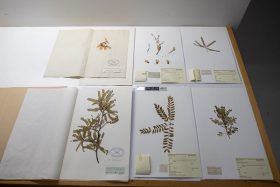

Carlos Lehnebach with some of the acquired 1870s specimens in their original bundle, 2020. Photo by Rachael Hockridge. Te Papa.

Rachael Hockridge, Captain Cook’s 150-year-old kōwhai specimens uncover Rapa Nui (Easter Island) secrets, Te Papa, 19 Feb 2020

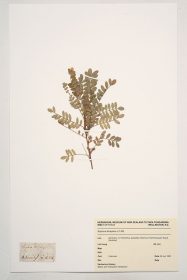

A single specimen of toromiro – a close relative of our own kōwhai and extinct in the wild – has been discovered in our botany collection, where it’s been kept safe for 150 years.

Thanks to new DNA analysis, Genetic Scientist Lara Shepherd and Botanist Carlos Lehnebach think the specimen grew from seeds collected on Captain Cook’s visit to Rapa Nui (Easter Island).

They talk us through their research and explain how this discovery could help reintroduce the species to their home.

What is toromiro?

Toromiro (Sophora toromiro) is a yellow-flowering tree that was found only on Rapa Nui (Easter Island). It’s in the same genus as kōwhai (Sophora).

Toromiro is so similar to kōwhai we’d forgive you if you couldn’t tell them apart. And it wasn’t until 1921 that toromiro was recognised as its own species.

Sadly, toromiro has been extinct in the wild since the 1960s. However, it currently survives in a number of botanic and private gardens. These plants are thought to have descended from seeds collected in the 1920s–1950s, including from the last known wild tree.

But new Te Papa research has changed everything we knew about its early cultivation.

Our toromiro specimen

In the 1870s Director of the Colonial Museum Sir James Hector acquired 28,000 dried plant specimens from the British Museum.

Housed in our botany collection, these specimens largely remained in their original boxes and bundles for the next 150 years. But recently, volunteers helped us undertake the first examination of a selection of these specimens.

To Carlos’ surprise the collection included six specimens of kōwhai taken from cultivated plants in continental European gardens, including the former Royal Gardens at Herrenhausen, the University of Gottingen in Germany, and the nursery of Jacques Philippe Martin Cels in France. These specimens date between 1765 and 1864.

DNA analysis

Because the specimens had been untouched for 150 years, they were in amazing condition.

“The leaves were still really green, and the flowers yellow – they looked so fresh! Because of this, their DNA would have been preserved,” says Carlos.

“I asked Lara if she’d take a look, as she’d previously undertaken work studying kōwhai DNA.

“The names on the labels indicated they were from New Zealand, so I was interested to know from which regions, particularly because the dates on the specimens suggested they were collected during one of Cook’s voyages.

“It didn’t occur to me that they were specimens from a Sophora species from outside New Zealand.”

When the results of the DNA tests came in, Lara was sitting in a motel room in Dunedin.

“I emailed Carlos and said, ‘you’ll never guess what we’ve found – one of the plants is a toromiro!’” she says. “He didn’t believe me.”

Lara and Carlos then double-checked the morphology of the plant by looking at features of the leaves such as the shape and the hairs. Their analysis and research backed-up the results of the DNA test.

The plant had been misidentified, and it was an Easter Island toromiro.

Collected on Cook’s voyage?

The handwritten date on the toromiro specimen says ‘1800’. As it had been sent to James Hector in 1870, there’s no reason to suggest this is incorrect.

The first botanists to visit Easter Island were Johann and George Forster with Anders Sparrman on Cook’s second voyage (1772–1775).

Although there is no record of them collecting toromiro seed, they did collect herbarium specimens of this species.

Sparrman collected seeds of various plants to send back to Europe, so it’s likely toromiro seeds were also collected.

So, if they were collected between 1772–1775, this would provide enough time for the seeds to grow into large enough plants for a branch to be removed and pressed to make a herbarium specimen by 1800 – and then sent to Hector in 1870. Thus concluding that this plant is likely a descendant of a Cook specimen.

“Natural history collections really are a window to the past,” Carlos says. “This has been sitting in a box for 150 years, but new technology means we can find out provenance and understand how people have moved plants across oceans.”

Although there is no record of them collecting toromiro seed, they did collect herbarium specimens of this species.

Sparrman collected seeds of various plants to send back to Europe, so it’s likely toromiro seeds were also collected.

So, if they were collected between 1772–1775, this would provide enough time for the seeds to grow into large enough plants for a branch to be removed and pressed to make a herbarium specimen by 1800 – and then sent to Hector in 1870. Thus concluding that this plant is likely a descendant of a Cook specimen.

“Natural history collections really are a window to the past,” Carlos says. “This has been sitting in a box for 150 years, but new technology means we can find out provenance and understand how people have moved plants across oceans.”

Why this discovery is so important

The National Forest Corporation in Chile is trying to reintroduce toromiro to Rapa Nui. For this to succeed, it’s best to have genetically-diverse plants.

“This means the species is more likely to adapt to changing environments and resist diseases,” Lara says.

All known living species of toromiro are thought to descend from the last wild tree in the 1960s – this means there isn’t much genetic diversity.

But now, there’s a small chance there are some living descendants from our plant, which is 150 years older, still in cultivation.

Calling European botanical gardens

“We’d love all large-leaved Sophora growing in European botanic gardens to be examined and those that are morphologically consistent with toromiro included in future genetic analyses.” Lara says.

It’s very possible that toromiro plants descended from Cook’s early collections of seeds are still in cultivation in Europe today and this genetic diversity could be really important for the conservation of the species.

And hopefully one day Sophora toromiro will once again thrive on Rapa Nui.

Read the full research paper