Arthur Loureiro, Study for ‘The spirit of the new Moon’ 1888, oil on canvas. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane Purchased 1995. Queensland Art Gallery Foundation Grant with the assistance of Philip Bacon through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation. Celebrating the Queensland Art Gallery’s Photograph: QAGOMA, CC BY-SA.

Mitch Goodwin, Friday essay: romancing the moon – space dreaming after Apollo, The Conversation, 5 July 2019

Last weekend I sat down for a chat with Lisa Sullivan, senior curator at the Geelong Gallery, to get a handle on the gallery’s new exhibition, The Moon. Two and a half years in the making, the exhibit is timed to coincide with this month’s 50th anniversary of the Apollo program’s crowning achievement: a manned spaceflight to the lunar surface.

The exhibition is an ambitious take on this event and, more broadly, our relationship with our nearest celestial neighbour. Or as Sullivan characterises it: “a beautiful poetic presence in the night sky”.

The moon is of the Earth, the product of a celestial collision, whether in part or in whole. We consider it as we would a fellow traveller. After all, the near side of the moon is perhaps the grandest example of pareidolia – the psychological phenomenon that makes us see patterns (often human characteristics) in random objects. And so it is that we see our likeness emblazoned on its crater-filled surface.

We are enamoured by the courting arc of this shapeshifter across our night sky. We anthropomorphise its gaze – the “man in the moon” is said to be “facing us”, while the concealed facade is known as “the dark side”. The moon has revealed itself to be a complicated character.

Georges Méliès, A trip to the Moon (Le voyage dans la lune) (still, detail) 1902, black and white; silent, duration 00:10:19.Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Melbourne.

The Geelong Moon exhibition is an opportunity to examine this relationship, to pause and reflect on how our perception and interpretation of the moon has evolved. This is particularly relevant now, not only with the Apollo anniversary but also in the absence of a return to the moon and our retreat from manned space exploration. We do so now at a distance, via Twitter and YouTube. Our experience of the moon and space has become a virtual one.

In the exhibition, one is reminded not of the record of history so much – though it’s there in those iconic photos, the media sampling and the multitude of graphical renderings – but more so how an object so ubiquitous as the moon becomes a conduit for a shared narrative.

There are no werewolves in Geelong, but there is a blend of fantasy, the domestic and the ancient. There is Arthur Loureiro’s painting Study for The spirit of the New Moon (1888), inspired by an epic poem in which the goddess Venus wards off the dangerous seas allowing safe passage for the explorer Vasco de Garma.

And there is a James Gleeson painting, The Siamese Moon (1951), demonstrating in exquisite detail the moon’s ethereal embrace, and according to Sullivan, how “important the moon was to the surrealists in terms of dreams and the subconscious and representing the unknown”.

