Tony Perrottet, The sinister history behind some of the world’s first tourist sites, BBC Travel, 6 February 2024

A recent TikTok sensation in Paris had a decidedly ghoulish air: a string of viral videos showed adventurers sneaking into the medieval catacombs underneath the city, where the pitch-dark tunnels are packed floor-to-roof with the bones of some six million dead people.

In this morbid craze, people break in through illegal entrances, walk across floors carpeted with human bones, crawl through crevices packed with femurs and explore the city’s roughly 300km of off-limits routes with headlamps – occasionally getting lost. While some TikTok commentators in Paris have warned of the risks and potential dangers, the trend taps into a much deeper appetite that travellers have long had to rub shoulders with the dead.

More than one million tourists line up every year at the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in Cairo, Egypt, filing dutifully into a sepulchral below-ground chamber where the embalmed corpses of Ramses II (the Pharoah of the Bible) and Queen Nefertiti lie exposed in their coffins. Thousands more traipse into the mausoleums of Chairman Mao Zedong in Beijing, Ho Chi Minh in Hanoi and Vladmir Lenin in Moscow to see their embalmed bodies. Meanwhile, the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia, one of the last surviving 19th-Century medical museums, lures 135,000 visitors a year to gape at such grisly curiosities as pieces of Albert Einstein’s brain, the tumour removed from President Grover Cleveland’s jaw, conjoined stillborn twins and rows of Victorian-era skulls.

“Western society has a fascination with the macabre,” said Dr Michael Pickering, associate professor in the Department of Heritage and Museum Studies at the Australian National University in Canberra, who has studied issues surrounding the display of human remains for more than three decades. “We have become very insulated from death in the First World, so people are excited by being shocked. It’s an adrenaline rush.”

At the same time, the whole premise of exhibiting body parts has been criticised in recent years as unethical. One high-profile mea culpa occurred in October 2023, when the new director of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York, Sean M Decatur, announced that the last human remains would be withdrawn from public display. Many belonged, the museum admitted, to”victims of violent tragedies or representatives of groups who were abused and exploited, and the act of public exhibition extends that exploitation”. Acquired without consent, remains were treated as objects, robbing them of their dignity.

The process is now complete: no longer can travellers wander across the street from Central Park and see the skeleton of a 1,000-year-old Mongolian warrior laid out in a reconstructed burial site, or a 19th-Century Tibetan apron made from human bones.

Critics complain that hiding such exhibits robs the public of valuable educational insights. But other institutions, including the Mütter, are feeling the pressure. Still, the question lingers: can we learn from human remains, or are we merely indulging a morbid curiosity, with museums profiting from the work of tomb-raiders and body-traffickers?

The world’s first tourist sitesHuman remains have long fascinated travellers. In the Middle Ages, Christian pilgrims would journey for months across Europe to gaze upon John the Baptist’s severed head (which can still be seen at Rome’s Basilica of San Silvestro in Capite); the tongue of St Mary of Egypt (on display in the Church of St Blaise in Vodnjan, Croatia); and the “holy foreskin”, the only piece of Jesus’ flesh that remained after his ascension into heaven. (Saved after the Saviour’s circumcision, this choice relic was claimed by half a dozen churches across Europe). These ancient relics helped create some of the world’s first tourist sites. Body parts were also big business. The Catholic Church built lavish reliquaries and created an incipient hospitality industry around them, and wealthy pilgrims would fork over large sums to see these remains up close.

In the modern era, the emphasis shifted from displaying the remains of saints to celebrities. Inspired by the Romantic movement, travellers in the early 1800s sought out “secular relics”. The body parts of creative geniuses (the poet Shelley’s heart and Beethoven’s ear bones, for instance) seemed to offer a visceral connection to their owners’ near-divine talents. Today, Galileo’s middle finger can be seen in Italy, at the History of Science Museum in Florence, in an ornate, egg-shaped glass ball.

My favourite celebrity relic is Napoleon’s penis, which was allegedly removed from his body by a vengeful Italian doctor at the autopsy in 1821. The emperor’s member was purchased in 1977 by America’s top urologist, John Kingsley Lattimer, who kept it under his bed in Englewood, New Jersey, for decades. The family only showed it to serious researchers – including, a decade or so ago, myself.

Another, far more gruesome shift occurred in the 19th Century, as science became the rationale for museums in Europe and the United States to collect and display the dead – particularly Indigenous people from far-flung corners of the globe. In the Victorian era, national institutions spent fortunes funding archaeological expeditions to pillage historical burial sites in the deserts of China, the icy wastes of Alaska and the mountains of Peru.

