Wrasses dazzle: how fairy wrasses got their flamboyant colours, The University of Sydney, 1 March 2021

Coral reef fish diverged in ‘evolutionary arms race’ during last ice age

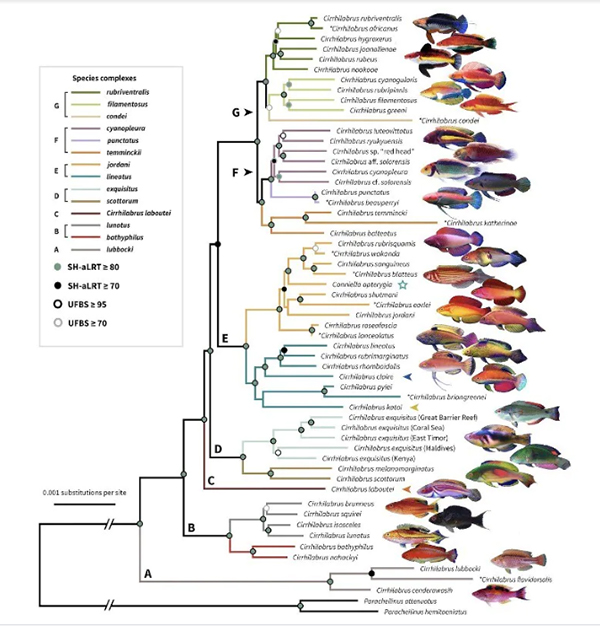

Sea level rises and falls during the Pliocene/Pleistocene epoch acted as a ‘species pump’, propelling fairy wrasses across oceans, and allowing them to evolve separately, into the 61 (and counting) species that exist today.

Fairy wrasses diverged in form and colour after repeated sea level rises and falls during the last ice age, finds a new study. Published in top journal Systematic Biology, it employed a novel genome-wide dataset to make this discovery.

Lead author, ichthyologist and PhD candidate at the University of Sydney, Mr Yi-Kai (Kai) Tea, says that the fish’s divergence occurred rapidly and over a short amount of time.

“Although the fairy wrasses split from their most common ancestor some 12 million years ago, it was only within the last 2–5 million years ago that much of their divergences took place, in the Pliocene/Pleistocene epoch,” said Mr Tea, a researcher in the School of Life and Environmental Sciences.

Repeated sea-level fluctuations acted like a species pump, propelling fish into the Indian Ocean and even as far as the Red Sea

Mr Tea completed the work under the supervision of Professors of Molecular Evolution, Simon Ho and Nathan Lo.

Decoding fish DNA

Despite the vast variation in colour and form, many species of fairy wrasses have highly conserved, or similar, regions of their genome. This poses a challenge in trying to reconstruct their evolutionary history.

The current study used an approach that had not been previously attempted on fairy wrasses: by combining genome-wide ultra-conserved elements with mitochondrial DNA, the researchers reconstructed a robust evolutionary tree. Using that, they began to tease apart the reason behind the fish’s diversification.

Do a little dance, make a little love

In addition to sea-level fluctuations, male fairy wrasses (as with many animals, the more colourful sex) developed their bright colours and individual forms to court females.

“They do a little dance, and they are capable of changing colours, sometimes temporarily flashing bright, iridescent colours. They also do this to ward off rival males,” said Mr Tea. “In a reef where multiple species often occur, there is increased pressure for males to attract not only a female’s attention, but also the female of the correct species.”

“We have only just begun scratching the surface of this exciting group, and more work still needs to be done in order to fully understand the drivers of species diversification,” he continued.

That work, and the present study, might be germane to reef conservation and management, too. For example, the finless ‘mutant wrasse’, an Australian endemic species restricted to a narrow distribution of reefs in far northwest Western Australia, is listed as vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of threatened species. The species has been placed in its own genus, with a single species. However, Mr Tea’s study finds strong evidence that this species is simply a derived fairy wrasse, and that its loss of fins likely resulted from it being ‘bottlenecked’ in a narrow area.

Fairy wrasse facts

- Today, there are 61 fairy wrasse species, with new species continually being discovered.

- Fairy wrasses are petite – they grow no larger than 15cm in length.

- They live in large groups in rubble reefs (dead coral and rocks), next to coral cover, at depths of 10 to 250 metres.

- Males are more colourful, larger, and often sport more ornamented fins than females (this is known as ‘sexual dimorphism’).

- Fairy wrasses are sequential hermaphrodites, meaning that females are capable of changing into fully functional males.

- Fairy wrasses were discovered in the mid-1800s, yet scientists only began to investigate their origins and evolutionary relationships in the last few decades.

Declaration: Yi-Kai Tea was funded by a Research Training Program Scholarship from the Australian Government and by an Australian Museum Research Institute Postgraduate Award. Nathan Lo and Simon Ho were funded by the Australian Research Council (FT160100463 and FT160100167). Peter Cowman was funded by an ARC DECRA Fellowship (DE170100516) and the ARC Centre of Excellence Program (CE140100020).