Belinda Smith, The story of Halford’s ‘flute boy’, and what it tells us about the European trade in human remains, ABC Science, 18 April 2021

At the height of the French Revolution in the late 1700s, a boy sat on the steps of the Notre Dame cathedral playing a lilting tune on his wooden recorder.

Parisians hurried by, occasionally casting a glance towards the child, perhaps throwing a few coins his way.

But what may have caused them to stop mid-stride was the sight of his legs — or, rather, leg. The boy’s two thighs were fused at his knee and his leg ended in a single foot.

Legend has it he died aged 28.

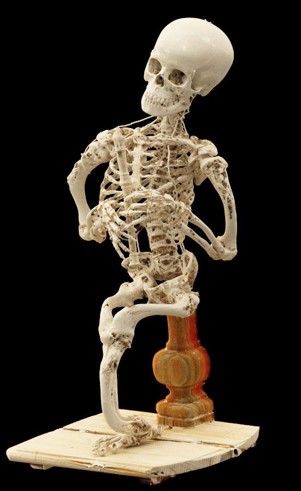

More than 200 years on and half a world away, his skeleton — a bit over 70 centimetres tall, perched on a pedestal, still grasping his wooden recorder — sits on a shelf in a storage room underneath the University of Melbourne’s Harry Brookes Allen Museum of Anatomy and Pathology.

But the vivid, lively story of the “flute boy’s” life — that he was a beggar who played his wooden flute in revolutionary Paris to the delight of passersby — is in contrast to a much darker, ethically dubious history of human anatomical specimens.

Anatomy’s rise

People have, for thousands of years, studied anatomy.

An ancient Egyptian medical text, called the Edwin Smith Papyrus after an American Egyptologist and antiquities dealer, is almost 3,600 years old.

It details nearly 50 medical case histories, such as fractures and tumours, starting at the head and descending anatomically from there.

The Greeks, too, wrote many anatomical texts. They also started what’s thought to be the first school of anatomy roughly 2,300 years ago.

But the study of anatomy really took off in Europe in the 1600s and 1700s. Anatomists dissected human bodies and, thanks to the printing press, anatomical drawings — some by famous artists such as Michelangelo — could be published and disseminated.

Along with highly detailed illustrations came a demand for physical specimens. But these weren’t the classic skeletons you might see in classrooms today, suspended from the top of the head with arms and legs dangling.

They were needed for dissection and display, especially the more out-there examples, where people lived with extreme physical disabilities or conditions.

So began a thriving trade in human anatomical specimens.

Like the flute boy.

European trade in human remains

Most of what we know about the flute boy’s life is relayed in an 1868 paper written by the man who brought the skeleton to Melbourne, says Anneliese Milk, who researched the specimen’s history as part of a master of art curatorship in 2013 and 2014.

The man was George Halford who, in the mid-1800s, was considered one of the most promising anatomists and physiologists in England.

In 1862, he accepted a job at the University of Melbourne — an institution then only eight years old — to be its first professor of anatomy, physiology and pathology.

“And just prior to him leaving the UK for Australia, he was given a cheque for 500 pounds, with the idea of purchasing books for a library and specimens for the establishment of a museum,” Ms Milk says.

“That’s when he would have purchased the skeleton.”

Yet despite anatomy’s popularity at the time, strict laws in the UK forbade the preparation of local anatomical specimens.

Under the Murder Act of 1752, UK anatomists and surgeons could only access bodies of executed murderers.

But across the channel, those laws were more relaxed. As well as executed criminals, French anatomists could dissect unclaimed bodies from, for instance, psychiatric and charitable hospitals, Ms Milk says.

So Professor Halford went through a London-based dealer who specialised in sourcing prepared skeletons.

A prolific anatomist named Jean-Joseph Sue prepared the skeleton some years earlier, and his family sold it to the London dealer in 1862.

Of course, the law did not stop less scrupulous physicians in the UK from paying bodysnatchers for fresh corpses dug from graveyards, or — in some cases — people who were killed specifically to be sold.

So to quash the bodysnatching trade and give the UK a leg-up in advances in anatomy — in which it was lagging behind the rest of Europe — the Anatomy Act was passed in 1832.

This gave doctors and medical students in the UK free licence to dissect donated corpses.

Teaching tools or talking points?

As human remains were collected and sold around the world, a market emerged for more severe examples of disease and injury.

