills that would stop the sale of fake Aboriginal art, Janke is optimistic that QR codes can be used to verify authorship – with buyers using their phones to scan codes affixed to artworks. Ultimately, she says, “there is also growing consumer awareness of not wanting to buy bogus things, and consumers could drive changes in the law”.

Her book also discusses how the Australian legal system offers limited protection for Indigenous traditional design, citing the unauthorised reproduction of the Wandjina, a sacred rainmaker spirit often depicted in Kimberley rock forms by the Worrorra, Ngarinyin, and Wunambal Gaambera peoples.

The Kimberley Aboriginal Law and Cultural Centre eventually trademarked the Wandjina. “It really isn’t good enough protection, but it is one way of saying, if you use it commercially, [the custodian groups] own it.”

Meanwhile, the exclusive licensing arrangements held by non-Indigenous people of the Aboriginal flag designed by Luritja artist Harold Thomas has caused “growing distress” in Indigenous communities, Janke says. In 2020, a Senate inquiry rejected calls for the federal government to invoke its constitutional power to compulsorily acquire the copyright in the artwork as well as licenses to reproduce the flag design, which would free up its wider use.

Janke believes compulsory acquisition is the best way to resolve the issue. “Then you’ve got a question of ownership, so you need it to be guarded by the right people and attribution to the artist who designed it. It’s got a history that needs to be told, and consistently linked to, and the moral rights need to be adhered to.”

Janke’s firm also helped develop the governance framework for the online platform of the Keeping Place Project, a repatriation effort shared by traditional owner groups and resource companies in the Pilbara. Given Rio Tinto blew up sacred Juukan Gorge in May 2020, perhaps the project has not been enough to ensure mining company respect?

“There needs to be total changes in the heritage laws, around planning and much more forward-thinking and engaging with people,” Janke says.

“Yes, Juukan Gorge happened, and it was totally devastating, but there’s been many like that, and there’s been some since.

“You’ve got to think about how Australia values its cultural heritage. Australians will travel the world to see places in Mexico or Machu Picchu [in Peru] or Cambodia or Rome, but Australia has cultural landscapes and sites even older.

“We are living in a country that has amazing world cultural heritage, and we need to be really respectful of it.”

True Tracks: Respecting Indigenous Knowledge and Culture by Terri Janke is out now through UNSW Press/NewSouth