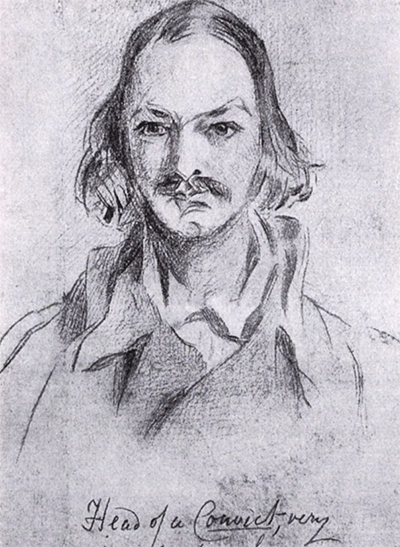

Cutmear Sisters by Thomas Griffiths Wainewright.

Luke Slattery, Not your usual convict had ‘dandy’ time in Hobart Town, The Australian, 19 November 2021

Between the First Fleet’s arrival at Port Jackson in 1788 and the ending of penal transportation eight decades later, few convicted killers lived long enough to breathe the sea air. They were swiftly dispatched, like many convicted of lesser crimes, on the gallows. But the most famous killer of that age – an ostentatious dandy, artist and art critic – boarded the convict ship Susan at Portsmouth in August 1837 and arrived at Hobart Town three months later.

The felon’s name was Thomas Griffiths Wainewright: forgery was the crime for which he was convicted and life the term of his sentence.

Forgers, paradoxically, were the young colony’s first “creatives”. Francis Greenway, the inaugural government architect, was convicted of the same crime; so, too, was Joseph Lycett, the most distinguished of early colonial artists; and Henry Savery, author of the first Australian novel.

Wainewright, though, was an altogether darker character. He was widely believed to have murdered, among others, his sister-in-law Helen Abercromby after first insuring her life for what was then the vast sum of £16,000: Wainewright was sole executor of her will and shared beneficiary. His murder weapon of choice was strychnine; the digestible bullet.

Though he and his wife Eliza were never charged with the crime, he is said to have blithely confessed to a friend: “Yes; it was a dreadful thing to do, but she had very thick ankles.” Or so reports Oscar Wilde, who wrote a short essay about Wainewright under the catchy title Pen, Pencil and Poison. Wilde was not the only Victorian fascinated by Wainewright’s duality – the horror of his crimes and the excellence of his taste; the glittering London literary circle in which he rose, and the inner rung of a living hell to which he descended.

Wainewright, who was born in a delightful villa outside London on the Thames, wore his hair long and sported a distinctive centre parting. When not wearing pale yellow kid gloves in his London years, he adorned his fingers with rings – one of which was said to contain a lethal dose of strychnine permanently, as it were, on hand.

His grandfather was Ralph Griffiths, bookseller and founder of the literary Monthly Review, and he enjoyed the patronage of the London cognoscenti. His art criticism appeared regularly in The London Magazine under the noms de plume Cornelius van Vinkbooms and Egomot Bonmot.

Charles Dickens, who as a young reporter spied Wainewright awaiting transportation at Newgate, wrote a short story titled Hunted Down based on his putative and, all things considered, likely crime. In the opinion of poet-critic Algernon Charles Swinburne he was “admirable alike as a painter, a writer and a murderer”. Swinburne finds fault not so much with his talent – his “genius” – as its application.

Conviction, transportation and exile combined to ruin Wainewright’s social standing in the imperial capital and to draw a veil over his art. He saw himself as an artist primarily and exhibited his pictures, though not his rather trumpeting published prose, under his own name.

The Susan’s convict manifest, which likely relies on Wainewright’s self-description, lists his profession as artist. Yet a recent study of the period describes him as an “art critic and poisoner”, a “writer and a murderer” – his art has been erased.

