Catherine Speck, Who gets to be political in Australian art?, The Conversation, 14 March 2025

When the invitation for artist Khaled Sabsabi and curator Michael Dagostino to represent Australia at the 2026 Venice Biennale was rescinded, the statement from Creative Australia’s board said their selection now posed “an unacceptable risk” and “could undermine our goal of bringing Australians together”.

This is at odds with the 2023 cultural policy Revive, which stresses inclusion, cultural diversity and increased participation from under-represented voices.

Sabsabi had been criticised for two works.

You (2007) features a sophisticated manipulation of images – loaded with ambiguity – of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, well before the organistion was proscribed as terrorist.

Thank You Very Much (2006) is an equally ironical work consisting in 18-second video montage of the 9/11 World Trade Centre attacks overlaid with imagery of George W Bush thanking the American public prior to launching devastating attacks on the Middle East.

These are nuanced works, produced 20 years ago in differing political circumstances, and previously shown without critique. They have been taken out of context and misunderstood.

At the same time as this controversy unfolded, it was revealed the National Gallery of Australia requested permission from curator Rosanna Raymond and the Indigenous SaVAge K’lub art collective to cover up the Palestinian flags in their larger tapestry on display. Raymond is still shocked that such a step was taken.

Surely this runs counter to the imperative in the nation’s cultural policy Revive, to provide “a place for every story”.

Australian artists have long featured political figures or political statements in their work. Who gets to be political in Australian art?

‘Pragmatism of cruelty’

Civil society is built on freedom of expression. At certain times artists, steeped in ideas of the avant-garde but with a contemporary inflection, feel an urgency to respond to cultural fissures.

The Vietnam war was one such fissure.

In the early 1970s Australian society was divided over participation in this American-led war, and Moratorium marches were held across the nation.

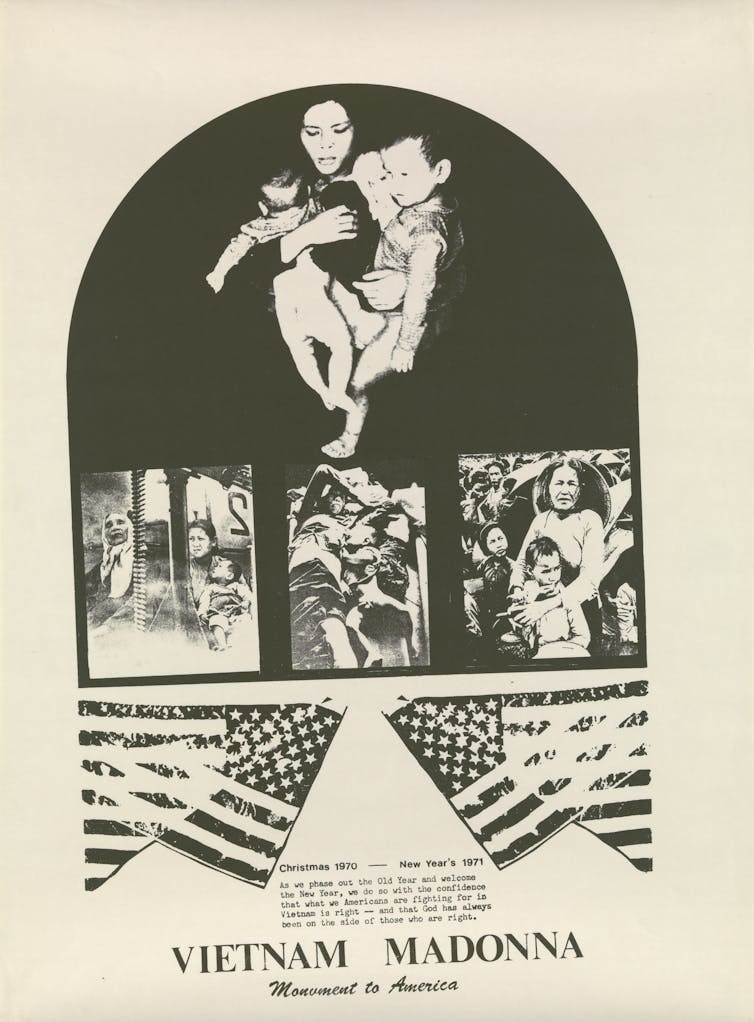

Ann Newmarch, a member of the radical Progressive Art Movement (PAM) opposed to American imperialism, focused on the Vietnamese women caught up in the conflict.

In her evocative Vietnam Madonna (1975), she portrays a mother trying to protect her children.

This was a PAM poster, produced to be widely distributed. Its anti-American message merged with feminist statements about motherhood was easily understood. It was hung in students’ quarters, artists’ studios and factory canteens.