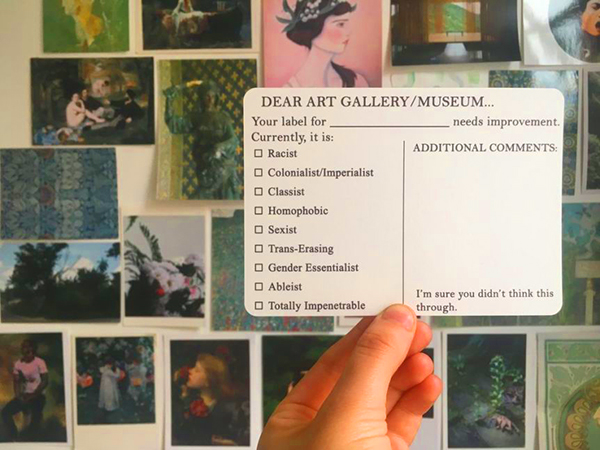

Alice Procter writes and talks about histories of imperialism, nationalism and racism in museums and galleries.(Supplied: The Exhibitionist).

Hannah Reich, Art historian Alice Procter is on a mission to decolonise museums and galleries in her ‘Uncomfortable Art Tours’, ABC News, 14 May 2020

When you wander around a museum or a gallery, how deeply do you think about the legacy of historical artifacts and objects that are on display? Do you think about how they were acquired?

Or, how about how an object is displayed? How it is lit, or located, or labelled?

These are the kinds of questions that plague Alice Procter — a London-based Australia-raised art historian with a masters in anthropology, who curates exhibitions, makes podcasts and publishes under the name The Exhibitionist.

“The history of British art is also the history of empire and genocide, written by collectors who traded in landscapes and lives,” Procter writes on The Exhibitionist’s website.

A need to make that history more widely known led her to begin her “Uncomfortable Art Tours”: independent, guided tours in the public museums and galleries of London.

In those tours, which the Daily Mail has disparaged and which were called “sensationalist” by a British MP, she speaks about the hidden and dubious origin stories of both the institutions and the objects within them, highlighting histories of imperialism, nationalism and racism.

“They were intended to be uncomfortable in that we touch on all the subjects people think of as sort of a little bit taboo in an art gallery,” Procter told RN’s The Art Show.

“I’m not saying people shouldn’t enjoy museums … But at the same time, you’ve got to learn how to ask questions.”

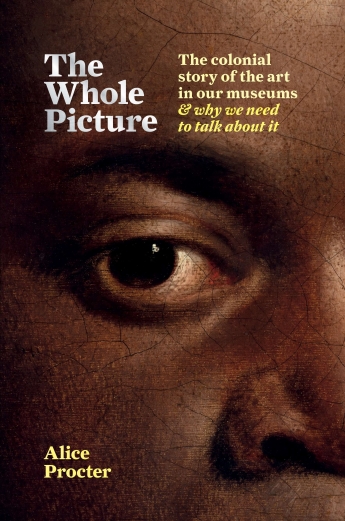

Now Procter has taken her tours to the page in a new book — The Whole Picture: The colonial story of the art in our museums and why we need to talk about it.

Exclusionary spaces

“I started my tours from a place of frustration. I had just spent three years on an art history degree that overwhelmingly ignored the colonial and imperial history that created the museums and galleries we were studying,” Procter writes in The Whole Picture.

The first Uncomfortable Art Tour she ran was in June 2017, as part of the Antiuniversity Now festival — and she’s run them ever since.

“I was able to get away with running my tours, essentially undercover, for nearly a year because the museum staff would look at me and think I was an official guide,” Procter says.

“I’m a nice white girl with an art history degree who looked the part and sounded the part.”

Procter wants to break the “hold” museums have over us and look at who actually feels comfortable in these spaces.

“When museums are invented, they’re invented to be spaces that are exclusionary and exclusive. And that means that they’re very racist and very sexist right from the beginning,” she says.

In her book, Procter explains that the first museums emerged from the private collections of wealthy individuals (the British Museum’s foundation collection belonged to Sir Hans Sloane) and were therefore based on those individual’s tastes, values and politics.

“Whether you’re deliberately collecting with a political agenda or not, you’re collecting in a political world. And so it’s always going to reflect that kind of status and worldview that you’re part of.”