Even more sinister were anthropology departments, which sent teams to “harvest” the skeletons of deceased Indigenous people from Texas to Tasmania, pillage bones from grave sites or after massacres, or purchase them from roaming professional “bone collectors”.

The original purpose of this was to promote a bizarre “pseudoscience” called phrenology, a discredited belief that the study of bones – especially skulls – could reveal inherent racial traits from intelligence to industriousness. After the publication of The Origin of the Species in 1859, misguided followers of Charles Darwin used phrenology to “prove” that Indigenous people were lower on the evolutionary scale than Anglo-Saxons, and thus justify their imperial conquest. Museum curators across the Western world wanted the full collection of “racial types” to display, and Indigenous skeletons were traded around the globe like baseball cards. Every curator, it seemed, wanted a skull of a Sioux from Dakota, a Herero from Namibia and a Hokkaido islander from Japan.

Why is displaying human remains controversial?Not everyone in the West regarded displaying the dead as morally justified. Even some Victorians were uneasy at the parade of gawkers flocking to see Egyptian mummies, and Egyptologists were regarded by some as one step above grave-robbers.

But it’s only recently within the museum world that there’s been a broad shift in dialogue surrounding the ethics of exhuming, studying and displaying human remains. This rethinking has been led by Indigenous groups, who have demanded that their ancestors’ remains be removed from museum display and returned to their descendants.

In the United States, Native American activists have been pushing for such moves from museums for decades. “What gives scientists, archaeologists and anthropologists the right to go into burial grounds and take what they want?” asked Hillary Kempenich, an artist, museology scholar and member of the Turtle Mountain Anishinaabe in North Dakota. As a 10-year-old student, Kempenich learned that the remains of members of her tribe were still being kept in boxes in the University of North Dakota in North Fork.

“I was horrified,” she said, noting that such display is a spiritual violation for Native Americans. “People may no longer be here to use their bodies, but we should still be respectful of them.”

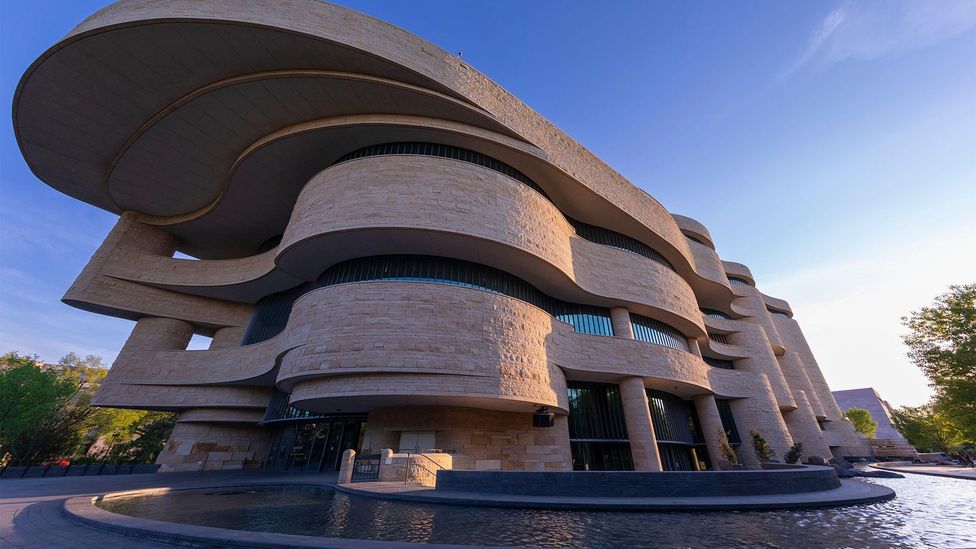

Many museums have been removing their Indigenous body part exhibits, including the Smithsonian Museums in Washington DC, the Hume-Carnegie Museum in Chicago, the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, the Manchester Museum and the South Australian Museum in Adelaide.

“It’s an attempt to reconcile with our colonial past,” said Pickering, who worked as a curator at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra for more than two decades. “If our remains are important, then others are, too. There are no first- and second-class human remains.”

Still, this doesn’t solve the more fundamental problem, Pickering explained: every major anthropology institution in the Western world, from The British Museum in London to the Museum of Mankind in Paris to the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington DC, has storage rooms stacked with the bones of Indigenous people, which were being “harvested” well into the 20th Century. The AMNH, for instance, still possesses the remains of some 12,000 individuals, and while it has returned some 1,000 sets of Native American remains to their descendants since 1990 under the federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), it still houses 2,200 Native American skeletons.