Wainewright’s artistic reputation vanished quickly on his conviction for the forgery of signatures that allowed him to withdraw £2250 from the Bank of England and his “hurried”, as he later recalled it, transportation to Van Diemen’s Land. He fell victim to a Victorian version of cancel culture: a collective urge to remove artworks (in essence a form of iconoclasm) and silence of artists.

“Complete oblivion seems already to have overtaken all that Wainewright painted,” Alexander Gilchrist notes in his 1863 Life of William Blake, whom Wainewright befriended and patronised.

“Into any of the works of such a life it is difficult to search without feeling as if every step were taken among things dead and doomed,” Gilchrist writes. He asks, however, that these works be judged apart from their creator’s deeds, for “art has its own truth, as absolute as life itself”.

Although Wainewright worked in several modes and mediums, and shows the typical interest of his age in classical literature and Renaissance art, the bulk of his surviving colonial work is small-scale portraiture in watercolour over pencil. His subjects are mostly well-to-do Van Diemonian free settlers, colonial administrators, and their families, whom he renders much as they liked to be seen: as fashionably decorous gentry.

There is no surviving evidence in Wainewright’s Tasmanian art of a Hogarthian interest in the life of the crooked lanes, or the kind of sensitivity to southern light and the grandeur of landscape that saturates the work of his Hobartian contemporary John Glover.

What was revealed in Paradise Lost: Thomas Griffiths Wainewright, a recent exhibition at the Tasmanian Museum & Art Gallery, on the other hand, was an artist of great subtlety, fluency and finesse and an unexpected generosity of spirit; the latter quality was clearly evident in his portraits of men, even if it was largely absent from his studies of women.

Two works in particular could be considered minor masterpieces.

The first is a portrait of William Bedford, a Church of England clergyman and, from 1823, ecclesiastical power in Van Diemen’s Land. Dubbed “Holy Willie” by prisoners, he was by reputation vain, rivalrous and headstrong. Bedford’s self-regard and inner conviction radiate from Wainewright’s portrait. The artist has managed to record the telltale signs of age – pouchy cheeks, puffy eyelids, double chin – together with a flatteringly ageless vitality. The mouth, though slightly downcast, remains full and firmly defined; the eyes are widely set, chin firm, brow broad. Bedford was in his early 60s at the time. There is a little flattery here and a great deal of psychological truth.

The other is Wainewright’s charming portrait of the Cutmear sisters, Jane and Lucy, executed while the girls were aged eight and nine, respectively, and Wainewright was still incarcerated. Their father, James Cutmear, the prison barracks keeper, is thought to have supplied his charge with paper and drawing materials and this small work – roughly 32cm x 30cm – was payment of a kind.

The faces of the girls, long thought to have been twins, are somewhat idealised. Wainewright gave almost all of his female figures the same swan necks, widely spaced eyes and bow-shaped mouths. Yet the artist was clearly aiming to convey loveliness and innocence in a particular and human, rather than a general and abstract, form. The sisters share the same shell necklaces and plaited pigtails, although a stray curl hovers above the left eye of the more upright of the two girls. The other, whose head is cocked into a pose of engaging alertness, has allowed a ribbon to unravel over her right ear. These subtle details help to delineate character and balance the pictorial composition.

A self-portrait of the artist is held in Britain and there it remains, but a conjectural self-portrait from a private Australian collection was included in the TMAG show. This dandyish figure has a side part, light hair, a sickly complexion and what appears to be a cleft lip. As none of these features match descriptions of Wainewright it is titled Portrait of a Gentleman.

Wainewright might never have evolved into a Blake, a Turner or a Gainsborough. But in shameful exile, in colonial Hobart, it’s possible he found his true metier as a witness to, and recorder of, the rise of a “polite” social class in a most impolite town. Yet he was no mere witness; Wainewright was, as the exhibition revealed, a fine portraitist. It’s possible that the straitened circumstances in which he worked, and the paucity of available materials, enforced the discipline his abundant talent required. He was given an unconditional pardon in 1846 and died the following year, aged 52, of stroke. His grave has never been found.