Essay: The pie chart of happiness by Patrick McIntyre, Sydney Theatre Company, 19 April 2017

UPDATE: NOW AVAILABLE AS A VIDEO

This essay, originally published in 2017, was updated and reframed by Patrick McIntyre as a presentation for the Innovator Series at the 2018 Australia and New Zealand Tessitura Regional Users Conference. Watch it here, or read the original essay below.

Sydney Theatre Company’s Executive Director Patrick McIntyre was recently invited to write an essay for The Sydney Culture Essays, published by the Committee for Sydney, which aims to capture the thinking of some of our city’s leading cultural voices. Other essayists include Sydney Festival Artistic Director Wesley Enoch, MCA Director Elizabeth Ann MacGregor, and artist Abdul Abdullah.

Patrick’s essay ‘The Pie Chart of Happiness’ examines how we articulate the value of culture and proposes a new model with which to do so.

I like to keep it simple.

A specialised message for a particular audience can be as windy and exclusive as it likes. Contextualised jargon can be OK, even amusing.

But a message that is intended to be universal needs to be rugged, plain and humble. It needs to be simple.

This is something that any advocate for the value of arts and culture knows well, yet still struggles with.

When making a case for culture’s value, there is so much to say, and so many people to convince. Audiences, customers, funders, patrons, governments, the media. We are torn between using our own, sometimes esoteric jargon on the one hand, and that of the economic impact study on the other. We pull our message out of shape in trying to show that we are both really, really broadly accessible, and provide good return on investment to boot.

We’re clearly not doing it right. Despite Australia Council research finding that 85% of Australians think the arts make for a richer and more meaningful life, when it comes to articulating its value, culture still has a perception problem. We are a highly culturally engaged nation, yet we do not self-identify as ‘cultural’. It’s not part of our national myth-making. The value of culture, which we enjoy, goes below the radar, and this can adversely affect policy and resourcing decisions.

In an age fixated on metrics and evidence, is it perverse to argue that the main value of culture is happiness?

Are we afraid of looking too simple?

†

Between 2010 and 2013 I was involved in a series of meetings convened by US arts peak body National Arts Strategies (NAS). The gatherings were between arts and cultural leaders from around the world, and leading business academics. They took place at the Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan, the University of Texas at Austin and Harvard Business School, with a collective debrief held at the conclusion of the series in Sundance.

There were around 80 arts and cultural workers from around the world involved, with a broad definition of culture taken with representatives from organisations including large orchestras, community choirs, marine parks, museums and service providers.

NAS wanted to build the capacity of cultural leaders to increase the resilience of the sector in uncertain times characterised by scarce resources, rapid technological change and the increasing need for the ‘non-profits’ of old to compete for attention and finances in a crowded, complex market.

Amongst debates on topics ranging from media convergence to community diversity and the future of money, the slippery notion of ‘relevance’ always rose to the surface. The vital importance of art and culture was something fervently believed in by us all; yet the simple articulation of ‘why?’ remained frustratingly beyond us.

The key term here is ‘simple’. As arts professionals, we were all versed in the differences between intrinsic and extrinsic value. Perhaps because it’s easier, and perhaps because we’ve been trained into it over a generation of economics-heavy public discourse, we were all able to reel off compelling statistics about the educational and well-being programs provided by our organisations, to quote our attendance numbers or cite figures from economic impact studies about cultural tourism and the night-time economy. We were aware of the various 250-page reports commissioned by governments and foundations that comprehensively champion both intrinsic and extrinsic benefits—yet their very density means they tend not to easily lend themselves to use in broad-base advocacy. We were quite good at arguing amongst ourselves the relative merits of zoos, symphonies and community organisations. But when pushed to address the question, ‘Culture is important because?’, a concise, relatable and true response was hard to land on.

Furthermore, the more we tried to agree on key terms or concepts of cultural value, the more our distinct terminologies, or the peculiarities of the cultural forms we worked in, drew us apart, not together.

Yet, listening to the lively discussions of this passionate, talented and experienced cohort over a period of years, I became convinced that we were all saying the same thing after all.

First, our shared conviction was that cultural value is a societal bedrock. We are culture. We are made of it. Whether or not we are aware of it, we view the world through cultural filters shaped over centuries by language, history, philosophy, travel, religion and art. Culture itself informs the way we see, talk and think. It is hard to measure the value of culture because it is almost impossible to point at it and define it, to describe it as an external phenomenon. To perceive something that is coded into our very means of perception creates a feedback loop from which it is difficult to extricate ourselves.

If we are made of culture, it makes sense that being aware of this is important. The ability to unpick and understand the ways in which we relate to the world around us will help us to create stronger relationships, to understand difference, and to make better decisions. Concepts like self-knowledge are so pervasive and fundamental that they are surely immeasurable—they are, in fact, the foundations on which measurable strategies are based.

If this sounds evasive, it leads to another challenge in answering the question of culture’s fundamental importance. What if the answer is, because it just is? People love culture, they find it satisfying, inspiring and it makes them happy. Isn’t that enough? Surely, the more happiness in the world, the better? I don’t think anyone would disagree with this belief, but how do you prove it? How do you even set about gathering the evidence that happiness is good, in and of itself? The more you talk about happiness, the more the word itself seems hopelessly naïve. Sure, there has been plenty of interesting work looking at some extrinsic benefits of happiness. Research tells us, for example, that lonely old people have better health outcomes once they get a cat, which brings happiness (except perhaps to dog people). But you don’t have to need happiness for a particular functional reason for it to be good for you. Happiness is good in every moment of your life, but no one’s about to study every moment of everyone’s life.

