Julian Meyrick, Robert Phiddian and Tully Barnett, What matters? A book about value in Australian culture, Limelight, 22 August 2018

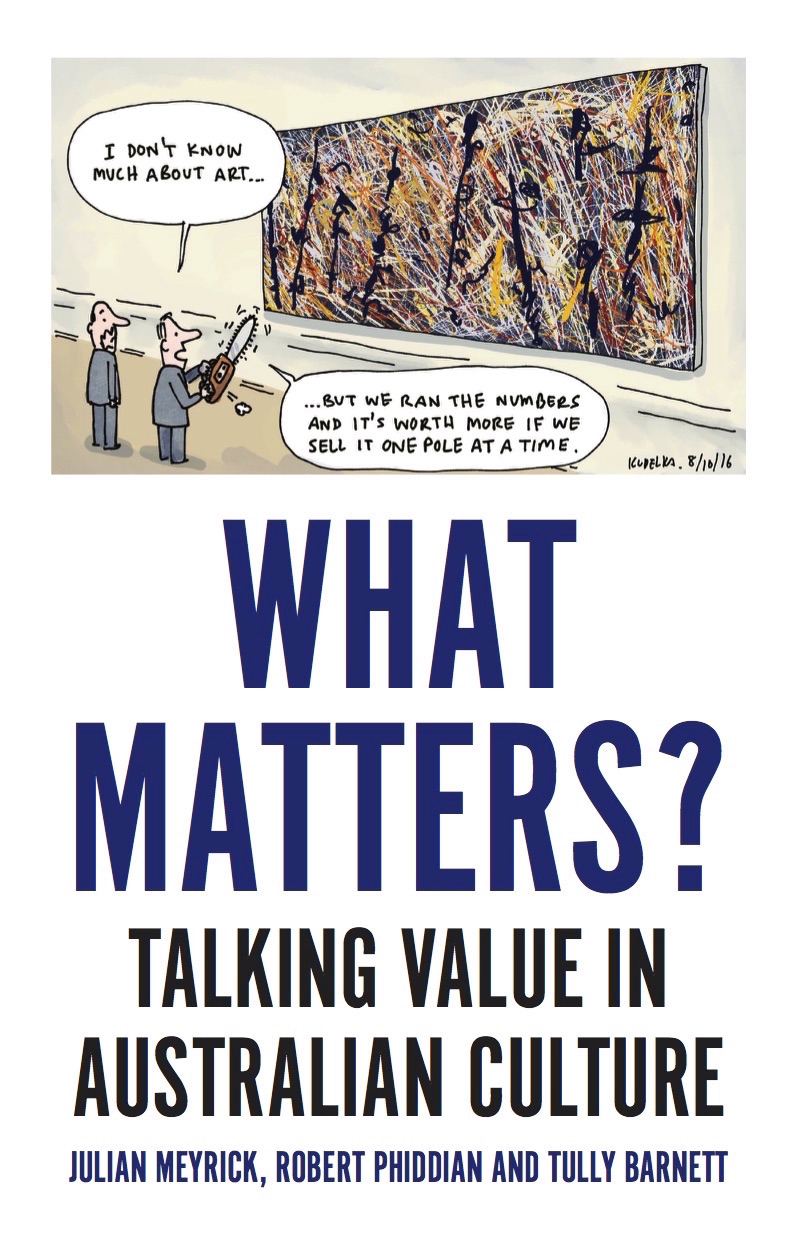

Three Flinders University scholars have written a new book about the “metric madness” surrounding the way we value Australian culture. We publish an extract.

When did culture become a number? When did the books, paintings, poems, plays, songs, films, games, art installations, clothes, and all the myriad objects that fill our lives and which we consider cultural, become a matter of statistical measurement? When did the value of culture become solely a matter of the quantifiable benefits it provides, and the latter become subject to input–output analysis in what government budgets refer to as ‘the cultural function’? When did experience become data?

Perhaps a more important question is why did it happen, and why does it keep happening? Also, how does it happen? Culture is innate to being human. Thick books have been written describing culture’s myriad expressions and meanings. Culture has been around for as long as humanity itself. And the question of its value is not new. We cannot claim the modern world is answering it exclusively. But why are we answering it in the way that we are – by turning it into something to be scaled, measured and benchmarked? Who loses and who gains?

These are big questions of more than academic or Australian import. They are, indeed, much broader than arts and culture, as a recent crop of studies describing the unintended effects of the rise of ‘metric power’ suggests. So our modest book based on local experiences will nevertheless be of interest beyond Australia and the usual suspects of the cultural debate. Our core contention is that datafied modes of analysis are claiming authority over domains of human existence they have limited capacity for understanding. If you are researching an influenza epidemic, more data is better data. If you are studying Australian film, more data is informative but not definitive because questions of artistic merit can only be judged. If you are assessing Christina Stead’s The Man Who Loved Children, massified data is close to useless.

