The Victorians at Christmas, Ashmolean Museum Oxford, December 2023

To mark our major exhibition Colour Revolution: Victorian Art, Fashion & Design showing now over the festive season, we explore how the Victorians popularised and celebrated Christmas in this selection of artworks and Victorian Christmas cards.

QUEEN VICTORIA’S CHRISTMAS TREE

At the dawn of the 19th century, Christmas was hardly celebrated. By the end of the century, Christmas had become the biggest annual celebration in the British calendar.

As well as having an impact on society as a whole, Victorian advancements in technology, industry and infrastructure made Christmas an occasion that many more British people could enjoy. As our current Colour Revolution exhibition shows so vividly, Victorian life was full of colour and not the smog-filled dark and dreary time we often imagine.

Two of the most popular seasonal traditions also emerged in the Victorian era, the Christmas tree and the Christmas card.

The Germans are credited with first bringing evergreens into their homes and decorating them, a tradition which made its way to the United States in the 1830s. But it wasn’t until the German-born Prince Albert introduced the tree to his new wife, England’s Queen Victoria, that the tradition took off.

The couple were sketched in front of a Christmas tree in 1848, and when the Illustrated London News published the drawing, royal fever did its work.

The popularity of decorated Christmas trees grew quickly, and with it came a market for tree ornaments in bright colours and reflective materials that would shimmer and glitter in the candlelight.

Mechanisation and the improved printing processes meant decorations could be mass-produced and advertised to eager buyers. The first advertisements for tree ornaments appeared in 1853.

Victorians would often combine their sparkly bought decorations with candles and homemade edible treats, tied to the branches with ribbon.

The Christmas tree was originally a festive tradition stemming from the Roman Saturnalia. These festivities, which marked the winter solstice in December, celebrated Saturn, the Roman god of time and agriculture. During the winter, branches served as a reminder of spring – and became the root of our Christmas tree.

The Victorians also continued another Saturnalia tradition of kissing under the mistletoe at Christmas. This had become popular in the 1700s, as it was thought to symbolise fertility and romance. According to Victorian custom, it was said that a maiden who refused the offer of a kiss under the mistletoe would jinx her chances of getting married the following year.

SIR HENRY COLE’S CHRISTMAS CARD, THE FIRST

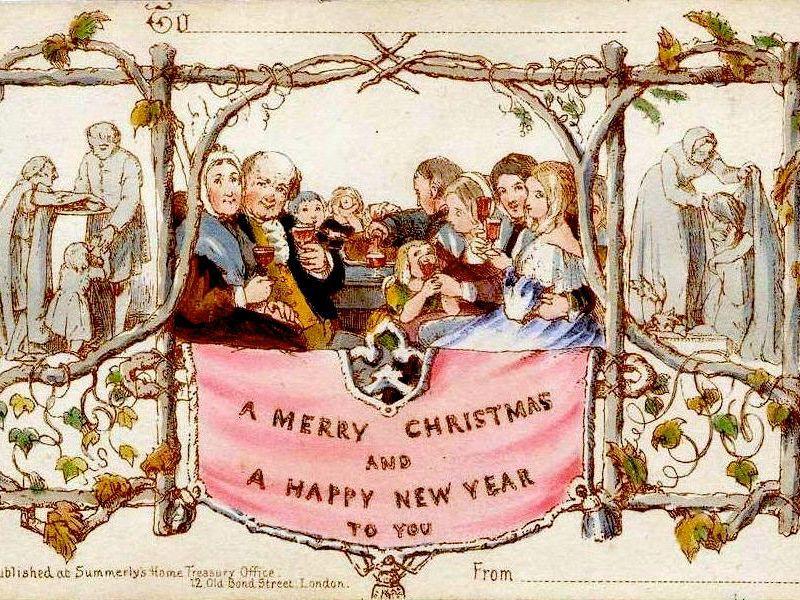

It was Sir Henry Cole, the first director of the South Kensington Museum (later the V&A), who introduced the idea of the Christmas card in 1843.

Finding he was too busy to send his customary Christmas letters to all his friends and acquaintances, Cole commissioned the artist John Callcott Horsley to design a festive-themed card for him to send instead. He had 1,000 printed, and those he didn’t use himself were sold to the public.

The card design, in true Victorian style, depicted the two sides of Christmas. A central image which portrayed Henry’s family happiness with a plenitude of food and drink was flanked by two scenes showing the less fortunate poor and needy being helped with gifts of food and clothing.

The card was of a similar size to a postcard and carried the message ‘A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to You’.

Later in the century, improvements to the chromolithographic printing process made buying and sending Christmas cards affordable for everyone.