There was a strong sense amongst the NAS group that the more individual happiness there is, the greater the communal happiness—a contributor to social harmony, productivity and what used to be called ‘world peace’. All institutions of all scales were able to discuss how their programs and services contributed toward individual and communal wellbeing. They provided personal stimulation via participation or consumption. They were aware of the enhanced value of shared interests and experiences, and accordingly optimised their facilities to enhance interactions with others, and they provided the opportunity for further enrichment and learning, whether through formal educational programs for schools or adults, or simply through the possibility of a deeper engagement with culture, its practitioners, traditions, histories and techniques. These three pillars—stimulation, connection and learning—seemed to hold whatever the scale of the organisation, or whichever type of cultural activity it hosted.

While in public discourse, “cultural policy” is often taken to mean “arts policy”, we should recognise, note and celebrate that art is but one branch of culture, as NAS did in selecting the members of its program. Others branches include philosophical and political traditions, history, language, sport and games, superstition, folklore, a love of ‘the great outdoors’, ceremony and ritual, fashion and food.

Struck by the clarity of the three pillars, I began applying them to other forms of cultural activity or institution, say a cricket club, a university, a national park, and found they could be equally applied.

In culture, the concept of ‘externalities’ applies: that is, benefits can be conferred on people by an activity with which they are not directly involved. Do I visit the Sydney Cricket Ground? Never. Am I glad it exists? Yes, because cricket is an important part of our culture. Cricket can be enjoyed as a game to be played with friends and family, or watched with a crowd. With practice, one can become better at it, progressing from backyard to elite level. It has a whole heritage of rules, scores and heroes that can be sifted through and obsessed over. Winning and losing exercises the emotions. A great game can buoy you through the week, and generate good will amongst strangers. The display of technical mastery can create awe and inspiration that can heighten our expectations of ourselves in our own endeavours. I’m not remotely interested in cricket, but I can recognise the benefits to my community of the stimulation, connection and learning it offers, and I’m glad of it.

I can go for years without thinking about the 50m butterfly, but if Australia wins bronze at some far-flung Olympics, I love sharing a knowing smile with a random passer-by. Swimming, like cricket—and, tellingly, unlike culture—forms part of our collective Australian mythology. We tend not to think of these moments as other than fleeting: abundant, common, dispensable, value-less. But we’d miss them if they stopped.

A cohesive, productive society is made up of endless accumulations of such moments. All forms of culture and recreation play their part—even those that don’t bring us personal joy, because we benefit too from the joy of others, however inscrutable.

So, happiness is important for personal wellbeing and, by extension, communal wellbeing. A community is an aggregation of individuals—it follows that an aggregation of happy individuals will result in a happy whole. This is simplistic: not everyone is happy all the time, and not all people are made happy by the same things. Our own experiences and interests make us intrinsically different from others: therefore a community is also an aggregation of idiosyncratic differences that together give distinctive identity to a group. Culture makes us different, but can also bring us together, and give us the insights that help us to interact productively and generously. It can bring different people together around a shared interest. Art, history and language can help us to understand people of different cultural traditions—it even helps us get to know people from the past. National narratives serve to create fellow-feeling.

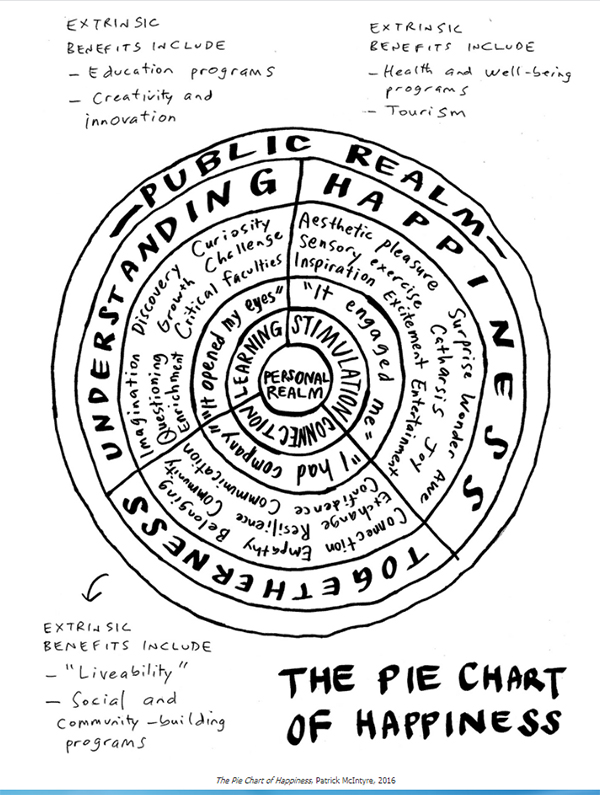

This mini-revelation—three pillars of value, scaling from the personal to the public realms—gave rise to the model above, which I call the Pie Chart of Happiness.

Initially a doodle in a margin, I wonder whether it might be a useful template to demonstrate how the intrinsic values of culture in the private realm amplify into the public realm as communal value. It traces programmatic, or extrinsic, benefits back to the intrinsic, providing opportunities to leverage these, including for economic gain, without losing sight of the fundamentals. Hopefully, some alignment can be brought to the vexed challenge of advocacy by finding a home for everything—from entertainment to self-knowledge to rarefied, esoteric mastery—in the one basic architecture of value that is unashamedly simple.

Here’s Brian Eno, from his 2015 John Peel Lecture:

“Art is everything that you don’t have to do… You have to eat, for example, but you don’t have to invent Baked Alaska. We have to move, but we don’t have to do the rumba.”

So why do we do the rumba?

Simply, it makes us happy.

See also: Introducing our new CEO Patrick McIntyre