At a time when even accountants are looking for a more compelling understanding of value, it is imperative that the arts – a domain where individual experience is central – resist the evangelical call of quantification, and winnow its potential benefit from its real and deleterious risks. Our book addresses anyone seriously interested in the value of arts and culture. It particularly addresses those with an operational interest: arts practitioners, managers of cultural organisations, policy makers, leaders of cultural programs at all levels of government, philanthropists and board members, critics (within and outside the academy) and so on. We hope to influence public debate about the value of culture, to encourage people to see their cultural experiences in that debate, and not feel some strange urge to ‘speak the language of government’.

In 2013, we began a university research project of moderate scope seeking to understand how quantitative and qualitative indicators align in government measures of culture. As we were in Adelaide, we made that city our focus. To get our research off the ground, we held a lunch for some of Adelaide’s cultural leaders. Over dessert, we asked them what they wanted us to achieve. The answer was instructive: a way to talk truthfully about what they do. They were, they said, unable to incorporate their real motivations and experiences into their reporting. Could we find a new, better way of communicating the actual value of arts and culture?

For the first year this seemed a simple enough goal. After all, these people were doing things the public had ready access to. Both state and local government in South Australia had a record of acknowledging the contribution of culture. They supported a range of cultural organisations and events – especially festivals, which are a big part of Adelaide’s civic life. There was a sense that everyone already knew how important culture was to the state. But when it came to demonstrating its value, the words weren’t there. Our job was to fix that. As humanities scholars, we felt we were in a good position to do so. After all, didn’t we spend our lives talking about culture?

As the second year drew on, a note of uncertainty entered the project. By now we were starting to publish, and articulate in a series of articles, columns, notes, letters and emails, the dimensions of the problem as we saw it – the short time-scales governments deploy to evaluate outcomes, for example, which ignore culture’s longer-term contribution. Or the woolly use of language in policy documents, that makes the precise meaning of terms like ‘excellence’ and ‘innovation’ impossible to pin down. These issues, and others, have serious assessment implications. But it goes beyond this, highlighting a basic misapprehension of culture by governments, not on a human level – politicians and policy makers, like the rest of us, read books, watch films and listen to music – but on the official level. Their grasp of culture may be a sure one, personally. But when it comes to acknowledging that value publically, government measurement strategies, like those of Adelaide’s cultural leaders, seem to fall forever short of the requisite level of proof.

Use of measurement indicators assumes a degree of background understanding that too often isn’t there at a policy level. The quantitative demonstrations of value we were trying to improve don’t make sense for culture. They flatten out its history, purpose and meaning. This realisation put us at odds with expert views about the role of culture in post-industrial societies today. These views are typically upbeat about culture’s economic and urban ‘vibrancy’. Charles Landry’s ‘creative cities’, Richard Florida’s ‘creative class’, John Hartley and Terry Flew’s ‘creative industries’ – the ideas of these authors, and others of similar ilk, are practical and positive (though Florida has recently retreated to a gloomier position). This chipper outlook is mirrored by swarms of local efforts around Australia today to develop bespoke systems of ‘cultural indicators’, each slightly different, yet each beholden to the same underlying assumption: that the value of culture can be numerically demonstrated. We sat through presentation after presentation on quantitative approaches to culture’s value. At the end, hands would invariably go up and people say they were developing a ‘similar measurement model’.

Yet underneath the relentless optimism, we sensed a current of troubled preoccupation. It went by different names: ‘the intrinsic value of culture’, ‘the inherent value of culture’, ‘(the) cultural value (of culture)’. In this dry form it seems just another dimension of culture’s value, to be arraigned alongside the others: its economic value, its social value, its heritage value, etc. It is not. It is code for all that is left out of measurement indices, which is to say our whole sense of culture, of what culture means. It seems obvious to say it, but in culture No Meaning = No Value. It may not be true of boots, bread and billiard balls. But it is absolutely true of symbolic goods like paintings, performances and books.

This was the problem of culture’s value as it appeared to us in our third year, when we saw the full extent of what we had stumbled into. Beneath the inexorable pursuit of numbers-driven data lay a Dante-esque vortex of hope, despair, panic and bewilderment masked by the neutral patois of quantitative analysis – the bullshit language that Adelaide’s cultural leaders resented so deeply. In contemporary assessment processes, many arguments can be advanced for culture’s value, but culture itself is not an argument. It is like asking someone to justify transport but forbidding any mention of cars. The bullshit has to be all about fuel sales, industrial development and urban expansion.

This is an edited extract from What Matters? Talking Value in Australian Culture by Julian Meyrick, Robert Phiddian and Tully Barnett, published this month by Monash University Press

See also: Beyond Bulldust Benchmarks