She writes that curators, who still skew white and privileged, are continuing to determine what we value through what they collect and how they display it.

The Gweagal Shield

In The Whole Picture, Procter hones in on certain objects within collections and museums — for example, the British Museum’s Parthenon marbles.

But she says “the objects that we most need to spend time with, right now, are often the ones of first encounters and first contacts” between Indigenous peoples and European colonisers.

“[Those objects] are representing the kind of creation of colonial power,” the art historian says.

One example is the ‘Gweagal Shield’, an oval shaped shield made from red mangrove wood, which dates to 1770 when Captain Cook and Sir Joseph Banks arrived in the area now known as Botany Bay.

In that moment of first contact with the Gweagal clan of the Sydney area Cook shot one of the Gweagal men, who then dropped his shield before fleeing.

“[The shield] becomes the first relic of south-eastern Australian Indigenous culture that makes it to the UK,” says Proctor.

It was first displayed in Banks’ private museum and then the British Museum, where it has been referred to as the “Cook Shield”.

“Its history has always been about this myth of … this perfect continent waiting to be conquered and discovered,” Procter says.

The shield’s history has been subject to research and debate, and Rodney Kelly, a Dharawal and Yuin man who is a descendant of the Gweagal warrior Cooman — the man who used the shield and was shot by Cook — has long been campaigning for it to be repatriated.

Procter says the British Museum’s explanatory label on the shield reduces a contentious and complicated history to this one sentence: “First contacts in the Pacific were often tense and violent.”

Restitution and representation

Before COVID-19, Procter was running Uncomfortable Art Tours a few times a week at six London sites, including the British Museum, the National Gallery, and Tate Britain.

Fine art and art history students were her first tour attendees, but now whole university classes and museum staff attend her sold-out tours (which cost $13–$20).

“Most of these institutions recognise they’ve got problematic histories,” Procter says.

“A museum knows that it’s got a contested object in the collection because the museum staff are the ones that are cataloguing and researching.”

She wants museums and galleries to “display it like you stole it” and make the acquisition history of objects transparent.

When it comes to restitution of objects to their original communities, she says decisions must be made on a case by case basis.

“But overall, and overwhelmingly, I’m massively in favour of restitution,” Procter says.

“When you return an object to its community of origin or the descendants of its community of origin what you’re doing is acknowledging that they have a kind of expertise that you can never imitate,” Procter says.

She says her work as an outsider is enhanced by those working inside institutions to create change; she appreciates the work of UK groups Museum Detox and Museum as Muck, which provide support to museum workers from marginalised backgrounds

The tipping point

Procter says that in the UK there’s been “an amazing shift” amongst smaller museums and university collections towards the repatriation and restitution of ancestral remains and sacred objects.

Among these are London’s Natural History Museum, Oxford University’s Pitt Rivers Museum, and the University of Manchester’s Museum, which has recently agreed to return 43 items belonging to four language groups across Australia.

There is an ongoing process of repatriation of Aboriginal ancestral remains happening in Australian museums too.

“This isn’t a new conversation by any means. There’s been some amazing work in Australian museums, particularly led by Indigenous educators and activists and curators,” Procter says.

This group includes Nathan “Mudyi” Sentance, a project officer in First Nations programming at the Australian Museum, and others who are working towards better storytelling around the objects, bilingual labels, and curation by communities.

Another key part of Procter’s vision of a “decolonised museum” would be a flexibility within institutions to make corrections when mistakes are pointed out.

She thinks we’re at a “tipping point”: “suddenly, someone decided that it was now in the public interest to have these conversations.”

This shift extends to who goes through the doors, with new accessible tours being introduced at many museums, and Procter says many museums are considering ways to diversify their audiences in terms of age, socio-economic background and race.

She says these institutions have been “resting on this idea for the last 300 years that we represent the world and we represent our community”.

“But actually, we should probably be doing some work to make sure that that so-called community is real.”

“We have this quite exciting chance to think about what kind of stories museums tell, how they serve us, and how they represent … national identity,” she says.

“When it comes time for these museums to reopen, I really hope people will actually take advantage of the fact that we’ve almost had a bit of a reset.”

The Whole Picture is out now through Hachette.