Cosplayers in character as The Joy of Painting TV star Bob Ross at MCM London Comic Con 2019 at ExCel on October 26, 2019 in London, England. (Photo by Ollie Millington/Getty Images).

Ben Davis, Bob Ross May Have Been the Most Popular Artist of 2020. Here’s Why It’s Not Just a ‘Happy Little Accident’, ArtNet News, 30 December 2020

Here are five reasons for his persistent—and growing—popularity.

Because it is a fun thing to talk about at the end of a monstrous year—and because there are actually things to say about the phenomenon—I thought I’d close the year by writing about the present-day Bob Ross Renaissance.

2020 was a bad year in almost every way imaginable, but it was a good year for the late PBS star. For one, the “Bob Ross Experience” opened in Indiana, where you can be immersed in the artist’s work and paint along with him and teachers trained in the Bob Ross Method. A New York Times reporter even penned an essay about the transformative effect that the experience had on her.

Whatever your preferred channel of consuming culture, there is a Bob Ross option for you. A standalone Bob Ross Channel launched on TV. The Greater Cannabis Company announced a line of Ross-themed “beauty and cosmetics products.” If you’re a Bob Ross-loving gamer, you had the choice of acquiring a Bob Ross Monopoly set or a new Bob Ross-themed expansion pack for Magic: The Gathering. All of these launched this year.

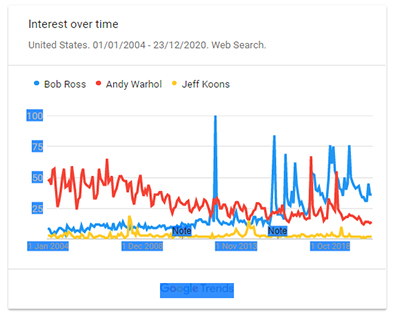

Last year, the painter who once modestly said that his art would never be shown in the Smithsonian actually made it into the Smithsonian, which acquired a handful of his paintings. I don’t think it’s inaccurate to say that Bob Ross is now, by some measures, the most famous postwar American artist—and his fame has actually increased in the recent past. It was only in the last half decade that interest in him (in terms of web searches at least) surged past Andy Warhol on a consistent basis.

Odd as it may seem, I think Bob Ross’s offbeat afterlife has something to tell us about what’s happening in The Culture.

Bob Ross conjured his woozy landscapes from a palette of named colors that he encouraged you to see as distinct entities with distinct powers, from Titanium White to Van Dyke Brown. Similarly, the Bob Ross Renaissance is formed from a number of discrete energy streams that are flowing through visual culture as a whole, and you can name them individually.

Edgeless Culture

Think pieces trying to grapple with Bob Ross’s tenacious appeal—like this one from the Atlantic, or this one from Frieze—inevitably start here: He is a soothing, non-judgmental presence in a world that has felt very turbulent and polarized in recent years. He is, in this sense, an avatar of “edgeless culture”—as in, the opposite of edgy culture.

Scan the Bob Ross news of the last year and you’ll find any number of articles that start with “this is what we need right now.” A general therapeutic language has entered cultural writing, which Ross’s persona chimes with: “If painting does nothing else for you, it should make you happy,” he once said. The resurgence of interest in the artist belongs to the same cultural moment as the new interest in another PBS star and avatar of general kindness, Mr. Rogers.

Ross’s appeal is thus not just a throwback. It’s riding a larger, very contemporary zeitgeist. Earlier this year, on The Cut, writer Molly Fischer described the “millennial aesthetic” in art and design as a return to sincerity after hipster irony; the invocation of a lot of self-help, self-care, and slogans of affirmation; and the domination of soothing colors, soft lines, and unthreatening subject matter.

Well, that is like a word cloud describing the Bob Ross persona. A happy little word cloud.

The Power of Presencing

Bob Ross’s signature perm is more famous than any of his paintings. “As much as he loved oil and canvas, his true resonance is with the screen,” Michael J. Mooney wrote in the Atlantic. Again, this resonates with a more general cultural development.

Karen Patel describes what she calls the “pressure to presence” for contemporary artists, that is, the emerging—or, really, now fully emerged—imperative that artists not just create art, but maintain and cultivate a media persona around their art. Instead of showing finished works, artists building a following on social media are often advised to post in-process images to show a work coming together or to show themselves in the studio, as a way to cultivate a sense of intimacy and connection with their audience.

It’s fitting, then, that Bob Ross would be such a big star in the social media age. He is the example of how the fascinations with the artist as low-key media star and with painting as a process have magnetism of their own—probably outshining the final power of his actual completed paintings.