In 2023, nonprofit newsroom ProPublica estimated that more than 110,000 remains of Native American, Hawaiian and Alaskan people are still in US museums, universities and federal agencies. The total number of Indigenous people from all over the world in US museums may be closer to half a million. Multiply that for international museums and the figures become staggering.

In the US, the repatriation of Native Americans’ remains under NAGPRA has been a painfully slow process: those stored in the University of North Dakota, for example, only began being returned in 2022, more than 30 years after the legislation was passed.The process has often been hindered by institutional lethargy, poor museum recordsand (according to many curators) the difficulty of finding descendants of some Native peoples who were tragically decimated, since the law also requires that a “cultural affiliation” with the past be proven.

This, according to Kempenich, is a loophole to avoid compliance.”Ultimately the museums need to go out and consult with members of the communities and the families involved. They have to do this with tact,” she said. But for Kempenich, returning human remains is only one part of the story. She and other activists argue that there should also be reparations for the living to help Native Americans deal with the legacy of abuse that led to the looting of their grave sites in the first place. “In my community, 12 to 15% of the population is Native American. What is being done for them to repair the generations of wrongdoing?”

To complicate matters, NAGPRA deals only with Native American remains. There is no equivalent law requiring US museums to return the remains of Indigenous people from other countries, leaving each to decide what to do with its collections from Africa, Oceania, Asia and Latin America. As a result, US museums (which tend to be under-staffed and under-funded) have often dragged their heels until forced to act. In 2022, four years after the Australian government applied diplomatic pressure to convince the Smithsonian Institution to return the last remains of people from the Aboriginal Gunbalanya community obtained without consent in 1948, their bodies were finally returned home.

Education versus entertainment

Recently, this ethical rethinking of exhibiting Indigenous human remains has spilled over into the display of all human relics. In 2022, the Mütter Museum become a case study when its newly appointed executive director Kate Quinn declared that many of its anatomical exhibits were unethical, whether they were from Indigenous people or not. While some individuals in Europe and the US had willingly donated their bodies to the museum for medical study, Quinn said, others definitely had not, including some of the museum’s most popular exhibits.

For example, the corpse of the “Soap Lady”, Mrs Ellenbogen, whose fatty tissue had decomposed so that she seemed naturally mummified, had been illegally dug up in a cemetery in 1873. Quinn pointed out that Joseph Leidy, a curator at Philadelphia’s Academy of Natural Sciences, had lied to the gravedigger and said Ellenbogen was his grandmother. Likewise, the Mütter’s core collection of skulls was purchased from an Austrian phrenologist named Josef Hyrtl in 1873, who took them mostly from poor Eastern Europeans without consent. While the Mütter Museum’s exhibits remain popular today, explanatory notes now provide historical context: “Although collecting skulls was legal in Hyrtl’s time, the practice was discriminatory, non-consensual, and degrading.”

Such changes provoked outrage in conservative circles: “Cancel Culture Comes for Philly‘s Weirdest Museum” read the title of a June 2023 op-ed in the Wall Street Journal, which accused the Mütter of pandering to the “woke elite”. Thirteen staff members resigned in the first nine months of Quinn’s tenure over what one called “the deconstruction of the museum”, and a petition to halt the changes garnered 21,000 signatures from the public in less than two weeks.

Others argued that the Mütter’s anatomical exhibits still have medical value: Researchers have examined them for rare historical DNA samples and damaged tissue, and studied the remains of cholera victims. Even the Hyrtl skulls were examined by war crime investigators in the 1990s working in mass graves after the Balkan conflicts. Critics respond, however, that this research role could be served without putting them on display. “Why are the weirdest deformities and curiosities still being exhibited?” Pickering asked.”Why are the craniums laid out like Aztec skull racks?”

The answer, Pickering suggests, is that it’s entertainment: “Many world museums are struggling financially. They need to attract an audience. As a result, they degenerate into entertainment palaces. Their purpose is no longer for education.”

The ethical debate is certain to continue in the museum world, as curators around the globe deal with their human collections in haphazard fashion. But even the most sincere change of heart is unlikely to close such profitable exhibits as the Egyptian mummies, or distract the flow of TikTokers from illegally entering the catacombs of Paris.

Humans – living ones, that is – seem to be hard-wired for hanging with the dead.

Tony Perrottet is the author of six books, including Napoleon’s Privates: 2,500 Years of History Unzipped.