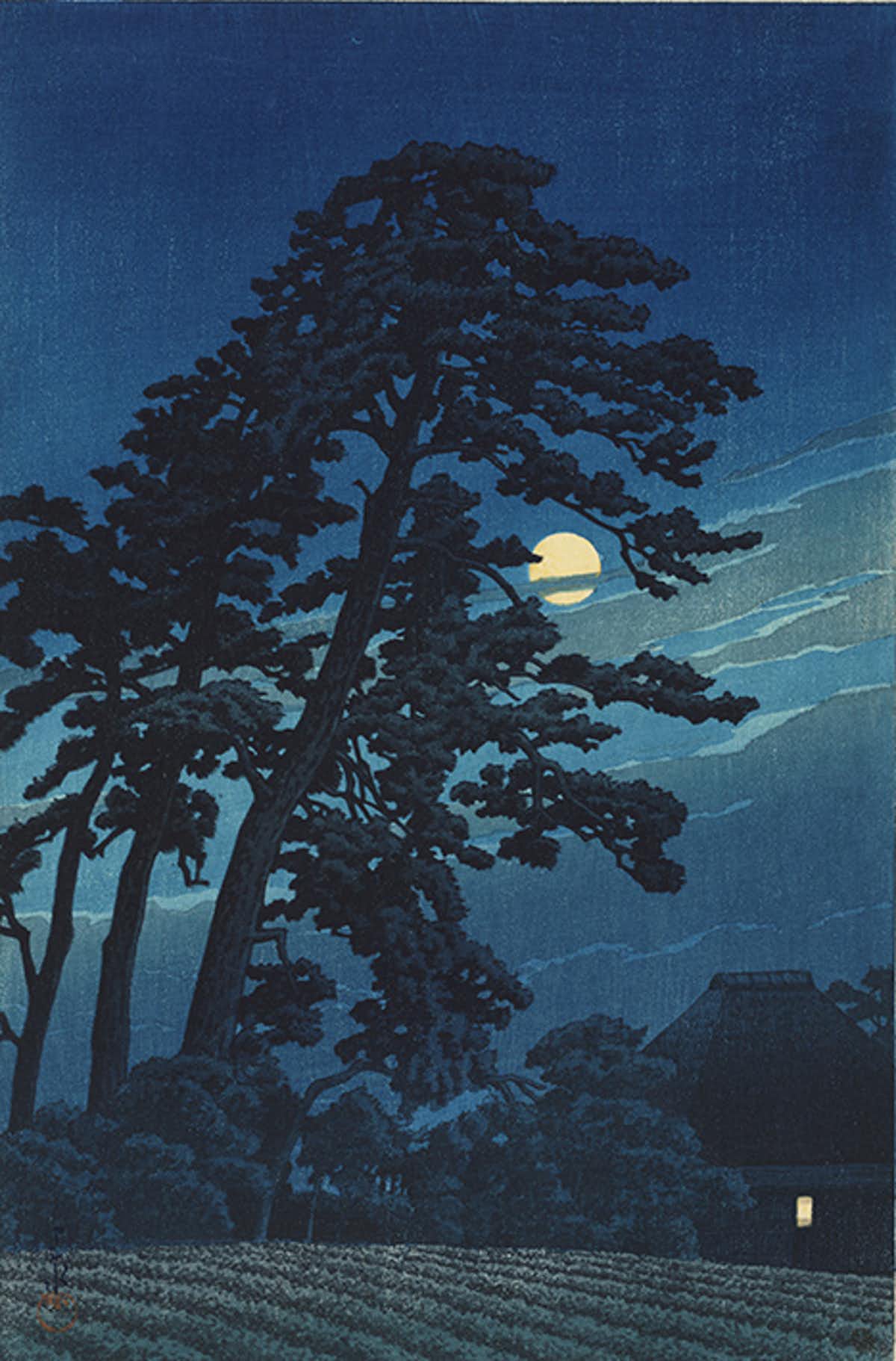

Images of the moon, like Kawase Hasui’s Full Moon in Magome (1930), evoke familiarity with the moon as a companion, a beacon or as a singular yet powerful light source; a seductive aesthetic if there ever was one.

The moon across time and culture

It is impossible to imagine today, but there was a time when only moonlight lit the streets and the pathways, its luminance stretching out across the moors and the ocean swells. It wasn’t until as recently as around 1807 that 23 of the first gas-fired street lamps were installed in London. By 1825, there were 40,000.

When electricity finally did arrive in the 1870s, the economical route to municipal lighting was by erecting light towers, designed to mimic the moon, the first appearing in San José, California, in December 1881.

There are ancient stories to tell here too. Oral traditions of Indigenous Australians not only mapped the night sky, but the stars helped to choreograph one of the earliest cultural dreamings of space. First Nations people had a sophisticated understanding of the subtle variations in the night sky.

The moon too is a strong romantic presence in Indigenous culture. Hector Jandanay’s moon dreaming Garnkeny (Moon man) (1993), on display in the Geelong exhibition, tells a story of forbidden love, the merging of Earth and Moon and the endurance of love eternal, reborn in the lunar cycle.

Through Sullivan’s curation of the exhibition, cultures speak across time, the works becoming a collective voice that detail the technique of space exploration but also the mystery of what it goes in search of. “People do ask me, ‘Is it about the science?’ and I say, ‘No, it is about the romance.’”

Photographs behind glass appear like rare artefacts from a distant time. Familiar iconic photo plates – the Earthrise image from Apollo 8, a moon boot in the space dust, the Apollo 11 Landing Module hurtling towards the lunar horizon – sit alongside the rare and the uncommon, such as photographic prints of the Russian Luna 3 flyby of the far side of the moon in 1959 and the landing of Lunar 9 spacecraft in 1966.

There is a stunning engineering document, The Apollo 11 Earth Orbit Chart (1969), showing in detail the rocket revolutions, ground tracking trajectories and burn initiation points of the launch vehicle as prepared by the US Department of Defence.

And then there is the lunar map Almagestum Novum (published in 1651) by 17th-century astronomer Giovanni Battista Riccioli, which has been playfully decoded and re-purposed by Mikala Dwyer in her installation piece, The Moon (2008).