Martin Bailey, UK Government Art Collection will review 300 works relating to slavery, colonialism and racism, The Art Newspaper, 3 February 2022

The UK’s Government Art Collection (GAC) has earmarked 300 paintings and prints that are due to be reinterpreted, mainly over issues relating to slavery, colonialism and racism. Each item was tagged on their website: “Interpretation about this artwork is under review”.

Following questions by The Art Newspaper, these tags were immediately removed from the website early last month. A spokesperson for the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), to which the GAC belongs, says they had been tagged in error.

The spokesperson explains: “Due to an administrative error a number of paintings on the Government Art Collection website were incorrectly stated to be under review. This is not the case and the website has now been corrected.”

The tagged works included 26 portraits of Queen Victoria. Among the buildings in which they currently hang are British embassies and diplomatic missions in Berlin, Istanbul, Kathmandu, New Delhi, Paris, Rome, Stockholm, Tehran, Tokyo and Tunis, as well as the Cabinet Office and Lancaster House in London.

Although slavery in most of the British Empire had been formally abolished in 1833, four years before the queen’s accession, the system had not been entirely ended before she was crowned. Under Queen Victoria’s reign, imperial rule was expanded, usually by force, and she was made Empress of India in 1876.

Other GAC portraits of British monarchs earmarked for reinterpretation include those of Elizabeth I, Charles I, Charles II, William III, Anne, George I and William IV. Some of these kings and queens were involved with the Royal African Company, although inclusion may also have been due to an artist or patron being involved in questionable activities.

Two portrait prints of George Washington were tagged. Again, they may have been earmarked for reinterpretation because of the artists or patrons.

Some works are obvious candidates for reinterpretation. William Müller’s The Slave Market (1842) depicts a scene in Cairo, involving Arab rather than British buyers. This watercolour was bought by the GAC in 1964.

George Bickham’s How to get Riches (about 1736) depicts several sailing ships with an inscribed poem. Singing the praises of British traders, the poem includes the line: “New Lands to make, new Indies to explore”. Perhaps surprisingly, this historical item was bought as relatively recently as 1978.

There are 13 works relating to Jamaica, most of them early landscape prints. These include a pastel portrait by John Russell of Thomas Millward (1796), who owned a coffee plantation on the island. In the portrait Millward prominently holds a book recording Jamaican laws, which has a section on dealing with slaves.

The GAC’s Jamaican works include a lithograph by Joseph Kidd of Cocoa Nut Walk on the Coast near Runaway Bay in Jamaica (1838-40). The origin of the place name remains uncertain: the bay was named either after escaping slaves or the Spanish governor who fled the British in 1670.

Rethinking Rhodes

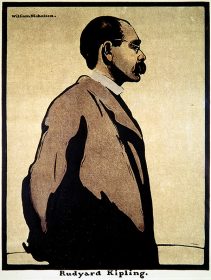

Two William Nicholson prints (1899) are due for reinterpretation. These depict Rudyard Kipling, author of the jingoistic poem “The White Man’s Burden”, and Cecil Rhodes, who energetically promoted imperial rule in southern Africa. Edward Lear’s three landscapes of Ceylon (Sri Lanka) are also included (1870s-80s).

As the GAC website explains, it is currently “reviewing interpretation about artworks and reappraising how they have been considered historically”. This is part of a much broader exercise that is taking place in most major UK museums, an initiative that has assumed greater importance since 2020 with the Black Lives Matter movement.

But what is new is that the GAC is no longer publicly identifying individual artworks that will be subject to possible reinterpretation.

In an article in The Art Newspaper on the GAC works that the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rishi Sunak, had chosen for 11 Downing Street, we highlighted Arthur Kampf’s Portrait of Cecil Arthur Tooke (1918), a work depicting a British prisoner of war painted by an artist who went on to later became a favourite of Hitler.

Following our report on this eclectic selection of paintings, the issue was taken up by the Daily Telegraph, which wrote that “dozens” of works were being subject to reinterpretation.

As we can now reveal, the actual number is far higher, around 300 (out of the GAC’s total of more than 14,000 works).

Although the UK government started to collect art systematically in 1899, some works had been acquired in the 19th century, during the height of the British Empire. These early acquisitions obviously reflect the ethos of the time. The GAC in its present form effectively dates back to 1946, with the appointment of its first curator.

Although the DCMS spokesperson would not comment further, it seems that the GAC—part of the department—is awaiting government guidance on “contested heritage”.

Last May the then DCMS secretary of state Oliver Dowden established a Heritage Advisory Board “to oversee the development and drafting of a new set of guidelines on how difficult heritage assets should be dealt with”.

Dowden stressed the importance of the need to “retain and explain”. Statues and art should not be removed, but kept, with appropriate explanations, so that we can learn from history.

The GAC, which has museum status, has its core work funded by central government. The official line is that the GAC “promotes British art and plays a key role in British cultural diplomacy, delivering an expression of Britain’s soft power, its culture and its values”. As such, it is important that works which could possibly offend are properly explained.

Reinterpretation of the GAC works is expected to be eventually completed after receiving the guidance of the Heritage Advisory Board. Presumably, data on individual works will be inserted on the GAC website and in briefing material at the places where the works hang—mainly government buildings in the UK and diplomatic missions abroad.

It seems that in the short term the GAC will probably not remove works that currently hang in official premises. But since works are often moved, it will be interesting to see whether the more sensitive ones are gradually retired into storage, to be replaced by others that do not raise sensitive issues.