Demonstrators protesting Warren B. Kanders in May at the Whitney Museum of American Art. He resigned from the museum’s board in July. CreditCreditAndrew White for The New York Times.

Robin Pogrebin, Elizabeth A. Harris & Graham Bowley, New Scrutiny of Museum Boards Takes Aim at World of Wealth and Status, The New York Times, 2 October 2019

A recent protest at the Whitney that drummed out a vice chairman exposed the symbiotic, but potentially problematic, relationship that museums have with some trustees.

Warren B. Kanders, a vice chairman of the Whitney Museum of American Art, had just been driven out by a cascading protest over his company’s sale of law enforcement and military supplies. And his fellow trustee Kenneth C. Griffin was livid.

So hours after Mr. Kanders resigned in July, Mr. Griffin, a hedge fund titan and one of the world’s richest men, followed him out the door, quitting in outrage during a conference call with other board members.

Before lunchtime, the Whitney had lost two major benefactors — the lobby is named after Mr. Griffin, and Mr. Kanders and his wife have an adjoining stairwell.

By the end of the day, Mr. Griffin had changed his mind. But according to people privy to the events, he did so only after Leonard Lauder, the cosmetics scion and the museum’s powerful chairman emeritus, phoned Mr. Griffin from a boat to coax him back.

Mr. Griffin was not the only wealthy arts patron unnerved by what had happened — the tumult at the Whitney sent a lightning bolt through the entire museum world. If board members can be forced out because of what they do for a living, what does that mean for cultural institutions that depend on their generosity to survive?

“There is a slippery slope if you get very precious about holding out a litmus test for service on a board,” said Reynold Levy, the former president of Lincoln Center and a philanthropy expert. “This can be stretched to the point where it becomes very difficult to attract and retain board members.”

Anyone who scans the financial records of major American museums, or talks to their leaders and donors, can gauge just how much is at stake.

In the absence of significant public support, some museums rely on board members for upward of one-fifth of their annual budgets. The price of admission to the boards remains steep, often millions of dollars to enter, and annual donations of six figures to keep a seat. Those boards are also dominated, as they have been for years, by the likes of Mr. Griffin, Mr. Kanders and Mr. Lauder from finance, real estate and the corporate executive suite.

How to Find a Museum Board Seat? Start on Wall Street.

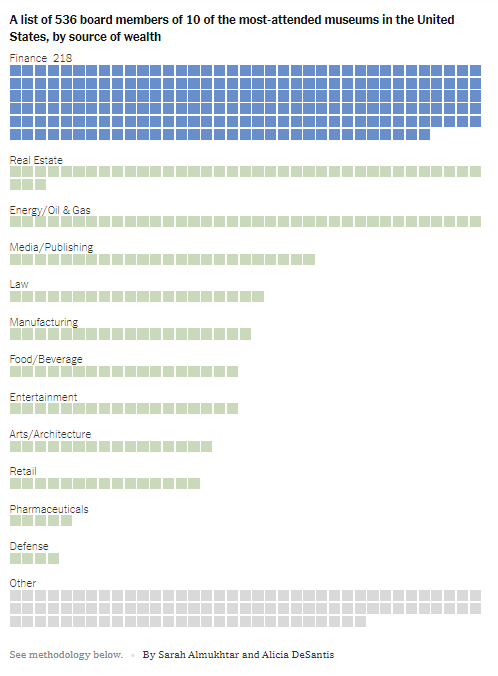

Some 40 percent of the more than 500 people who sit on the boards of America’s most popular art museums either work in the finance industry or derive their wealth from it. Many other trustees owe their wealth to real estate or profits from the energy industry, including oil and gas.

In return for their donations, board members gain admission to an exclusive cultural club others yearn to join; give arts organizations their cachet and connections; and provide a power base that commands the attention of public officials. They also get a boost in status, rare access to artists and curators as well as the public recognition that comes with giving back.

Thanks to trustees’ support, the public gets to enjoy Picassos, Rembrandts, Shakespeare in the Park.

But an emboldened activist movement is holding a mirror up to this bargain, loudly questioning whether the greater good is served, even if not everyone agrees on who and what qualifies as “good.”

The Whitney protests, ignited by a report that tear gas made by a Kanders company had been used against migrants at the southern border, started out with noisy gatherings in the museum lobby calling on Mr. Kanders to step down. As he stood his ground, the protesters became more confrontational, marching to his Greenwich Village home and posting his address on Instagram for others to find. Eventually, several artists withdrew from the Whitney Biennial in solidarity, threatening the museum’s signature exhibition. Mr. Kanders resigned soon after.

Pressure is building on other cultural institutions as well, with demands they become more representative of the communities they serve. In New York, Mayor Bill de Blasio has made city grants conditional on boards’ increasing their diversity.

Max Hollein, the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which recently swore off money from members of the Sackler family with links to OxyContin, acknowledged that “we have to be clear about how we accept donations.

But he also emphasized that the museum as we know it would not exist without the board that props it up.

“Institutions in the U.S. are built on philanthropy,” he said. “That means a significant amount of individual support.”

Dollars and sense

At the Whitney, some 10 to 12 percent of the $60 million annual operating budget comes from board contributions, a number that just begins to quantify what trustees pay for other things, like construction projects and tables at fund-raisers. In Mr. Kanders’s 13 years on the board, his donations approached $10 million.

The Museum of Modern Art estimates that its trustees contribute as much as 20 percent of its $175 million budget. At the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, officials pegged that support at about 30 percent.

“Trustees are an important part of the finances of a museum,” said Brent R. Benjamin, the director of the Saint Louis Art Museum and president of the Association of Art Museum Directors, “and their financial leadership is critical for bringing in other donors.”

Trustees can also bring with them practical benefits. Having the developer Jerry Speyer as chairman for years helped the Museum of Modern Art navigate New York City real estate when pursuing its recent ambitious building projects.