And not just as teaching tools, either. They were often bought by the wealthy and proudly displayed in their home.

The flute boy was, without doubt, built to attract attention. Everything about him — his skull, jauntily cocked to the side, arms holding his recorder to his mouth, and that fused leg — catches the eye.

Even his seat is intriguing: a carved wooden pedestal that could have come from an ornate piece of furniture.

You can picture him sitting on someone’s mantlepiece.

But is he all he seems to be?

The skeleton, held together by nails and wire and patched with plaster and papier mache, is coated in a thick layer of brown varnish.

Chris Briggs, then an anatomy lecturer at the University of Melbourne, had doubts as to the authenticity of the skeleton: not that it wasn’t made of human bones, but that it may be made of more than one human.

He asked Chris O’Donnell, a radiologist at the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine, if he’d be interested in scanning the skeleton to see what was underneath all those layers of filler and varnish.

“And I said of course — I’d love to,” Dr O’Donnell said.

That’s partly because Dr O’Donnell had seen the skeleton before, some 40 years prior, when he was studying medicine at the University of Melbourne.

He’d never really forgotten it.

And when they put the skeleton in the CT scan, the high-resolution, 3-D X-ray images showed Dr Briggs’s suspicions were correct.

The skull and spine appeared to belong to a child, as evidenced by the set of adult teeth still ensconced in the jawbone.

But analysis of growth plates in the long bones of the arms and leg showed they were from an older person, at least in their late teens.

So the flute boy was looking more like flute boys.

And that’s if they even were boys.

“We don’t have any specific evidence of male or female — we don’t see any genitalia, for example, so we can’t tell that way,” Dr O’Donnell says.

“We don’t have DNA to look at X and Y chromosomes.

“So we’re just relying on the shape of the bones or the size of the bones [but] these are bones that are quite abnormal-looking … so those normal patterns that you would look for to see whether it’s male or female aren’t obvious.

Disease in the bones

The flute boy’s most striking feature is its single leg, where two femurs or thigh bones bend and join at the knee. Descending from the single kneecap is a set of shin bones — a tibia and fibula — and a whole right foot.

It’s said to be an example of sirenomelia, a condition that affects the development of organs of the lower abdomen, pelvis and legs, and is thought to happen in only one in 100,000 pregnancies.

It fuses the legs, which is why it’s sometimes called mermaid syndrome.

But the condition is so severe it usually kills in the womb. For babies that survive birth, they must endure several operations to separate their legs and fix malformed organs.

“And they usually don’t survive, but some do occasionally,” Dr O’Donnell says.

Another condition evident from the curved leg and arm bones is rickets — a vitamin D deficiency which was, unlike sirenomelia, common in the 18th century.

So if the young person who had the flute boy’s leg did indeed live into their late teens — in the 1700s, no less — it would be nothing short of a miracle.

While the scans showed the fused leg could be evidence of sirenomelia and rickets, it could also be possible that the person was born with two legs, and their curved femurs allowed the Parisian anatomist to exercise a little artistic licence, lose a shin, and instead create a skeleton with a single leg.

And perhaps he added the flute and invented the story to go with it, knowing it might fetch a higher price.

A life after death

Whether the skeleton shows sirenomelia or not, such specimens are incredibly hard to come by these days.

Medical knowledge has progressed to the point where some of the conditions that would have caused such severe disability, not to mention pain and suffering, can now be easily treated, says Rohan Long, curator of the Harry Brookes Allen Museum.

And in the 1700s, anatomists injected much more flair into specimen preparation. Skeletons were often assembled in a lifelike pose, sometimes with a prop or two.

Indeed, Ms Milk says, the flute boy’s musical instrument may be a bit of an anatomist’s joke. The Latin for flute is tibia, which is also one of the shin bones.

“I think that it’s one of those things that they got kind of embarrassed about it in later years, and they got rid of all the specimens … they’d moved on from that sort of thing [and thought] ‘we’re too serious for that sort of stuff now.'”

For now, at least, the flute boy will remain in its climate-controlled storage room, where it’s protected from the vibrations rumbling from tunnel drilling works out the front of the building.

But once it’s safe to do so, the precious skeleton will be brought back up to the museum, where it will once again sit in a glass case in the middle of the room, perched on its pedestal, recorder raised to its smiling skull, frozen in time.