The Powerhouse Museum chief executive Lisa Havilah. The museum has half a million objects in its collection – but only 10% have ever been displayed. The 2021 program aims to showcase some of the rest. Photograph: Carly Earl/The Guardian.

Kelly Burke, ‘Everything had been on hold’: Powerhouse Museum announces program after rocky few years, The Guardian, 9 February 2021

Chief executive Lisa Havilah has faced a series of setbacks and controversies since stepping up in 2019. Now the Ultimo site can finally unveil what’s next

The Powerhouse Museum’s chief executive Lisa Havilah has endured a rocky ride since her appointment, with an insecure future facing the Ultimo site, a Covid-19 enforced lockdown and a deluge of controversy surrounding the museum’s expansion to Parramatta.

By the time Havilah stepped up, in 2019, the Powerhouse Museum was more than $3m in the red, despite receiving $28m in recurrent annual funding. In 2020 the New South Wales premier’s department delivered an emergency injection of a further $5.3m to “address the museum’s cash position” the year before.

Ultimo was still at risk, too. In 2015 the NSW government, led by Mike Baird, announced the museum would be moved to Parramatta – and it had been widely speculated the entire city site would be demolished and redeveloped.

It was only in July that NSW capitulated to public pressure and pledged to keep the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences at its city location. And on Tuesday, Havilah finally announced her first program, which had been placed on ice until then.

“Everything had been on hold until last July,” Havilah told the Guardian. “Now we’re really focused on looking at elements of the collection that have never been seen before.”

The pause from the pandemic gave the curatorial staff the opportunity to conduct an inventory of the museum’s vast collection of some half a million objects – only 10% of which have ever been displayed in the museum. Now they were able to switch from packing up to planning.

Curatorial and technical staff had just six months to trawl through the collection and put together the 2021 program, which launches with a photographic exhibition documenting the daily working life of the Snowy Mountains hydroelectric scheme between the 1950 and 1970s.

In March the museum will draw on an extensive Middle Eastern collection with Iranzamin: an exhibition of more than 100 rarely seen objects from Persia’s Qajar era (1789-1925); and in May, the Powerhouse will showcase its enormous Australian ceramics collection alongside 20 new commissions.

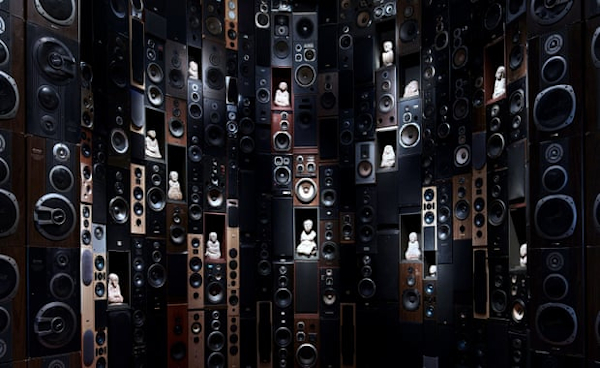

The museum’s major imported exhibition will not arrive until December: a collaboration with the Chuncheon National Museum and National Museum of Korea, which will bring to Australia some 500 arhat statues that were discovered among the ruins of Changnyeongsa Temple in Yeongwol, Gangwon-do Province in Korea, in 2001. Some are believed to be as old as 500 years; they will be displayed alongside a sound installation from Seungyoung Kim.

Historic tram depot to be retained

While the government has ensured the Powerhouse Museum will remain a city institution, the fate of the adjacent Ultimo Tram Depot – also known as the Harwood building – has been less certain.

The depot was built at the turn of last century for Sydney’s electric tramcar fleet, which traversed the city from the CBD to as far north-west as Ryde and east to Coogee. It’s a building of state significance, according to the National Trust of Australia, due to its association with a pivotal moment in Sydney: the replacement of steam trams with electric traction in 1899.

When the state government abandoned the entire Sydney tramway system in the 1950s, the Harwood building was used as a nonoperational storage facility until it was handed over to the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences in the 1960s.

But the structure has been under threat since 2015, when Baird announced the Parramatta move. Even when the Ultimo site was saved, the old depot’s future was not secured – but the Powerhouse Museum is “currently working closely with government on a business case, which [will include] the renewal of Ultimo and what the scale of that will be,” Havilah told the Guardian.

Questions still cloud Parramatta expansion

A separate controversy remains over the NSW government’s decision to press on with a second Powerhouse Museum in Parramatta.

The chosen site on the banks of the flood-prone Parramatta River continues to be a problem. Havilah says the potential flood issues have been mitigated through design modifications, but an advocacy group critical of the move, the Powerhouse Museum Alliance, have commissioned three flood risk reports so far from independent architecture and flood experts, which found the modifications don’t resolve the issue.

“The language on the flood risks is robust and unequivocal,” said alliance member and museum specialist Kylie Winkworth, who pointed to similar concerns raised by the City of Parramatta and the Department of Planning, Infrastructure and Environment.

Bringing the local community along with the Parramatta plan is presenting its own challenges, too.

The Indigenous consultants on the Parramatta project are the Deerubbin Local Aboriginal Land Council, but the traditional owners of the land recognised by the NSW government are the Dharug people, who say they are effectively being sidelined by a land council that refuses to recognise them.

While Havilah didn’t comment specifically on that controversy, she said the museum remains committed to the local area: “[At Parramatta] we’ll be looking at things like climate science, astronomy, agricultural science – and we’ll be looking at a whole range of things to tell local stories, and engage the communities of western Sydney.”

But both the Powerhouse Museum and the NSW government have remained firm on the issue of Willow Grove: it will be dismantled stone by stone and reconstructed at a yet-to-be-finalised location in the area.